As we start August in New York, I hope that your gardens and fields are full of abundant blooms, vegetables, fruits, or all of the above. They may also be humming, buzzing, or making other noises as a result of resident insects. If you find an unfamiliar insect, you might be wondering: Is it a friend or a foe? Here are some friendly insects – natural enemies of pests – you might encounter.

Lady beetles

Adult lady beetles are some of the most easily recognized natural enemies. For example, most would know that this sevenspotted lady beetle is a friend. But lady beetles come in many different stripes – err – spots. Here’s another lady beetle that might not be as familiar, but is an equally good predator.

Immature lady beetles look very different from adults. But the larvae are voracious predators, and leaving the pupae undisturbed means you’ll soon have more adult lady beetles around. In addition to aphids, lady beetles will eat whiteflies, thrips, mites, and eggs of other insects.

If you’d like to identify the lady beetle species you’re finding in your garden, check out these resources from The Lost Ladybug Project.

Lacewings

Similarly, while you may be more familiar with the adult lacewings (which can be green, as well as brown), in some lacewing species it’s only the larvae with their formidable jaws that are munching on pests (generally the same ones that lady beetles eat). Adult lacewings will eat pollen and nectar (and some species also eat other insects).

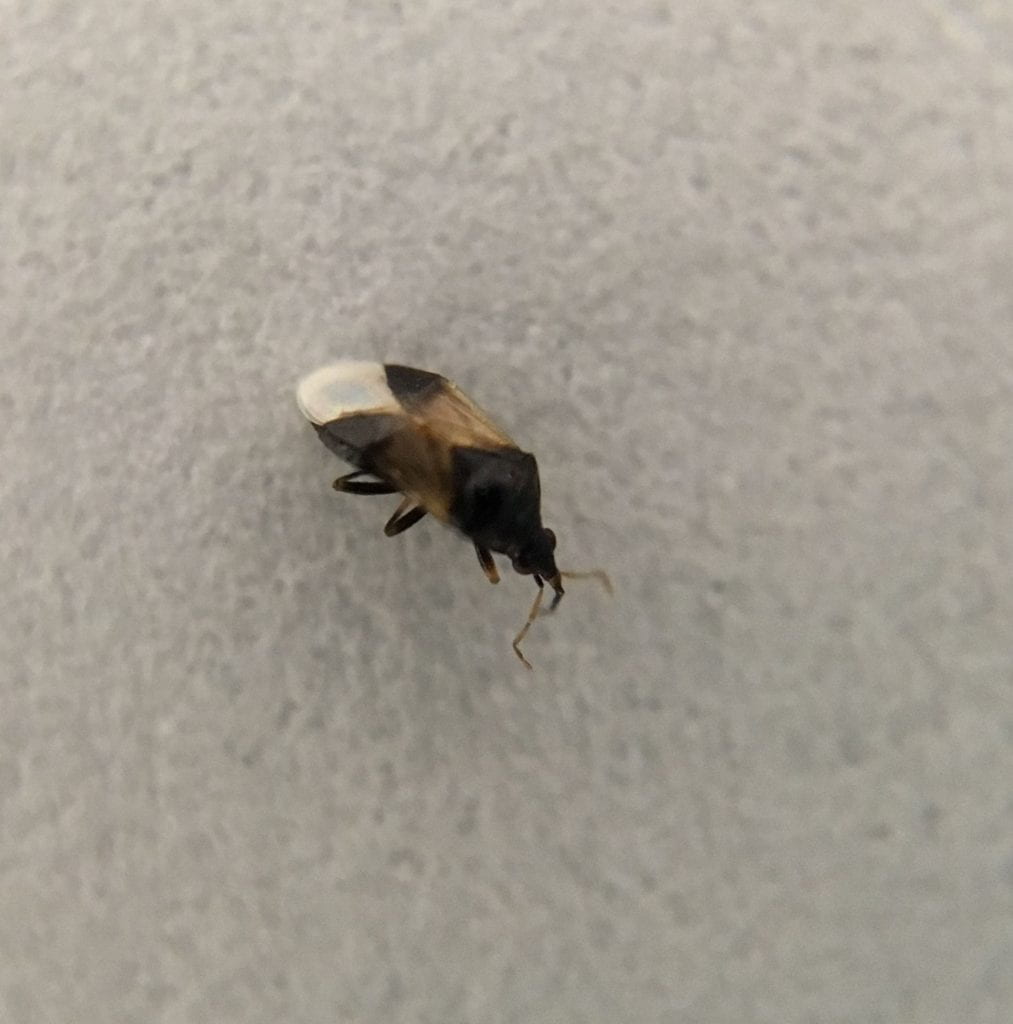

Minute pirate bugs

This friendly bug (and it is a true bug!) can be hard to spot because it’s so tiny; truly minute. If you get a chance to look at this (< ¼”) insect with a hand lens, you’ll notice a white diamond shape towards its rear, with a black diamond shape behind its head. At least that’s what the adults look like. Here’s one searching for thrips on a sign at a corn maze. The immature (or nymph) minute pirate bugs are orange and look not much like the adults. In keeping with their size, minute pirate bugs eat small pests like aphids, mites, thrips, and insect eggs. They also eat pollen and nectar, which is probably why I often bring a few inside with me when I cut flowers from my garden. Those same mouthparts that are great at eating pests can also give you a small (but startling) pinch. But it doesn’t hurt much, and if you leave them undisturbed, both you and the pirate bugs will be happier.

Hover flies

Sometimes hover flies (also called syrphid flies) are incorrectly called sweat bees. Sweat bees are true bees. While many hover flies are black and yellow striped, and some look quite a lot like bees, they are flies. True to their name, hover flies are often spotted hovering around flowers. Here are two tips for distinguishing hover flies from bees:

- Hover flies have big eyes that take up most of their head; bee eyes are usually smaller and oval-shaped

- Hover flies have only two wings; bees have four

Immature (larval) hover flies are the ones that are eating pests on your plants. They look like small worms, and may come in slightly different sizes or shapes. But they love to eat aphids, whiteflies, and scales.

(Predatory) stink bugs

