Hey everybody,

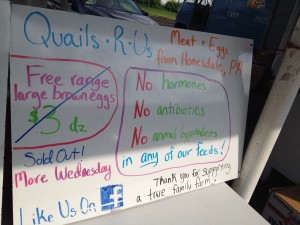

As my days here at Quails-R-Us whiz by, I’m startled to realize that I have very little time left here on the farm. After months of working so closely with the owners, living with them, taking meals with them, hearing firsthand their struggles and future plans, I’ve found that somewhere along the line I stopped thinking of this summer as a temporary arrangement and more as the beginning of a long-term partnership. During this summer I have been treated as a partner in the business, a position I’m honored to have held. Often I was asked my opinion on some managerial decision that would impact the farm well after I was gone, and I always gave my answer as if this really were my farm. Without realizing it, I started considering the success of this farm as integral to my future as it is to that of the owners. The farm’s struggles became my struggles, and I devoted as much time and effort to fixing them as I would any hardship in my own life. Any victory the farm had – getting into a new market, having a favorable article written about us in the local newspaper, securing a new CSA member – had me as delighted as if I would be benefiting from that victory myself.

Every minute I spent working alongside the owners was less for me and my education and more for the continued success of the farm. Somewhere between my arrival on the farm and now, I became invested, and the continued improvement of the economic and environmental sustainability of the business became my sole goal. I’ve been giving 110% every day to make sure this farm survives. Now I find it difficult to remind myself that this is just a temporary job, and in just a few short weeks I’ll be far away from the beautiful sunlit meadows I’ve come to love. I’ve had an absolutely wonderful summer, filled with hard work and many memories, and I’m still a bit confused as to where all my time went. It’s a bit of a shock to remember that no, I won’t be here in November to make sure all the customers ordering their Thanksgiving turkeys are satisfied. And no, I won’t be here next lambing season to help birth and eartag new additions to the flock. It’s so strange, after weeks of thinking of this farm as my farm, as my future, and doing so much for its long term success, that I’ll be leaving it behind to continue my life. Maybe I’ll return someday to continue to help manage it, and maybe not. The thought makes me a little melancholy.

I hardly feel that all my hard work is for nothing, though. I’ve learned so much from this experience, lessons you could never get from a textbook or a lecture. While I hardly romanticized farming before this job, I definitely was not fully aware of how much it takes out of you. I regularly have been working seventy hours a week, falling into bed exhausted at the end of the day, with barely the energy left to eat, much less do all the hiking and adventuring I thought I was going to do this summer. And still I have had more downtime than my bosses, who regularly wake up at 4am to start the day’s chores while I’m still snoozing, and who work longer into the night every night on paperwork and number-crunching. I knew before that a farmer wears many hats: soil scientist, veterinarian, carpenter, marketing specialist, mechanic. Now I know that farmers often also must know the less hands-on fields: web design, the ins and outs of workers comp, how to navigate market politics, and a lot about licensing, permits, and taxes. Many of the farmers I developed friendships with this summer cited a love of the land and of nature as the reason they kept with farming, despite all its hardships. And yet often we all are so busy farming, rushing from one chore to the next, that taking the time to consider and appreciate the natural landscape we work in gets put on the back burner. All farmers, it seems, are on the brink of survival. You’ll never get rich in farming. There always will be another crisis to attend to – an outbreak of footrot, a broken tractor, a very vocal unsatisfied customer, a bill that’s overdue to be paid. But, if you do it right, you will have a good sense of satisfaction with your life. You’ll be working hard to put food on the tables of your customers. You’ll have rewarding relationships with your community, fellow farmers and consumers alike. You’ll spend time with animals, spend time with growing things, spend time in nature every day. You’ll go to bed knowing you made a difference. And, to me, that will be what makes it worth it.

More soon.

Lauren

behind the scenes. I suppose like any group, the vendors of a market have disputes and tensions. Some are resolved cordially, usually through a market manager or a vote, some not so cordially, and some are never resolved, but just simmer just under the surface, making enjoying the market a very difficult prospect. All vendors are there for the same reason: to make money while helping the consumer eat fresh, local, and sustainable food. It’s a shame that such petty disagreements can destroy the sense of community in a market so easily.

behind the scenes. I suppose like any group, the vendors of a market have disputes and tensions. Some are resolved cordially, usually through a market manager or a vote, some not so cordially, and some are never resolved, but just simmer just under the surface, making enjoying the market a very difficult prospect. All vendors are there for the same reason: to make money while helping the consumer eat fresh, local, and sustainable food. It’s a shame that such petty disagreements can destroy the sense of community in a market so easily.