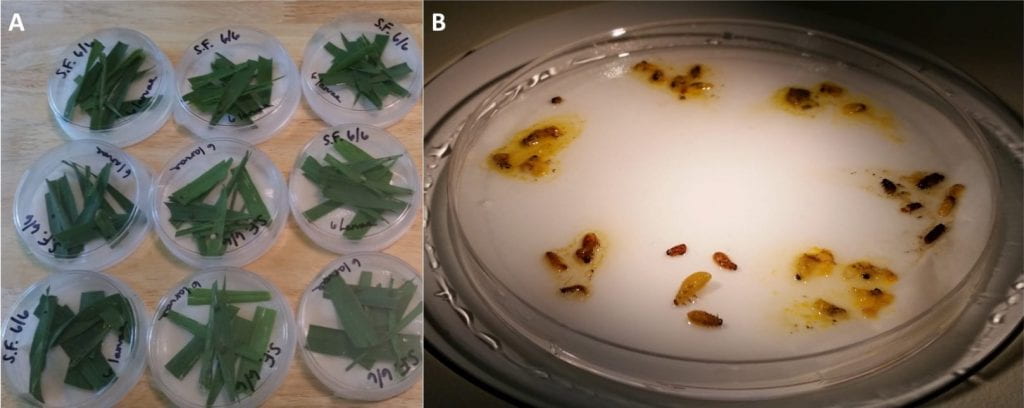

Recall from this post that I’m creating habitat for beneficial arthropods (including insects, spiders, predatory mites, etc.) around my house this spring. Because more of us may be doing this while we’re staying home to keep each other safe, I’m sharing my experiences here (as well as on Twitter and Instagram). The previous post covered site selection. Today I will talk about the species I’ve chosen (and why).

What I’m planting in my yard

The front and side yards get plenty of sun (because they face south and west), so I’m looking for plants that thrive in full sun. And I’ll admit that I’m interested in more than just supporting beneficial arthropods. I also want my front and side yards to look reasonably nice. (I don’t want to make enemies of my new neighbors!) And I want to grow flowers for cutting. So I am not sticking strictly to native plant species or to perennials. Some plants I picked just because I thought they looked nice. For example, I was beguiled by ‘Chim Chiminee’ Rudbeckia. The pollen and nectar produced by the native species may have been bred out of this variety. I’ll find out. I also just love ‘Persian Carpet’ zinnias.

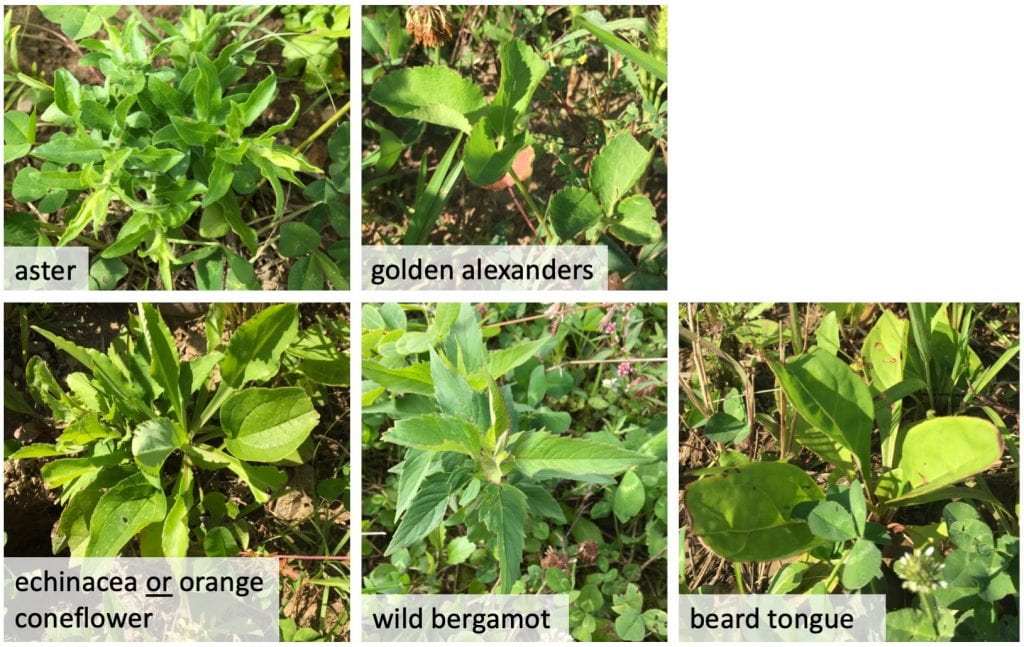

I’ve started a lot of plants from seeds I had in my fridge (e.g., snap dragons, echinacea, bachelor’s buttons). Others I will direct-seed outside (e.g., sunflowers, zinnia, cosmos), and I may also purchase some transplants from local nurseries (many have great strategies for safe curbside pick-up!).

Choosing plants for beneficial arthropods – the basics

Which plant species to grow to support beneficial arthropods (whether it’s pollinators or natural enemies of pests, or both) is a common question. The answer is both straight-forward, and also complicated. In addition to shelter and protection from pesticides, all beneficial arthropods need something to eat. In general, plants that provide plenty of nectar and pollen help to provide this food. Many natural enemies of pests will also eat pollen or nectar (e.g., at certain life stages, or as a supplement to the pests they eat). Even if they don’t, the pollen and nectar will often attract small arthropods that natural enemies can feed on. So, the simple answer is that a plant that produces lots of pollen and nectar, will thrive in the setting where you want to plant it, and is not invasive is a good choice for supporting beneficial arthropods. Plants that are marketed as supporting pollinators are easy to find and are likely to also support natural enemies.

