The Tragedy of the Commons and Project Ocean Shield

We’ve mentioned the applications of Networks, graph theory, and game theory to the field of international relations in the context of officially positive or officially negative relationships; we can also use the study of game theory to understand the challenges nation states face in the process of international cooperation. With issues such as climate change or international security, solutions such as globally reduced carbon emissions or peacekeeping cooperations seem mutually beneficial, but suffer a critical issue. Climate change and international security are challenging for international organizations because, among other reasons, they deal with the provision of public goods. A public good is any commodity, physical or otherwise, that is non-rival – my partaking in the good does not limit your share of the good – and non-excludable – the good is available to everyone. For example, clean air and safe seas are international public goods, because we all share the same air and seas, and we don’t necessarily have to contribute to the cleanliness of the air or the safety of the seas. This is the source of the problem. Let’s use the example of clean air and make up a simplified game.

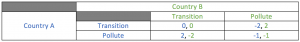

Say there are two countries living on a planet, sharing the same atmosphere. They each have successful industrial sectors, but the increase in manufacturing has lead to unhealthy levels of pollution. As a result, the two countries have agreed to transition their industries to green technology. For simplicity’s sake, we also assume that these countries are of equal population and suffer an equal amount as a result of the pollution. The players in this game are the two countries, and the strategies for both countries are either to make the proposed transition to green technology or to continue polluting the atmosphere. The payoffs are more complicated. Let’s assume that the two factors affecting the countries’ payoffs are the state of the environment and the cost of industry. Let’s say that transitioning to green technology reduces a country’s payoff by 5, but improves the state of the environment, so everyone gets 3 added to their payoff; let’s also say that if neither country transitions, the poor state of the environment will give both countries a payoff of -1. The table looks like this:

These payoffs don’t necessarily reflect real values of development, climate change, industry, etc. but they illustrate a point. The dominant strategy for both players is to continue polluting, because if either country were to transition, the other country’s best response would still be to pollute, which leaves the first country worse off than if they were both polluting. The countries cannot commit to cooperation because of their self interests. This is the exact same problem we see in the Prisoners’ Dilemma. In both games, the players fail to cooperate on a socially optimal pair of strategies because they have no way to commit to a technically irrational choice (choosing the socially optimal over self interest). You can see easily how this dilemma could be applied to hundreds of countries, each with a vested interest in the state of the environment – their incentive isn’t to contribute, but rather to “free ride” off of the countries who do contribute. If every country does better by not contributing than contributing, nobody is going to contribute, even if it means a much worse world for everybody. This is one example of an obstacle to cooperation called The Tragedy of the Commons. These problems are often called “Collective Action Problems”.

In reality, there are situations with similar issues but different payoffs that can overcome this obstacle. One such situation is the provision of public goods by a hegemon, a single actor who dominates their field and who is significantly larger or more powerful than the other players. The United States is often considered a hegemon of trade in certain areas, as we will soon find out. One solution to the previous problem arises when one giant player, the hegemon, uses a public good far more than the other actors, and thus has an incentive to provide it by himself. The hegemon needs to use the public good to an extent such that even if the hegemon provides the good by himself, he still does better than if he didn’t provide the good. Taking the previous example, if one of the countries was several times larger than the other country, and thus had more land and population to take care of, it would make sense for them to transition (given the same payoffs as above) because they stand to gain a lot from the change. Another example is the international cooperation Operation Ocean Shield, which protects the seas from pirates surrounding the horn of Africa. Safe seas are a public good – anyone can use these seas, even if they didn’t pay for Operation Ocean Shield – which would normally make such an operation difficult. However, the United States performs a disproportionate amount of the trade in that area, and thus still has something to gain from the protection of the seas, even if they have to pay for it. The American payoff is positive. This is reflected in the deployed vessels: the United States provides far more ships than any other country to the Operation. The hegemonic provision of public goods is one solution to The Tragedy of the Commons: it is not the only one, and there are obvious drawbacks to the presence of a hegemon, but it is interesting to see real-life solutions to one of the oldest and most popular game theory dilemmas.

Sources: