Hopefully you’ve been following along with a project I’m working on with Betsy Lamb and Brian Eshenaur to establish (and document the impacts of) habitat for natural enemies of pests and pollinators (collectively, beneficial insects). In December, I wrote about how the plants were growing, and in February I wrote about the time and money we’d invested in the project so far and the success of our weed management strategies. I promised an update on insect sampling, and here it is!

First of all, let me clarify that we were collecting more than just insects. Insects only have six legs. We also collected arachnids like spiders (and harvestmen), which usually have eight legs, and pillbugs, millipedes, and centipedes, which have many more than eight legs. All of these “bugs” could be correctly called arthropods. But there’s more! We also counted earthworms (which are annelids) and slugs and snails (which are mollusks). Hopefully the entomologists in my audience will pardon my use of the term “insect” to include creatures that crawl or fly but may have more (or less) than six legs throughout the rest of this post.

I described the ways that we collected insects in an earlier post. As a quick refresher:

- Pan traps catch flying insects, especially those attracted to the colors yellow and blue.

- Pitfall traps catch insects that crawl along the soil surface.

- Sweep nets catch insects that are flying or hanging out on plants.

Below is a quick reminder of our treatments. You can read all the details here. Except for Treatment H. These are “new” plots that we added in 2019. I just measured out four, 23-foot long sections of grass planted between rows of Christmas trees in the middle of the field. These row middles are mowed by the excellent Field Research Unit staff at Cornell AgriTech, where our research field is located. The grass mixture was seeded right after the Christmas trees were planted in Spring 2018, but it does include some blooming weeds from time to time (dandelions and clover, especially).

| Treatment | Description |

| A | Spring transplant, no mulch |

| B | Spring transplant with mulch |

| C | Spring direct seed |

| D | Buckwheat cover crop, then fall transplant |

| E – control | Whatever was growing there, just keep it mowed |

| F | Soil solarization, then fall direct seed |

| G | Herbicide and tillage, then fall direct seed |

| H – control | Mow seeded orchard grass mix |

And one last note before we get into the actual results. These are still preliminary results. Many, many thanks to Jason Dombroskie and Paige Muñiz for helping us with insect identification. Identification and number crunching of the data are still ongoing.

Ok, ready to see some cool insects (etc.)? Here we go!

Spiders and harvestmen

We caught a lot of spiders and harvestmen, mostly in pan and pitfall traps. What’s a harvestman? You might know it by the name daddy long legs. It looks a lot like a spider, but instead of having a distinct narrowed “waist” (actually where the two body segments of the arachnid meet), their bodies just look like single “blobs”. Both spiders and harvestmen are predators and will eat many other insects (including some pests). They may also eat nectar and pollen. Very few spiders you are likely to encounter in New York are venomous, so welcome these eight-legged biocontrol agents to your fields and gardens without fear!

We caught a lot of spiders and harvestmen, but it looks like there were fewer in the plots that were mulched at transplanting or solarized prior to seeding.

Carabid beetles

You may not notice carabid beetles (also called ground beetles) because they crawl along the surface of the soil and are usually more active at night. Also, many of them move very quickly. They are great predators of insects (and other arthropods), as well as mollusks like slugs. Some also eat seeds.

From these preliminary results, it looks like we tended to catch more carabid beetles in the fall-planted treatments (whether they were transplanted or direct-seeded). We’ll have to see if this turns out to be a consistent pattern. There were generally fewer carabids in the two control treatments.

Rove beetles

We did not catch very many rove beetles (only 55 in all of the plots for the entire summer), but like carabid beetles these predators live at the soil surface or in the soil. Some also scavenge things that are already dead or eat seeds. You can recognize them by the short wing covers (called elytra) on their backs. I think they look like mini capes.

Hover flies

Hover flies (also called syrphids) come in many shapes and sizes and get their name from the way the adults hover in the air when traveling between flowers. Many look like bees, but if they hold still long enough and you look closely, you will see that they only have two wings (bees have four), and they have very large eyes. The adults feed on pollen and nectar and are also pollinators. The larvae are predators, eating aphids, whiteflies, and scales.

We were surprised to see similarly low numbers of hover flies in the two spring transplanted plots (in which deliberately-planted wildflowers were largest and produced the most flowers) and in the mowed grass control. More hover flies were collected from the weedy control, all the direct seeded plots, and the fall transplanted plots (which had smaller wildflowers with fewer blooms). We don’t know why.

Lady beetles

Lady beetles may be the most well-recognized biocontrol agent, but they were not the most abundant one collected in our sampling. We only collected 65 larvae or adults from all plots over the entire summer. Both life stages are predators, but adults of at least some species will also eat pollen and nectar. We identified the species of each adult (but not the larvae), and a picture of each is below.

Lacewings

All lacewing larvae are predators, and the more easily recognized adults of some species are also predators. Others eat pollen as adults. We did not catch very many in our plots; only 40 all summer from all plots.

Minute pirate bugs

This may be one of my new favorite natural enemies. They are definitely minute (no more than a quarter of an inch long) but feed on small insect pests like aphids, mites, scales, and thrips, as well as pollen and nectar. We only collected 19 from all plots over the whole summer. At home, I sometimes find them running across my table after I’ve brought freshly cut flowers inside. In this video, you can see one exploring the map of a corn maze. Actually, it was looking for thrips to eat.

minute pirate bug on corn maze map

Bees

Interestingly, while we collected a lot of bees of many different kinds over the summer (at least 18 different genera), very few were the iconic honey bees or bumble bees. I have been told by a bee expert that the pan traps tend to catch bees other than honey or bumble bees, and we did set these traps about twice as often as we used sweep nets. So this may have impacted the types and numbers of bees we collected. Nevertheless, these data are a reminder that there are lots of bees out there besides the ones we’re most familiar with. I encourage you to learn more about wild bees of New York.