None of us are happy to find stink bugs (usually brown marmorated stink bugs, to be specific) invading our homes, but there are many more stink bug species, and some of them are excellent predators. I know, the one above happens to be eating a monarch caterpillar, but they will eat pest caterpillars and other insects, too. The advantage of generalist predators is that they will eat all kinds of pests. The disadvantage is that they may also eat some insects that aren’t pests. This is just part of a balanced ecosystem in your garden or field.

It can be difficult to distinguish a predatory stink bug from a pest stink bug, without looking closely at its proboscis (straw-like mouthparts used for sucking either plant or bug juices), but Virginia Cooperative Extension has a nice field guide available here, which can help. Or you could spend some time observing the stink bug to see if it’s eating a plant or another insect.

Spiders

Spiders (examples on the left and middle in the above picture) and harvestmen (example on the right) may make some people feel uncomfortable, but both are generalist predators, and therefore good to have around. The spiders you are likely to find in New York are nearly all non-venomous, so welcome them without fear. More info about common spiders of NY can be found here.

Wasps

If you are growing a diversity of flowers that produce lots of pollen and nectar, you may also see a diversity of wasp visitors. Most are unlikely to sting you, and even wasps like yellow jackets or hornets that may sting you are likely also looking for caterpillars and other insects to eat. Many wasps (including tiny ones you won’t notice and larger ones that you will) can also kill pests by laying their eggs in or on them. These are called parasitoid wasps. So if wasps aren’t hurting anyone, leave them alone. Of course, if stinging wasps are building a nest on or near a structure where they are likely to be disturbed by people, action may be required. Learn how to use IPM for stinging wasps here.

Other flies

Besides hover flies, there are a whole lot more flies visiting gardens and fields, and many will either eat or parasitize pests. The robber fly pictured above is especially large and is a great predator. Of course, there are plenty of flies you don’t want around. For more info on IPM for flies around your home, you can look here. You can find resources for managing livestock flies here.

And there’s more!

This is by no means an exhaustive list of insect natural enemies. For example, there are a variety of other true bugs, including big-eyed bugs, damsel bugs, assassin bugs, and ambush bugs that will eat pests in your garden or field. The ambush bugs are the easiest to recognize.

And, this list doesn’t touch on most of the ground-dwelling natural enemies (although some spiders are predominantly found on the ground. I’ll cover those in another post.

This post was written by Amara Dunn, Biocontrol Specialist with the NYSIPM program. All images are hers, unless otherwise noted.

This work is supported by:

- New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets

- New York State Department of Environmental Conservation

- The Towards Sustainability Foundation