But, of course, it’s not exactly that simple…

Choosing plants – natives, cultivars, and more

Many people ask if they should only grow native plant species, or if it’s ok to plant cultivated varieties of native species, or non-native species. (Hopefully it’s obvious that you should never plant an invasive species in your yard!) Annie White at the University of Vermont wrote a 254-page dissertation on the topic. These two sentences from her abstract summarize her findings nicely: “Our study shows that many insect pollinators prefer to forage on native species over cultivated varieties of the native species, but not always, and not exclusively. Some native cultivars may be comparable substitutions for native species in pollinator habitat restoration projects, but all cultivars should be evaluated on an individual basis.” You might also want to take a look at this article from the University of Maryland and this one from the Xerces Society. In summary, I would say it’s up to you whether you want to plant exclusively native species, or not.

According to David Smitley from Michigan State University, perennials are usually better choices for bees than annuals, but this article includes a list of annuals that are attractive to bees. Alyssum is an annual that definitely supports natural enemies, but many of the other annuals on this list may also support natural enemies.

Choosing plants – attracting specific arthropods

If you are trying to attract very specific natural enemies (e.g., parasitoid wasps, lady beetles) your plant choice can also get more complicated. Some great work has been done by researchers at Michigan State University documenting which arthropods (pollinators, natural enemies, and some pests) visited different plant species native to Michigan. They also offer a simplified summary. “Habitat Planning for Beneficial Insects” from the Xerces Society includes notes in the charts at the end about which beneficial insects are particularly attracted to the species listed. This resource from Oregon State University describes some specific plants and the arthropods they support. Finally, although this study was conducted in the United Kingdom, there might be some relevance to the Northeast U.S.

Update: During Summer 2020 (while I was doing less field work), I reviewed the literature I could find on the value of specific plants for specific natural enemies. Here is the spreadsheet I compiled.

Lists and searchable databases

In addition to the resources already listed, you may find the following helpful in selecting plants:

- Regional plant lists from the Xerces Society

- Regional plant lists from the Pollinator Partnership

- Searchable database (including location and many plant characteristics)

- Fact sheet on pollinator plants for Northern New England from the University of New Hampshire

- List of shrubs and trees that support bees from the University of Kentucky (double-check that they will grow well here in NY!)

- List of native plants and the animals (including butterflies and bees) that they support from the University of Massachusetts

- List of plants that attract butterflies from the Michigan State University

- List of native plants that support butterflies and moths, searchable by zip code

- List of native plants for the Finger Lakes

If you want to focus on native plants, there are many organizations committed to supporting local native plants…too many to list here, but some online searching may turn up an organization that is local for you.

My current plant list

This table lists what I either have already seeded (inside or outside), or am planning to direct seed outside when it gets a little warmer. In addition to the common, scientific, and cultivar name of each plant and whether it is a perennial or an annual in NY, I also included information about why I chose it. I only marked plants as supporting bees or natural enemies if I could find documentation of that fact in the resources above. It may be that more of the plants on this list support beneficial arthropods. If you have additional information on these plants, please let me know! In some cases (for example, zinnia) the species is reported to support beneficial arthropods, but I don’t know if the cultivars I’m growing will. In many cases, the decorative value of the plant was a big part of why I chose it. The arnica? Well, I just saw that in a seed catalog this winter and ordered some on a whim.

| Common name | Scientific name | Cultivar | Annual or Perennial in NY | Bees | Natural enemies | Decorative |

| Arnica | Arnica chamissonis | perennial | ||||

| Bachelor’s buttons | Centaurea cyanus | annual | X | X | ||

| Blanketflower | Gaillardia aristata | Burgundy | perennial | X | X | X |

| Blue vervain | Verbena hastata | perennial | X | |||

| Calendula | Calendula officinalis | Remembrance Mix | annual | X | X | |

| Celosia | Celosia argentea cristata | Red Flame | annual | X | X | |

| Cosmos | Cosmos bipnnatus | Dwarf Sensation | annual | X | X | X |

| Echinacea | Echinacea purpurea | perennial | X | X | ||

| Marigold | Tagetes erecta | Senate House | annual | X | X | |

| Poppy | Papaver somniferum | Frilled White Poppy | annual | maybe | X | |

| Poppy | Papaver sp. | seed saved by a colleague | annual | maybe | X | |

| Pyrethrum daisy | Chrysanthemum cocineum | perennial | X | |||

| Rudbeckia | Rudbeckia hirta | Chim chiminee | perennial | maybe | X | |

| Snap dragon | Antirrhinum majus | annual | X | X | ||

| Strawflower | Xerochrysum bracteatum | annual | X | |||

| Sunflower | Helianthus anus | Mammoth Greystripe | annual | X | probably | X |

| Sunflower | Helianthus anus | Evening Sun | annual | X | probably | X |

| Sunflower | Helianthus anus | Sonja Dwarf | annual | X | probably | X |

| Zinnia | Zinnia elegans | Queen Lime with Blush | annual | maybe | X | |

| Zinnia | Zinnia elegans | Candy Cane Mix | annual | maybe | X | |

| Zinnia | Zinnia elegans | Benary’s Wine | annual | maybe | X | |

| Mexican zinnia | Zinnia haageana | Persian Carpet | annual | maybe | X |

This post was written by Amara Dunn, Biocontrol Specialist with the NYSIPM program. All images are hers, unless otherwise noted.

This work is supported by:

- Crop Protection and Pest Management -Extension Implementation Program Area grant no. 2017-70006-27142/project accession no. 1014000, from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

- New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets

- Towards Sustainability Foundation