Last summer I wrote about integrated pest management strategies (IPM) for tomato bacterial diseases and how biopesticides fit into strategies for managing these diseases. You’ll recall that research trials conducted at Cornell in Chris Smart’s lab indicated that you could replace some copper sprays with the biopesticides Double Nickel or LifeGard and achieve the same level of control of tomato bacterial diseases. In 2023, we wanted to demonstrate what this might look like on vegetable farms around New York State – Long Island, eastern NY, and western NY. Here’s what we observed.

Results from On-Farm Demos

Biopesticides are not a panacea for tomato bacterial disease problems. When disease pressure is severe and weather is favorable, bacterial diseases can be difficult to manage, even with copper-based fungicides. Canker is especially difficult to manage because the bacteria that cause the disease move systemically within the plant. Successful management of bacterial diseases in tomatoes requires the use of multiple IPM tools, including starting with clean seed and healthy transplants, and using new (or effectively disinfected) tomato stakes.

On farms that experienced tomato bacterial disease outbreaks, adding Double Nickel did not satisfactorily control bacterial disease. These farms had very uneven distribution of tomato bacterial canker across the fields, complicating comparisons between the Double Nickel alt. copper treatments and the copper only treatments. Two farms (in western NY) saw slight to moderate increases in fruit quality when they added Double Nickel sprays in between copper applications compared to applying copper every 10-14 days. This resulted in estimated 2% and 37% increases in fruit value, corresponding to an extra $19 (from nine harvests) or $72 (from four harvests) from 100 row feet of tomatoes. However, the Double Nickel sprays were in addition to copper sprays, not replacing them. We don’t know if applying copper every 7-10 days would have resulted in better disease control. On the third farm, we saw no benefit of replacing half of the copper applications with Double Nickel.

The two cooperating Long Island farms saw no bacterial disease in 2023. But replacing half of the copper applications with either Double Nickel or LifeGard still seemed to have economic advantages. We estimate that the value of their crops increased by 7% and 59%, or $244 and $1,617 per 100 row feet of tomatoes harvested four times. Note that the price for fresh tomatoes on Long Island is high compared to some other markets in NY. We used $5-$6/lb in our Long Island estimates. Also, we don’t know what would have happened if there had been a bacterial disease outbreak on these farms.

On all cooperating farms, we collected data on very small sections of the field (10-40 row feet of tomatoes). Estimated potential impacts on yield over much larger areas should be taken with a grain of salt.

Economics

We researched some prices for pesticides from a few different suppliers. Below are the assumptions we made to calculate some price estimates and make comparisons among some biopesticides and copper pesticides. Prices for pesticides can vary across regions and time. If you think any of these numbers are far out of line, please let Amara know!

| If you are applying… | and a container costs you… | and you apply at a rate of… | Your cost per A per application is: |

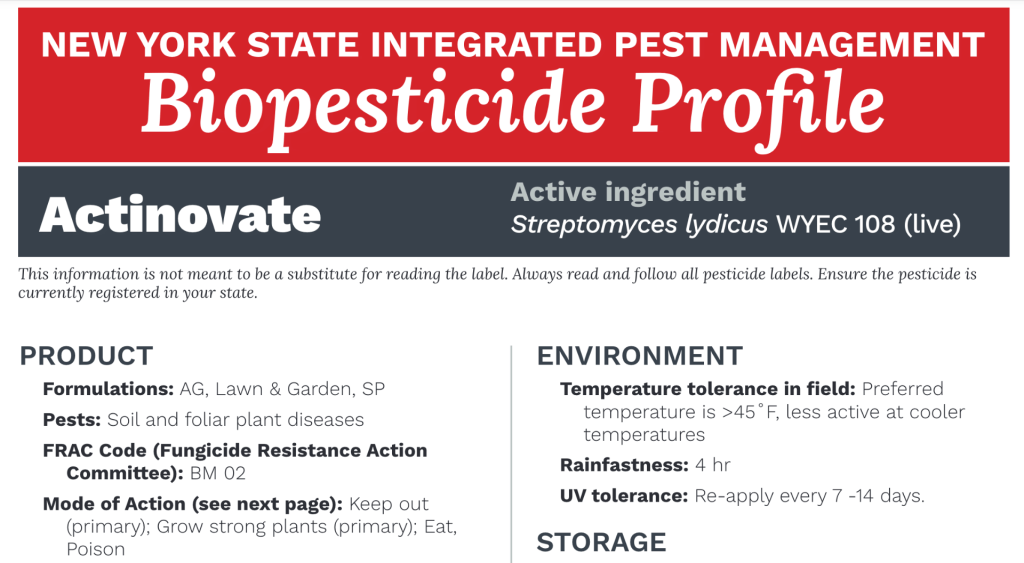

| Actinovate AG | $115/18 oz bag | 7.5 oz/A (range on label is 3-12 oz) | $48.00 |

| Double Nickel LC | $85.25/1 gal | 1 qt/A (recommended for tomato bacterial diseases) | $21.31 |

| LifeGard WG | $148/1 lb bag | 4.5 oz/100 gal and 50 gal/A = 2.25 oz/A | $20.80 |

| copper (Kocide 3000-O or Badge X2) | $102/10 lb bag | 1.25 lb Kocide, 1.8 lb Badge X2 (highest rate on label) | $15.00 |

| copper (Badge SC) | $150/2.5 gal | 1.8 pt/A (highest rate on label) | $13.58 |

| Copper (Champ Formula 2 Flowable) | $139.95/2.5 gal | 1.33 pt/A | $9.31 |

| copper (Cueva) | $114/2.5 gal | 1 gal/A (label rate is 0.5-2 gal) | $46.27 |

As you can see, the biopesticides in the table range from fairly similar in price (Double Nickel and LifeGard) to approximately 5 times the cost of the less expensive coppers (Actinovate). Each copper application replaced with either Double Nickel or LifeGard is estimated to increase the pesticide cost by $6-$12 per acre per application. If a grower makes eight applications in a season to protect tomatoes from bacterial diseases, this would be an increase of $24-$48 per acre for the season if half of the copper applications are replaced with Double Nickel or LifeGard. If a grower adds LifeGard or Double Nickel applications to a 14-day copper spray program, the cost increase is greater. Purchasing product for four additional applications costs an extra $84 per acre, not including other costs of making more applications, like fuel, labor, equipment depreciation, etc.

Protecting people and the environment

Replacing some copper sprays with biopesticides can have other benefits. For example, the following table compares restricted entry intervals (REIs), label signal words, and field use ecological Environmental Impact Quotient (EIQ) for several biopesticides and copper formulations. Shorter REIs indicate a pesticide has lower toxicity to agricultural workers. The signal word shows the relative acute toxicity of the pesticide to the pesticide applicator.

| Product | Active Ingredient (%) | Rate | REI | Signal word | Field Use Ecological EIQ1 |

| Actinovate AG | Streptomyces lydicus WYEC 108 (0.037%) | 12 oz/A | 4 hrs | Caution | NA |

| Double Nickel LC | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain D747 (98.85%) | 1 qt/A | 4 hrs | none on label | NA |

| LifeGard WG | Bacillus mycoides isolate J (40%) | 4.5 oz/A | 4 hrs | Caution | NA |

| Serenade Opti2 | Bacillus subtilis QST 713 (26.2%) | 20 oz/A | 4 hrs | Caution | 7.2 |

| Badge SC | copper hydroxide (15.36%); copper oxychloride (16.81%)3 | 1.8 pt/A | 48 hrs | Caution | 40.1 |

| Champ Formula 2 Flowable | copper hydroxide (37.5%) | 1.33 pt/A | 48 hrs | Warning | 34.5 |

| Cueva | copper octanoate (10%) | 2 gal/A | 4 hrs | Caution | NA |

| Kocide 3000-O | copper hydroxide (46.1%) | 1.25 lb/A | 48 hrs | Caution | 38.2 |

| MasterCop | copper sulfate pentahydrate (21.46%) | 2 pt/A | 48 hrs | Danger | 66.4 |

1 The Environmental Impact Quotient (EIQ) seeks to quantify the environmental impacts of pesticides. Higher numbers indicate more negative impacts. The values reported here are “field use” values, calculated based on the rates listed in the table. These values vary depending on how much product you use per acre. The ecological component summarizes risk to fish, birds, bees, and beneficial insects.

2 The active ingredient in Serenade Opti is in the EIQ database, while the active ingredients of the other biopesticides in this table are not. The EIQ for Serenade Opti is expected to be similar to those of Double Nickel and LifeGard because they have similar active ingredients. It may also be similar to the EIQ for Actinovate.

3 Only copper hydroxide – not copper oxychloride – was in the EIQ database, so this ecological EIQ was calculated using 32.17% copper hydroxide (sum of the percentages of the two active ingredients).

Other benefits of reducing copper applications on a farm could include:

- It reduces the risk of selecting for tomato bacterial pathogens that are resistant to copper.

- Many copper fungicides leave a visible residue on fruit, which may impact marketability if applied close to harvest.

Update on labels

In last summer’s post we noted that neither Double Nickel nor LifeGard included tomato bacterial canker on their labels. In New York State, formulations of these biopesticides now have 2(ee) labels that include this disease on tomatoes. Make sure you have a copy of both the original label and the 2(ee) label in your possession if you are using these products for tomato bacterial canker in NY. If you are in NY, you can find these and other labels through NYSPAD.

The Bottom Line

- It is very important to use all your IPM tools for tomato bacterial disease management, especially for canker. If you are bringing canker to your field in seedlings or on tomato stakes, it will be very difficult to catch up with the disease using any pesticide if weather conditions favor disease.

- Some biopesticides are competitively priced (per bottle and per acre) with copper formulations. Replacing a few copper applications with these products will not cost you much more.

- Replacing some copper applications with biopesticides offers some additional benefits, including copper resistance management, and potentially reduced risk to the environment and human health.

Changes in pesticide registrations occur constantly and human errors are possible. Read the label before applying any pesticide. The label is the law. No endorsement of companies is made or implied.

This post was written by Amara Dunn-Silver, Biocontrol Specialist with the NYSIPM program. Thanks to collaborators Chris Smart, Professor in the School of Integrative Plant Science, Plant Pathology and Plant-Microbe Biology Section at Cornell University, Crystal Stewart-Courtens, Extension Vegetable Specialist, Eastern NY Commercial Horticulture Program; Elizabeth Buck, Cornell Vegetable Program; Margaret McGrath, Retired Faculty, School of Integrative Plant Science, Plant Pathology and Plant-Microbe Biology Section at Cornell University, and Sandra Menasha, Cornell Cooperative Extension, Suffolk County. Support for this project was provided by the NY Farm Viability Institute.