Remember from Part 1 of this post that we (I and many great colleagues) are studying what biopesticides can add to effective disease management of cucurbit powdery mildew and white mold. After “what is a biopesticide?” the next most common questions about this project are about the specific biopesticides we’re testing:

- How do they work?

- Can I tank mix them with other pesticides or with fertilizers?

- Do I need to use these products differently than I would use a chemical pesticide?

Today’s post will try to answer those questions.

Modes of action – How do they work?

As you may recall from February’s post, biopesticides work in different ways, and the five biofungicides we’re studying cover the range of these modes of action.

Eats pathogen

The fungus active ingredient of Contans (Paraconiothyrium minitans strain CON/M/91-08; formerly called Coniothyrium minitans) “eats” (parasitizes and degrades) the tough sclerotia of the fungus, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum that causes white mold. Sclerotia survive in the soil from year to year. However, for this strategy to be effective, the fungal spores within Contans have to first make contact with the sclerotia. The time between colonization and degradation of sclerotia is about 90 days.

Makes antimicrobial compounds

The active ingredients in Serifel and Double Nickel are bacteria – same species but different strains. They both produce compounds that are harmful to plant pathogens (antimicrobial). According to the manufacturer, most of the foliar efficacy of Double Nickel is due to the antimicrobial compounds already present in the container. But the manufacturer notes that some of the efficacy also comes from the live bacteria that are responsible for this product’s other modes of action, especially the induction of plant resistance (more on this later). The strain of bacteria in Serifel has been formulated so that it contains only living bacteria (no antimicrobial compounds). The manufacturer’s goal is for the bacteria to produce antimicrobial products unique to the specific environmental conditions after application. Double Nickel and Serifel are examples of different strategies for using antimicrobial-producing bacteria to fight plant diseases. Our goal is to explain how the products work; not tell you which strategy is better.

Excludes pathogen

The bacteria in Double Nickel and Serifel also can protect plants from disease by growing over (colonizing) the plant so that there is no space or nutrients available for pathogens. How important this mode of action is to the efficacy of Double Nickel depends on the setting and time of year (according to the manufacturer). Cucurbit leaves exposed to sun, heat, and dry air are not great places for bacteria to grow, and pathogen exclusion is not likely to be very important in protecting cucurbit leaves from powdery mildew. The antimicrobial MOA is more important here. Apple blossoms being protected from fire blight in the early spring could be a different story. The bacteria in Serifel tolerate a wide range of temperatures in the field, but the manufacturer recommends applying this product with a silicon surfactant to help the bacteria spread across the plant surface better.

Induces plant resistance

Plants have mechanisms to defend themselves. Some pathogens succeed in causing disease when they avoid triggering these defenses, or when they infect the plant before it has a chance to activate these defenses. Some biofungicides work by triggering plants to “turn on” their defense mechanisms. This is called “inducing plant resistance.” It is the sole mode of action of the bacteria in LifeGard, and one of the modes of action for the active ingredients in Double Nickel, Regalia, and Serifel.

Promotes plant growth and/or stress tolerance

The last biofungicide being studied in this trial has a plant extract as an active ingredient, instead of a microorganism. Regalia works by both inducing plant resistance, and also promoting plant growth and stress tolerance. Some of the other products in this trial also share these MOAs. According to the label, some crops treated with Regalia produce more chlorophyll or contain more soluble protein. This final MOA (promotion of plant growth and stress tolerance) is also sometimes shared with “biostimulants”. But remember that “biostimulant” is not currently a term regulated by the EPA. This may be changing in the future, so stay tuned. Biostimulants enhance plant health and quality. They are not registered as pesticides, and must not be applied for the purpose of controlling disease. Make sure you read and follow the label of any product you apply.

Best practices – How do I use them?

We’ll get to some product-specific details in a minute, but first some notes about best uses for all five of these products.

- They need to be used preventatively. For biofungicides to eat pathogens, exclude them from plants, induce plant resistance, or improve plant growth and stress tolerance, they need to beat the pathogen to the plant. It takes time for the plant to fully activate its defenses, even if “flipping the switch” to turn those defenses on happens quickly. The same applies to promoting plant growth and stress tolerance. And if you want the beneficial microorganism to already be growing where the pathogen might land, of course you need to apply the product before the pathogen is present. Microbes that produce antimicrobial compounds also work best if they are applied when disease levels are low.

- Use IPM. These biofungicides (and most, if not all, biofungicides) were designed to be used with other pest management strategies like good cultural practices, host resistance, and other pesticides. For example, they can be included in a conventional spray program to manage pesticide resistance.