Butterflies

At the beginning of this post, I listed three methods we used to collect insects. Well, actually there was a fourth method, but it was used to count insects rather than to collect them. We did a Pollard Walk through each plot once a month by simply walking along the side of the plot and counting the number and type of butterflies we saw. We counted very few butterflies during these walks, but here are pictures of the species that did visit our plots (either in the adult or caterpillar life stage).

So that’s it for the beneficial insects I’m going to write about today. We also caught some not-so-beneficial insects (and mollusks).

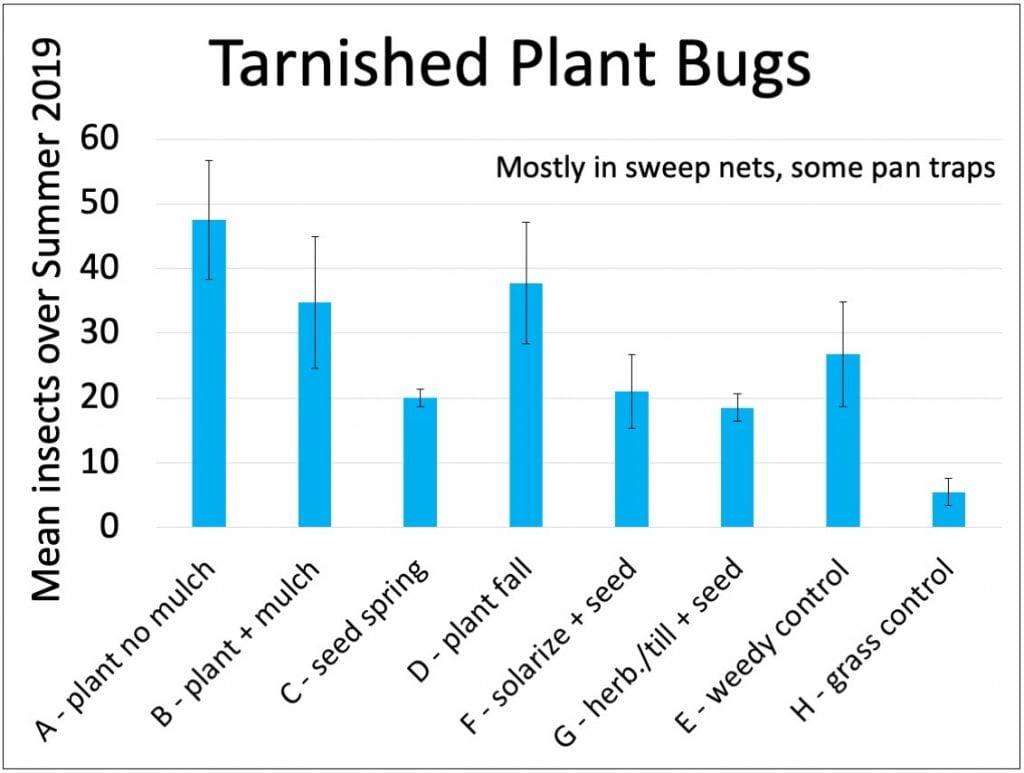

Tarnished plant bugs

These are generalist herbivores, feeding on leaves, fruits and flowers of many plants. They can be damaging pests on some fruits (like strawberries) and vegetables. In our plots, I think they caused some damage to the coreopsis flowers. We’re not too worried because they aren’t pests of Christmas trees, but we were disappointed to find the largest numbers of tarnished plant bugs in the more mature habitat plots (those started by transplanting, as opposed to direct-seeding). Other researchers also reported that planting wildflower strips adjacent to strawberries could increase tarnished plant bug populations.

Leafhoppers

Leafhoppers are another insect that we aren’t too concerned about with Christmas trees, but can be a pest of other crops. I learned that you can distinguish this group of insects by their pointy flattened (top to bottom) heads and the bristles on their back legs. The spring transplanted plots in which wildflower plants were most mature and produced the most blooms also had fewer leafhoppers than other treatments.

Slugs

As I mentioned at the beginning of this post, slugs are mollusks, not insects (or even arthropods) and they can be pests of many different crops. The picture above is definitely the largest slug that we collected during 2019. Interestingly, there seemed to be fewer slugs in the plots where we solarized the soil during the 2018 growing season. I was interested to learn that soil solarization is known to kill slug eggs, and I wonder if we’re seeing that effect here. I don’t know how far slugs move from where the eggs hatch, and it will be interesting to see if this effect persists in future years.

Believe it or not, this is not the full list of insect (or arthropod, mollusk, or annelid) groups we collected and counted. Also, I will remind you again that these data (especially the bee data) are preliminary. Although I’m sad to be unable to collect insects this summer due to COVID-19, I’m looking forward to finishing the analysis of the 2019 data and getting ready to hopefully collect insects again in 2021. In the meantime, you can see pictures of what’s happening in these plots throughout the summer on my Twitter and Instagram accounts. And I will write at least one more post about this project later this year.

This post was written by Amara Dunn. All pictures or videos were taken by her, unless otherwise credited.

This work is supported by:

- Crop Protection and Pest Management -Extension Implementation Program Area grant no. 2017-70006-27142/project accession no. 1014000, from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

- New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets

- Towards Sustainability Foundation