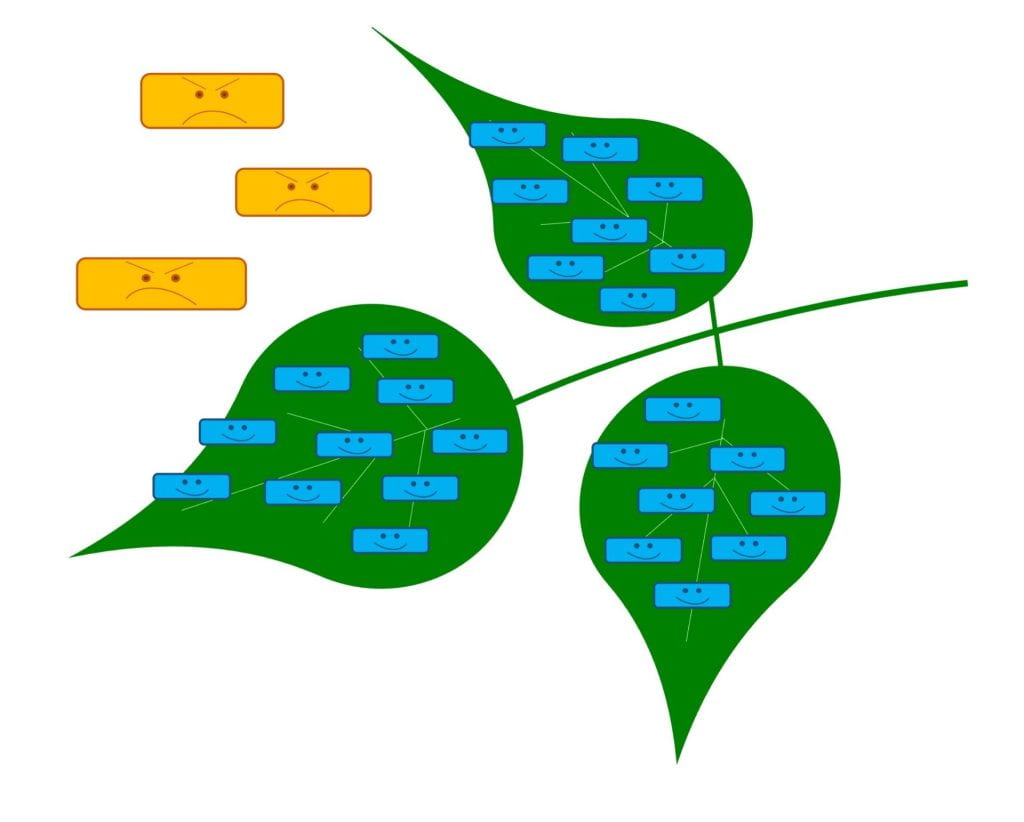

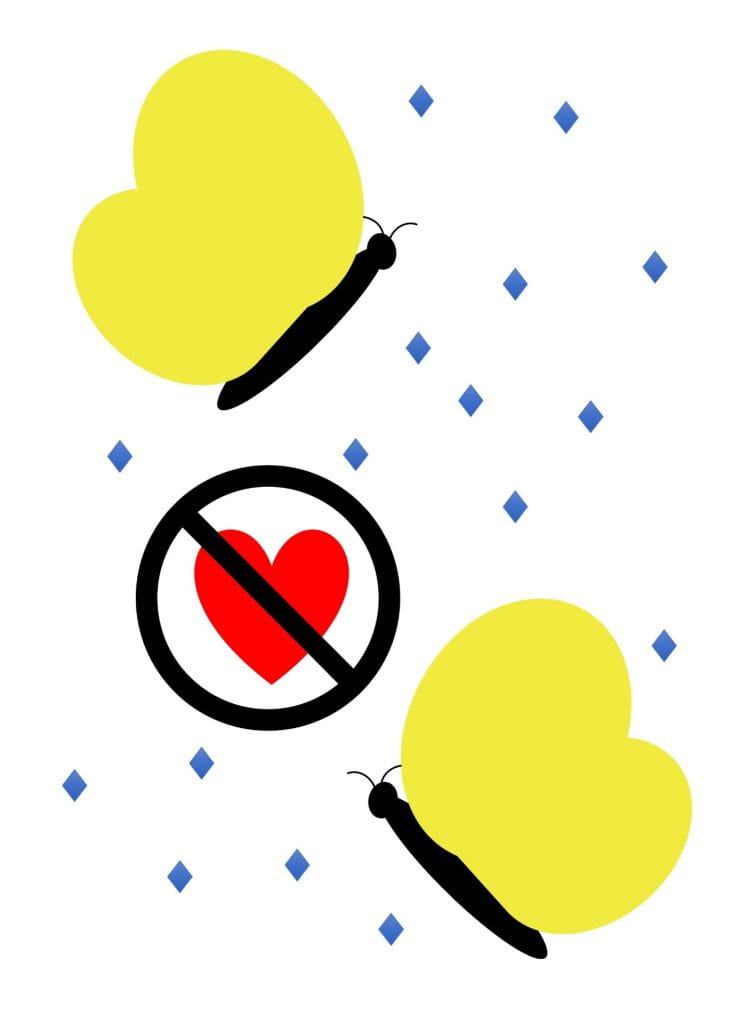

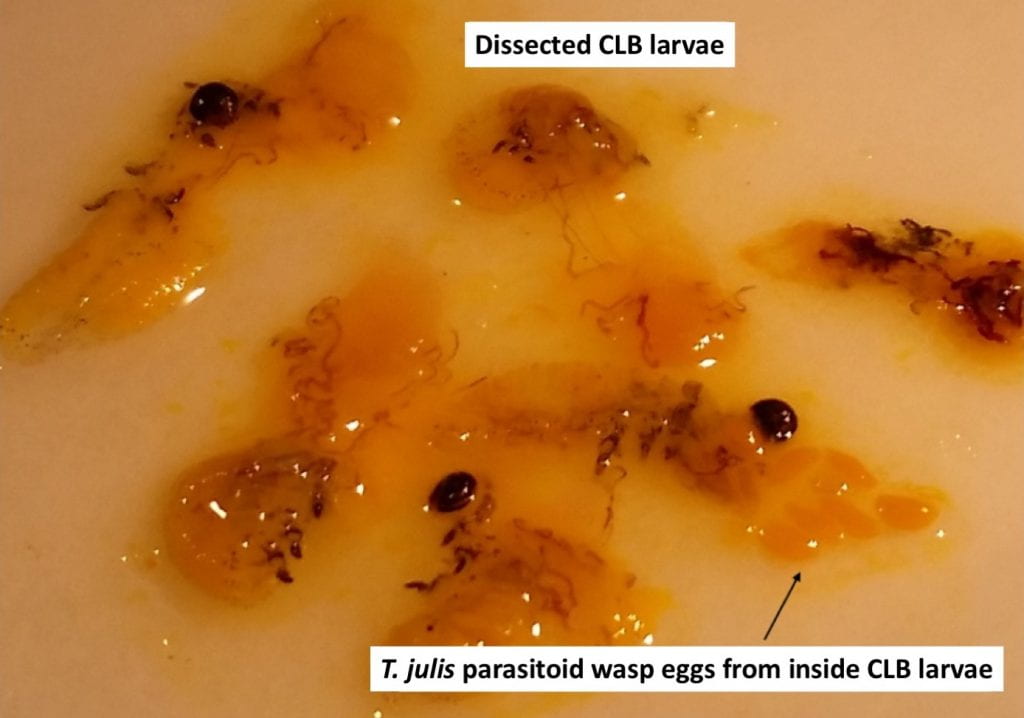

Hopefully we can all agree that protecting friendly insects (pollinators and natural enemies of pests) on our farms and in our gardens and landscapes is important. We want to manage pests, without hurting bees, butterflies, ladybugs, parasitoid wasps, minute pirate bugs, hover flies, ground beetles, and so many more of our insect friends. Using IPM tools other than pesticides is a great way to do this. When it is necessary to use pesticides as an IPM tool, how do you choose a pesticide – whether it is organic, conventional, or biological – that poses the least risk?

Practices that help reduce risk to beneficial insects

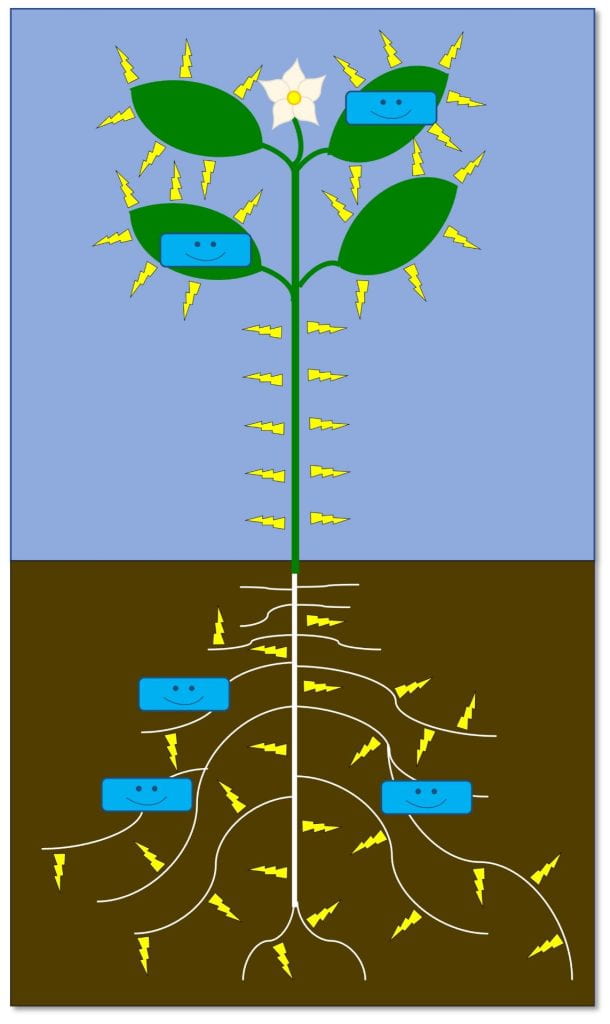

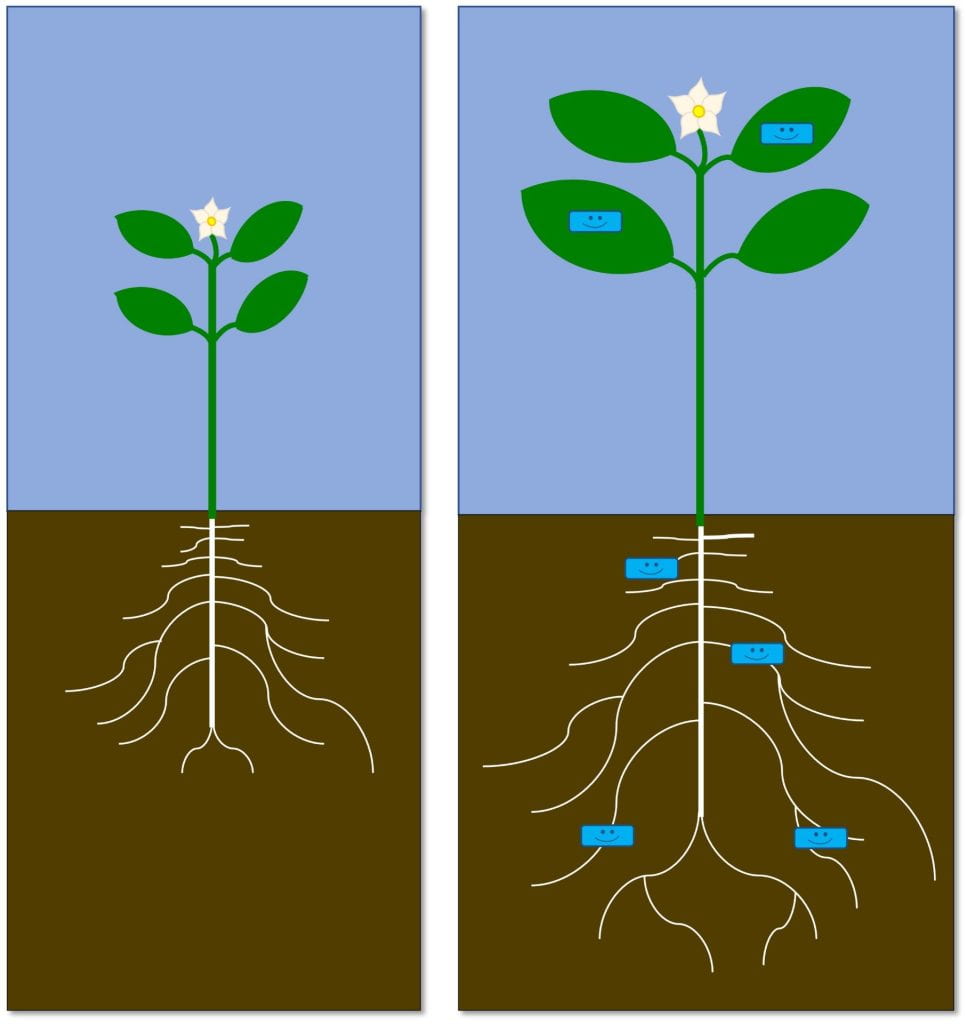

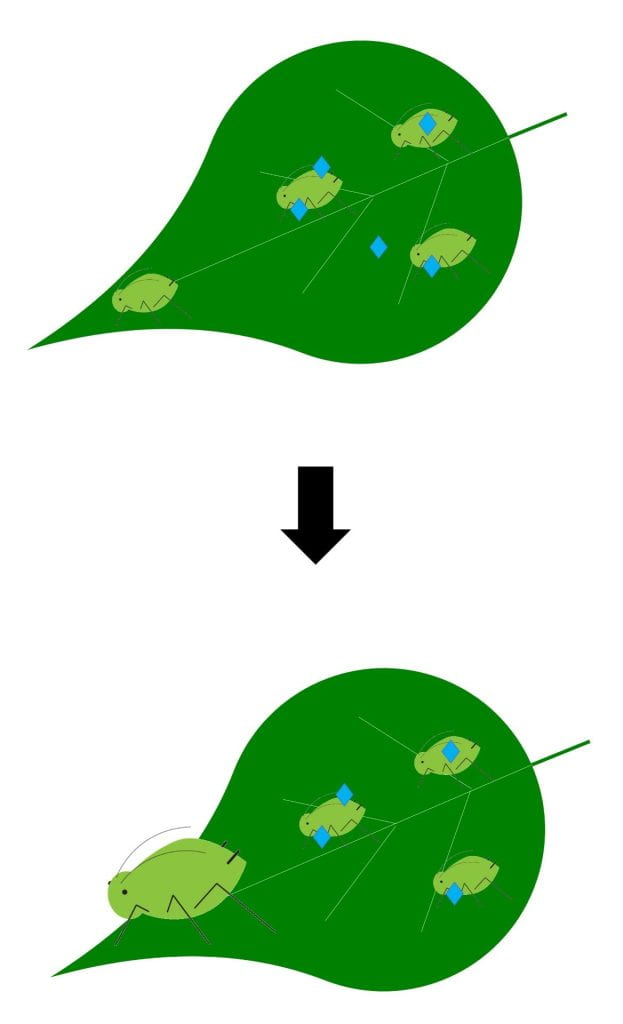

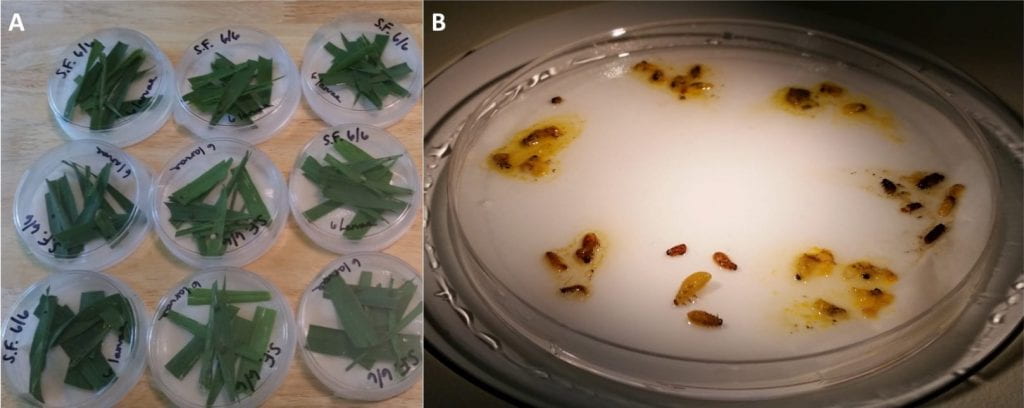

No matter how hazardous or toxic any substance is, insects are only at risk if they are exposed to that substance. By using integrated pest management practices like crop rotation, sanitation, and scouting for pests, you can reduce the number of pesticide applications needed to manage pests. Making fewer pesticide applications is a great way to start protecting beneficial insects. Some pesticides are particularly dangerous to insects because they linger so long in the environment after they are applied (have a long residual), posing a greater risk. Other pesticides quickly break down in the environment after being applied to plants, so they pose less risk.

Being careful about when you apply a pesticide can also reduce the likelihood that a beneficial insect will be exposed to it. Bees are less active at certain times of day (especially early morning and evening). However, some wild bee species forage at different times of day. For example, squash bees are early risers, and can be found visiting squash, pumpkin, and cucumber flowers before honey or bumble bees are active. Check the area where you plan to apply a pesticide, and pick a different time if bees are present. Some pesticide labels require that you do not apply that product while bees are foraging. Some pesticides will still harm bees that visit a flower some time after the pesticide is applied. Avoiding pesticide applications when plants are flowering will provide additional protection to beneficial insects, but may not be practical on all crops.

Where you apply pesticides also matters. Have you planted some habitat for beneficial insects? Prevent pesticide spray drift into these habitats. Are there flowers blooming amongst the grass on the orchard floor? Mowing them before you spray the fruit trees overhead could make insects less likely to visit during or right after you spray.

Resources to consult

First, read the pesticide label (and follow it). The label is the law and will have instructions on how to protect pollinators and other non-target organisms when using a pesticide.

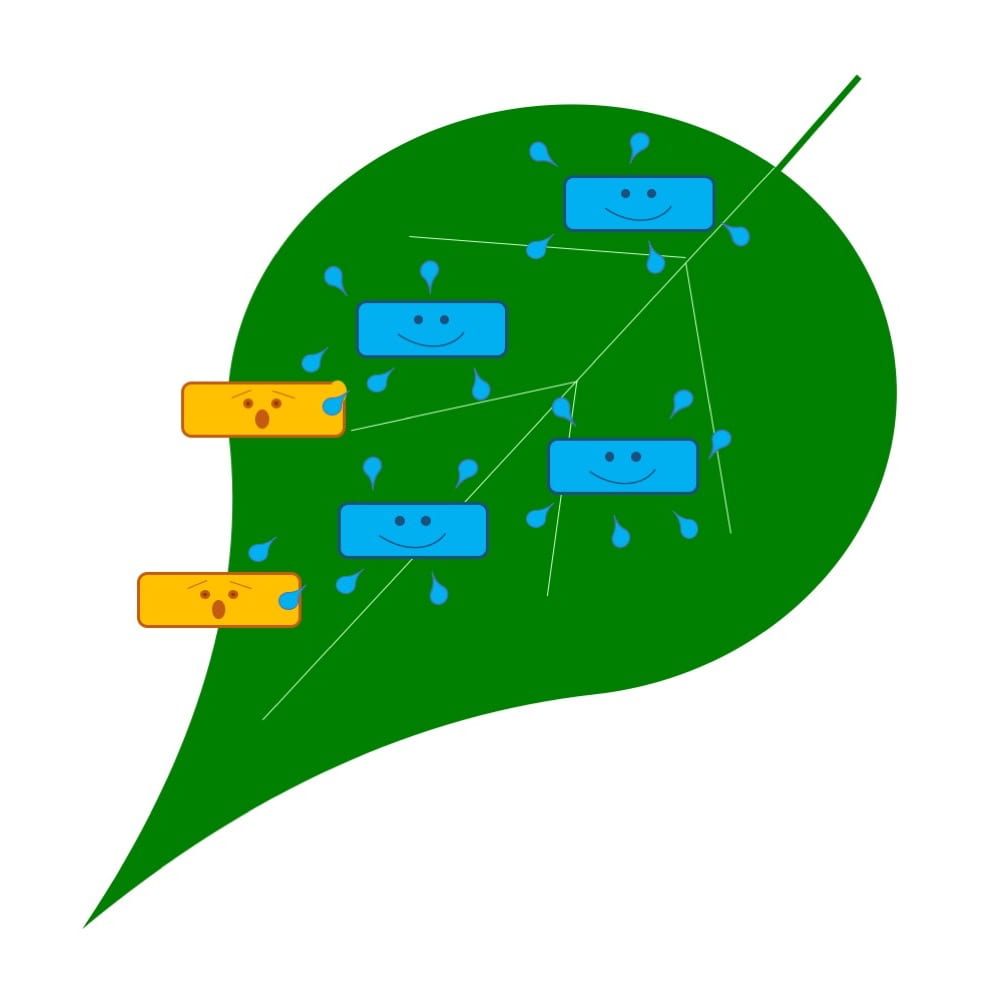

If you know the pesticides you are considering, and especially if you know the specific natural enemies you are trying to protect, you can find some good information from companies that sell beneficial insects, or pesticides. I am aware of searchable databases or charts describing pesticide compatibility from four companies that sell (mostly) arthropod and nematode natural enemies: Agrobio, Biobest, BioWorks, and Koppert.

EIQ stands for Environmental Impact Quotient. You can read more details on the NYSIPM website, but in a nutshell the EIQ quantifies the risks of pesticides. You can use the EIQ calculator on our website to compare these numbers for different pesticides at the rates you plan to use them. The higher the number, the higher the risk. There are different components to the EIQ; risks to consumers, workers, and the environment (ecological). The ecological risk includes risks to natural enemies (as well as fish, birds, and bees). The EIQ calculator will give you an overall EIQ value as well as values for each category of risk (consumers, workers, ecological). Or, you can download this spreadsheet of EIQ values for pesticides, and sort by values for bees or beneficials (columns P and Q).

The University of California IPM Program’s pesticide active ingredients database summarizes the toxicity of some pesticides (including insecticides) to natural enemies and pollinators, as well as other hazards.