- Mix what you need, when you need it. Don’t mix biofungicides and then leave them in the spray tank overnight. Some products may need to be used even more promptly. Check the label.

- Store carefully. Generally, away from direct sunlight and high heat. Follow the storage instructions on the label.

- They have short intervals, but still require PPE. One of the benefits of biofungicides is short pre-harvest intervals (PHIs) and re-entry intervals (REIs). All five of the products we’re studying have a 0 day PHI and a 4 hour REI. But they all still require personal protective equipment (PPE) when handling and applying them. Read and follow those labels!

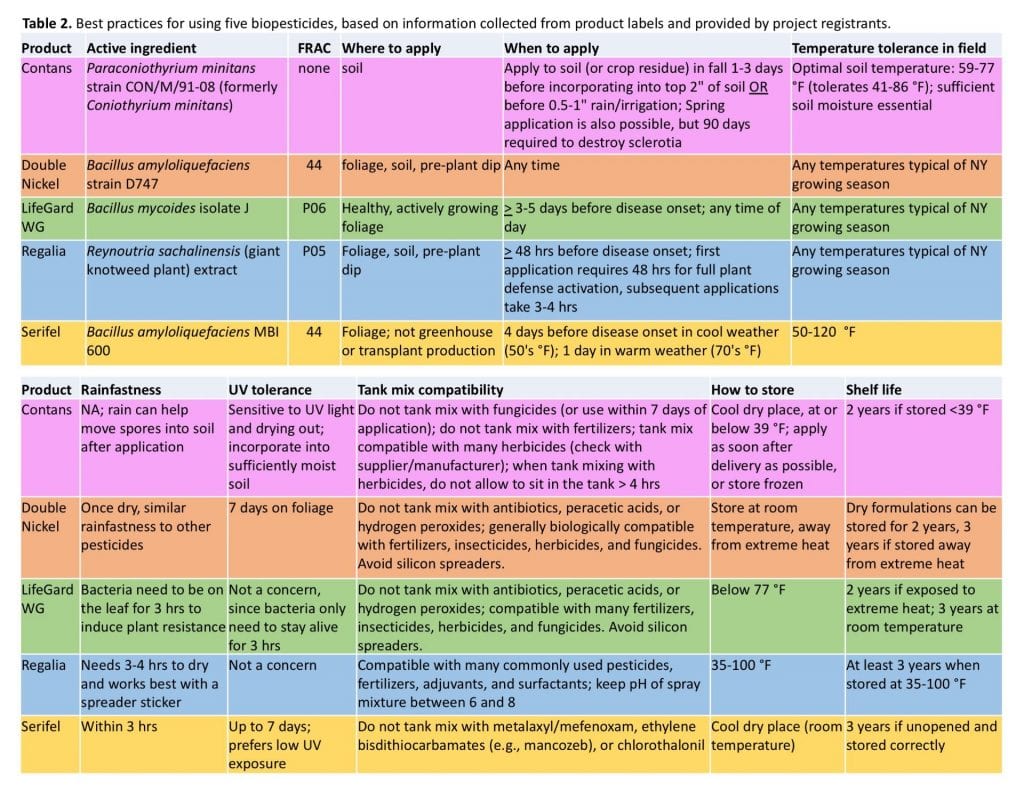

- Tank mixing best practices still apply. The table at the end of this post has details about biological compatibility of these products in tank mixes, as reported by the manufacturers. But just like other pesticides, you need to follow the label instructions for mixing. If you have questions about a specific tank mix partner, confirm compatibility with a company rep. Do a “jar test” if you are mixing two products for the first time and want to know if they are physically compatible.

Biopesticides (especially those that contain living microorganisms) often need to be handled and used differently than chemical pesticides. They may be more sensitive to temperature, moisture, or UV light, which may impact the best time or place to apply them. And of course you don’t want to tank mix a living microorganism with something that will kill the good microbe. (Cleaning your tank well between sprays is always recommended, whether or not you are using a biopesticide.) The following table summarizes details for the five products we’re studying provided by the manufacturers – from product labels, company websites, and conversations with company reps. We have not personally tested this information.

We’ve created handouts that summarize the designs of both the cucurbit powdery mildew and the white mold trials, the modes of action of the five biofungicides we’re testing, and the best practices information presented above.

cucurbit powdery mildew biofungicide trial summary

white mold biofungicide trial summary

Stay tuned for Part 3 of this post – results from our first year of field trials!

This post was written by Amara Dunn (NYS IPM) and Sarah Pethybridge (Plant Pathology & Plant-Microbe Biology, School of Integrative Plant Science, Cornell University). Thank you to the New York Farm Viability Institute for funding.