Are you using copper to protect your tomatoes from bacterial diseases? Research from Cornell suggests that you could replace some of those copper applications with a biopesticide.

Preventing bacterial diseases on your tomatoes starts with good integrated pest management practices.

- > 3-year rotation out of tomatoes and peppers

- Clean seed or disease-free transplants

- Heat treat seed (unless it is pelleted or treated)

- Good sanitation in transplant production facility (e.g., new flats or sanitize between uses, sanitize greenhouse after each season)

- Inspect transplants and destroy any with symptoms of bacterial disease

- Do not work in tomatoes (e.g., tie, prune) when leaves are wet

- Either sanitize tomato stakes between growing seasons, or use new stakes each year (preferred)

- If you have an outbreak, till in plant debris quickly.

If you are doing all of these things and still need some extra protection from bacterial diseases (e.g., in a wet growing season), pesticides might also be in your IPM toolbox.

In New York, we’re fortunate that so far few bacterial isolates have been found to be resistant to copper. Copper resistance is a major problem in the southern U.S. and we’d certainly like to preserve its efficacy here in NY. Some people are also understandably concerned about the environmental impacts of using a lot of copper on their farms.

Cornell vegetable research programs led by Chris Smart and Meg McGrath have been testing products against our three bacterial diseases – spot (Xanthomonas), speck (Pseudomonas) and canker (Clavibacter) for a number of years. So far, two products – Double Nickel LC (1 qt/A recommended) and LifeGard (4.5 oz/100 gal water) – have been rising to the top. When comparing these products alone to alternating either with copper, both worked better as replacements for some copper sprays than alone. Some research trials only included the biopesticide by itself, but the Double Nickel label states that it should be applied only tank mixed or rotated with copper-based fungicides.

Double Nickel alone (one year of data in Geneva) was as good as copper against bacterial spot. Double Nickel alone (two years of data in Geneva) and LifeGard alternated with copper (one year on Long Island) were as good as copper against bacterial speck. While neither product is registered (legal) for use against tomato canker, in research trials in Geneva, Double Nickel (one year) and LifeGard (two years) alternated with copper controlled canker as well as copper alone. So if you are replacing some copper sprays with either Double Nickel or LifeGard, you’ll likely notice some incidental bacterial canker protection, too.

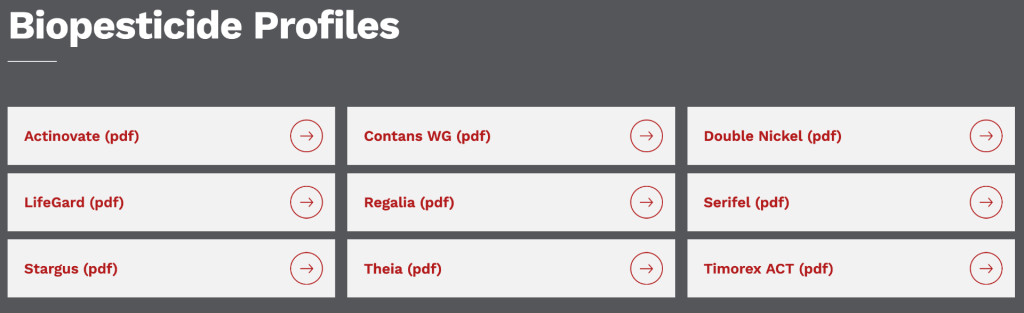

New to using biopesticides? The New York State IPM Program has a new resource to help. Biopesticide profiles (scroll to bottom of page) for Double Nickel, LifeGard, and seven other products provide information on tank mix compatibility, shelf life, and other practical tips.

Changes in pesticide registrations occur constantly and human errors are possible. Read the label before applying any pesticide. The label is the law. No endorsement of companies is made or implied.

This post was written by Amara Dunn, Biocontrol Specialist with the NYSIPM program, and Chris Smart, Professor in the School of Integrative Plant Science, Plant Pathology and Plant-Microbe Biology Section at Cornell University. Support for this project was provided by the NY Farm Viability Institute.