The Cornell Pollinator Network produces Pollinator Protection Guides for an increasing number of crop groups to help you understand the toxicity of different pesticide active ingredients to bees.

A few pesticides to avoid

You’re using good IPM, and you still need to use an insecticide. You’re trying to choose. I used information I collected from a few different sources (listed at the end of this post) to categorize some insecticides as “most” or “moderately” harmful. These are not exhaustive lists.

Most harmful to beneficial insects:

- Carbaryl – active ingredient found in some products called Sevin

- Neonicotinoids – active ingredients include imidacloprid, acetamiprid, thiamethoxam and may be found in such products as Admire, Assail, and Actara; In NY many products with these active ingredients are now classified as restricted use, so only certified pesticide applicators are allowed to buy or use them.

- Natural pyrethrins – PyGanic is one product with this active ingredient; similar to synthetic pyrethroids, but this active ingredient degrades quickly in the environment (short residual)

- Synthetic pyrethroids – active ingredients include bifenthrin, cypermethrin, lambda-cyhalothrin, permethrin, and others; can be found in products called Sevin, Eight, Warrior, and others; similar to natural pyrethrins, but last much longer in the environment (long residual)

- Spinetoram – Radiant is one product that contains this active ingredient; a synthetic version of spinosad, but more toxic to beneficial insects than spinosad

Moderately harmful to beneficial insects:

- Azadirachtin – active ingredient found in products such as Aza-Direct, Azaguard, Neemix

- Bifenazate – active ingredient found in products such as Acramite

- Chlorantraniliprole – active ingredient found in Coragen; among natural enemies, parasitoid wasps are probably most at risk. There may be some synergistic effects on bees when combined with other pesticides (see Cornell Pollinator Protection Guides)

- Indoxacarb – active ingredient found in products such as Avaunt

- Insecticidal soaps – active ingredient is potassium salts of fatty acids and can be found in M-Pede and many other products; most harmful to soft-bodied insects (including predatory mites), while beetles may be less susceptible

- Spinosad – active ingredient in Entrust; similar to spinetoram, but it is the natural version of this chemical; not as toxic to beneficial insects as spinetoram

So what are the alternatives?

Remember that pesticides, by definition, are toxic to some living things; that’s why they kill and repel pests. There is no such thing as a completely safe pesticide. But here are a few insecticides that are gentlest on beneficial insects. And let me reiterate: Reducing the use of pesticides through good IPM is the best way to protect insects from pesticides.

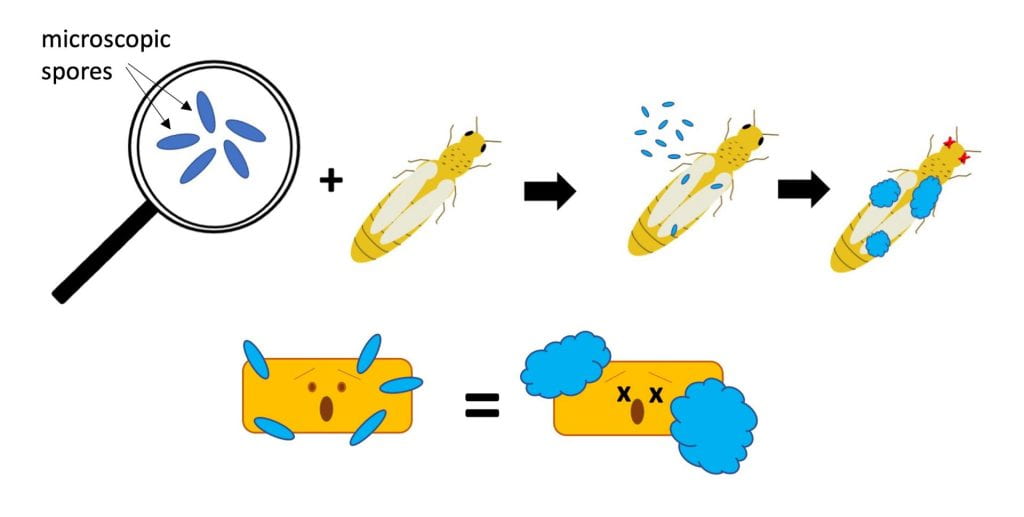

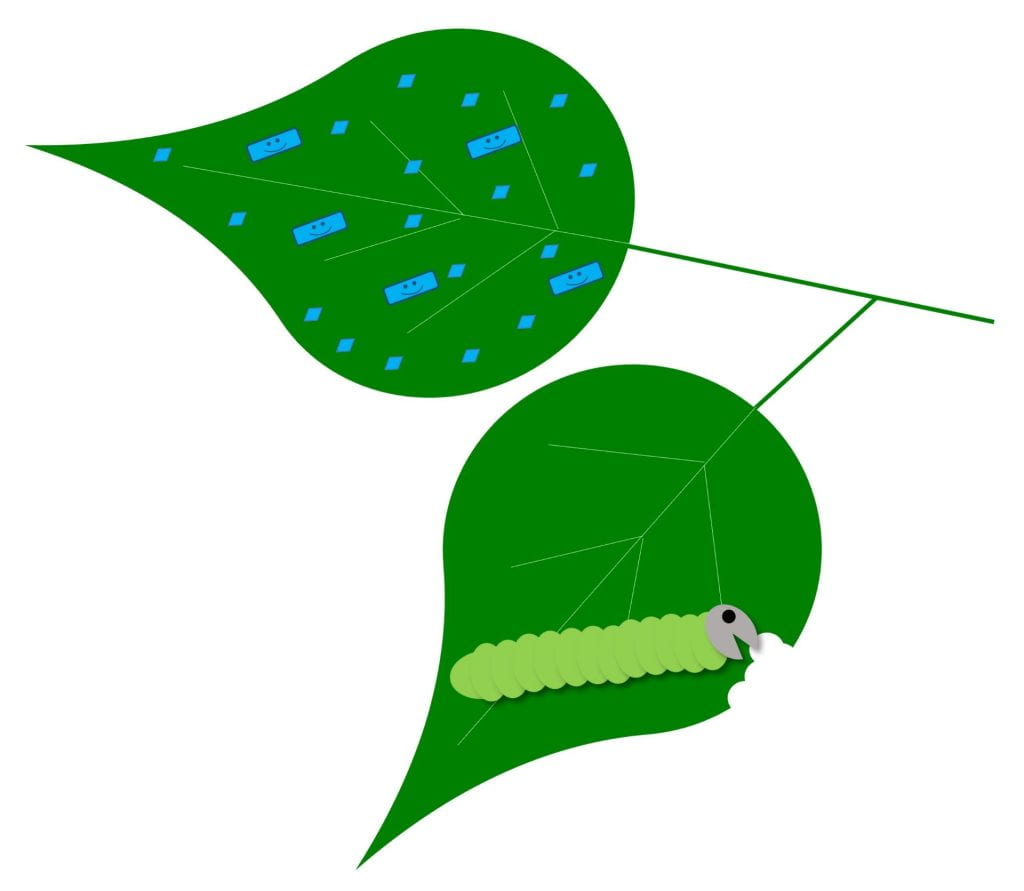

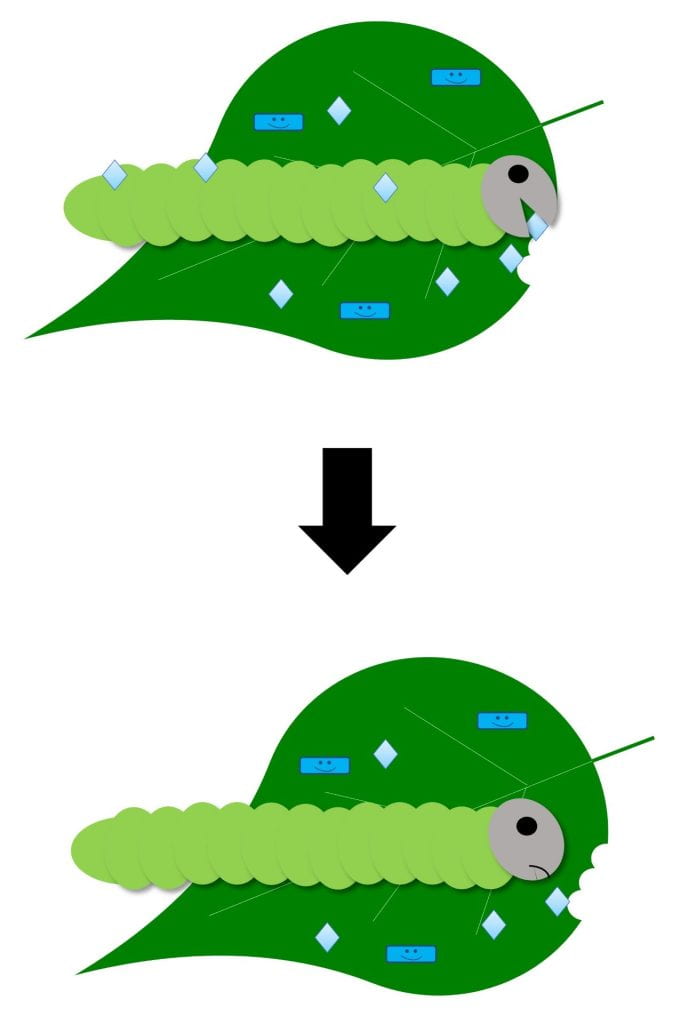

- Beauveria bassiana – several strains of this fungus are active ingredients in different insecticides, including BotaniGard

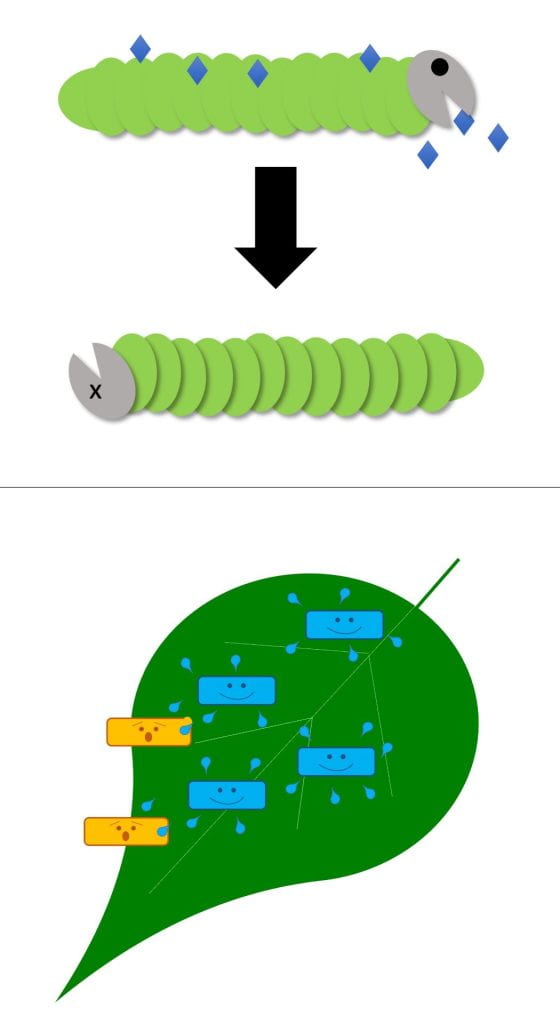

- Bt or Bacillus thuringiensis – bacterial active ingredient in pesticides such as Agree, Dipel, and others; quite specific to the insect groups specified on the label; different subspecies are effective against different groups of insects

- Flonicamid – active ingredient in Beleaf

- Horticultural oils – there are many different active ingredients that fall in this group; may be more toxic to bees than to natural enemies, but require direct contact with the insect

- Cordyceps (formerly Isaria or Paecilomyces) fumosorosea – another fungal active ingredient found in products such as PFR-97

- Clarified hydrophobic neem oil – Note that “whole” neem oil contains azadirachtin (which I listed in the “moderately harmful group”), while clarified hydrophobic neem oil does not. Azadirachtin is extracted from neem oil, leaving the clarified hydrophobic neem oil behind.

A few reminders…

- Remember that the information in this post is not a substitute for a pesticide label. The label is the law, and you must read and follow the label of any pesticide you are using. Laws and labels change. It is your responsibility to use pesticides legally. Trade or company names used here are for convenience and information only; no endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

- For questions about pesticide use, regulations, and safety, contact the Cornell Cooperative Extension Pesticide Safety Education Program. If you live in New York State, you can find labels for pesticides that are registered in NY at the DEC’s NYSPAD website.

- Just because a pesticide isn’t on the “most” or “moderately” harmful lists above, does not mean it is harmless to insects. These lists are not exhaustive, and for some products insufficient information exists.

Sources consulted:

- Pesticide compatibility checkers from two companies that sell arthropod biocontrol agents: Koppert and Biobest

- Pesticide active ingredients database from the University of California IPM Program

- A nice explanation of how insecticidal soaps work from Kansas State University

- Pollinator Protection Guides from the Cornell Pollinator Network – look up information about the toxicity of different pesticides to bees

- The National Pesticide Information Center has great information about many pesticide active ingredients, including this one on neem oil.

- Environmental Impact Quotient (EIQ) calculator and spreadsheet from NYSIPM

- Succinct explanation of the difference between pyrethrins and pyrethroids from Mississippi State University Extension

This post was written by Amara Dunn, Biocontrol Specialist with the NYSIPM program. Special thanks to Diana Obregon Corredor for providing review and input.

This work is supported by NYS Departments of Environmental Conservation and Agriculture and Markets.