And How…

January 18th, 2019

In the middle of frigid January, I would say I am coming around to this idea of working inside at the desk and not out in the barn or the field! This week I have been learning and doing more cleaning of yield data.

Using a USB drive, the data can be taken straight from the combine or chopper cab monitor and read into the SMS Software. On SMS the yield data is sorted using geospatial data from GPS locating into the farmer’s set field boundaries, also made using GPS systems. Information about the crop, growers, fertilizers, field history, and almost any other field attributes can be added too. Once the data is in manageable field-sized packages from fiddling around with it on SMS, the data can be sent into Yield Editor to be ‘cleaned’. Yield Editor is where, by tinkering with and adjusting the settings of the machinery sensors, you can manually compensate for the error variables I mentioned last week (variable speeds, stops, wet/dry, flow delay, operators who get funky with it, etc.).

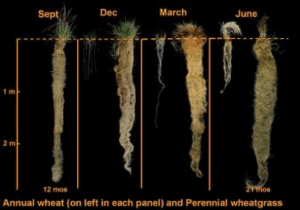

On Yield Editor, data fed in from SMS are laid out chromatically and sometimes vaguely discernible patterns of high vs. low values show up within the rainbows of color. Then, constants for the variables can be set so the patterns line up into more easily distinguishable features that can actually be attributed to something such as slope of the field, a wet/dry spot, a tile line, a common traffic path, etc.. The picture to the left shows some of the variables for which constants and limits can be added to manipulate the data. Below, an example from the NMSP Protocol “Processing/Cleaning Corn Silage and Grain Yield Monitor Data for Standardized Yield Maps across Farms, Fields, and Years”* shows the change in the data points when a flow delay is accounted for. A pattern of a low yielding zone becomes more linear, and perhaps lines up with a wet spot, different soil type, or tile line on the field.

This cleaned data from Yield Editor can then be read back into SMS, which can be used as an extremely beneficial tool for crop planning and management by the farmer. With cleaned data to work with, management practices can be even more targeted and precise.

This type of diagnostic can prove useful to a farm. If a low yielding zone, upon further investigation, is found to have a drainage or erosion issue, measures can be taken to fix the problem. Furthermore, if there is an issue like a soil type that perhaps needs to be fertilized/treated differently, it is easier for the farmer to make zone prescribed planting or fertilizer prescriptions to optimize production in each zone. Along the same lines, if the farmer sees that sections of his field year after year are extremely high yielding, they may change their population density to better utilize the area or reduce their fertilizer expenditure on that zone save money and be economical. By cleaning the data, it allows for accurate measurements and clearer boundaries that can lead to clearer management zones for the farmers to work with. I hope to explore this kind of management on the farm at Osterhoudt Farms this summer. The NMSP Lab has given me so much information to work with and explore on the farm!

*Official Reference:

Kharel, T., S.N. Swink, C. Youngerman, A. Maresma, K.J. Czymmek, Q.M. Ketterings, P. Kyveryga, J. Lory, T.A. Musket, and V. Hubbard (2018). Processing/Cleaning Corn Silage and Grain Yield Monitor Data for Standardized Yield Maps across Farms, Fields, and Years. Cornell University, Nutrient Management Spear Program, Department of Animal Science, Ithaca NY.