Flavor Networks: Understanding Food Pairing vs. Food Bridging:

This article from the MIT technology review discusses limitations of the “food pairing” hypothesis and explains “food bridging” as a better way to think about how ingredients are paired together. The food pairing hypothesis proposed that ingredients are combined into cohesive dishes when they share flavor molecules. After researchers analyzed a network of ingredients and their links, it became clear that the food pairing hypothesis could only explain ingredient combinations in North American and Western European dishes. In East Asia, ingredients that didn’t share flavor molecules were combined.

At first, the East Asian situation seemed puzzling—why would two ingredients that didn’t share flavor molecules go together? But examining the broader network of ingredients and flavors revealed that, when two ingredients did not share flavor molecules, they were combined in a dish along with a third ingredient that shared flavor molecules with both of the other two. This phenomenon was termed “food bridging.”

The shift from wide acceptance of the food pairing hypothesis to that of food bridging can reveal the ways in which networks and their properties help us understand phenomena in the world.

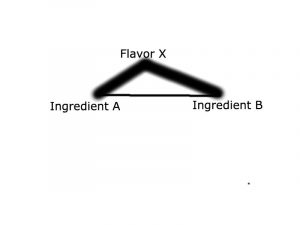

The figure below demonstrates how food pairing can be understood as simple manifestations of triadic closure.

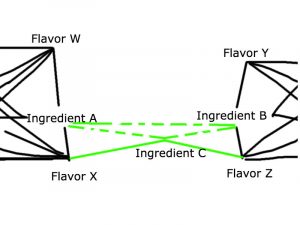

As the above figure shows, Ingredient A has flavor X and Ingredient B has flavor X, so, as the theory of triadic closure would predict, Ingredient A goes with Ingredient B. The picture becomes more complex when we begin to discuss food bridging. If A and B have no flavors in common, it would seem that they should not go together. However, looking at flavors in the same way we looked at people in lecture, there are so many, that all it takes is one local bridge in order to connect one component to another. Food bridging can be thought of as introducing the ingredient that connects one flavor component to another.

Before the introduction of Ingredient C, Ingredients A and B would not be combined because they are in separate components. Ingredient C, however, has Flavor X and Flavor Y. Ingredient C’s connection to Flavors X and Y leaves two open triangles: CZB and CXA. According to triadic closure, Ingredient C should link to A and B in order to resolve the tension (Flavor X is in A and C, so A goes with C; Flavor Z is in C and B, so C goes with B; C goes with A and C goes with B, so A goes with B).

Food scientists have discovered the universal principle behind successful recipes. (2017, April 20). Retrieved September 18, 2017, from https://www.technologyreview.com/s/604207/flavor-networks-reveal-universal-principle-behind-successful-recipes/