Our introductory lab meeting was the first time I had heard about Kernza. It was spoken of with such enthusiasm and excitement; however, I didn’t fully understand why. After working on our Kernza experiment and doing some research, I now emulate that same enthusiasm.

Kernza is a perennial grain that was developed by the land institute in Kansas. Like I’ve mentioned there has been tremendous excitement about the idea of a perennial grain. Since the grain is perennial, it can grow throughout the year with roots that can survive the winter. Other grains, for example, corn and wheat (annual crops), have to be planted each year. This is important because crops that are replanted each year often require more fertilizer and pesticide application. Also, in order for annual crops to be planted, the ground must be tilled. As I discussed in my last post, tillage is a damaging practice to soil health. Kernza does not require tillage because it doesn’t need to be replanted each year, therefore improving soil health. What is also unique about Kernza is the large root system it possesses. This allows kernza to better acclimate to changes in the environment. The larger root system also helps avert soil erosion which has become a huge issue in agriculture. Soil erosion also leads to the runoff of nitrogen into waterways which have caused events like the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico. Scientist that developed Kernza also believe it can sequester carbon. I find this aspect to be very exciting because not only will Kernza be improving soil health, but it could also potentially help against global climate change.

Graphic comparing the root depths of Kernza and Wheat. Kernza is on the right and Wheat is on the left.

While this crop is very exciting there are still some kinks to work out. First, The grain produces a smaller yield than other grains which has some doubting its economic viability. Second, domesticated grains such as wheat have been bred to be shatterproof, meaning the seeds stay on the stem of the plant. As of now, Kernza still shatters leading to a potential decrease in yield. Lastly, the use of the grain is still being fine tuned.

Our lab is one of a few labs in the nation researching methods of Kernza management which makes this experiment extra exciting! There are two Kernza experiments currently taking place. The first experiment is analyzing amounts of fertilizer input, primarily nitrogen, to see how much fertilizer optimizes yield. On top of that, the Kernza will be harvested at different times during the season to see what times of harvest optimize yield. This type of experiment shows how Kernza really is in the early stages of development and implementation.

The other experiment investigating the potential benefits of Kernza in a polyculture with legumes such as clover. Since Kernza requires nitrogen inputs, this experiment aims to limit fertilizer inputs by planting legumes which fix nitrogen into the soil.

My role in the Kernza experiment has been cleaning up the field, more specifically deheading wheat that had reseeded in the field. The field that we are using for the Kernza was previously a wheat field. Some of the wheat wasn’t taken up by the harvester and reseeded. As a result, there is wheat throughout the kernza field. There was a good six days I and other members of the lab spent in the Kernza field cutting and removing wheat heads in hopes it won’t be able to reseed and not come back next year. This is somewhat of a “buzzkill” for such an amazing project and even though we’ve worked six days we still have half of the field to do.

A picture of the Kernza plot. Kernza is the bluish, slimmer, and taller stemmed plant. The wheat is the greener, thicker, and shorter stemmed plant.

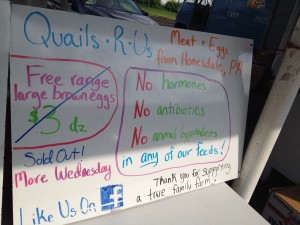

behind the scenes. I suppose like any group, the vendors of a market have disputes and tensions. Some are resolved cordially, usually through a market manager or a vote, some not so cordially, and some are never resolved, but just simmer just under the surface, making enjoying the market a very difficult prospect. All vendors are there for the same reason: to make money while helping the consumer eat fresh, local, and sustainable food. It’s a shame that such petty disagreements can destroy the sense of community in a market so easily.

behind the scenes. I suppose like any group, the vendors of a market have disputes and tensions. Some are resolved cordially, usually through a market manager or a vote, some not so cordially, and some are never resolved, but just simmer just under the surface, making enjoying the market a very difficult prospect. All vendors are there for the same reason: to make money while helping the consumer eat fresh, local, and sustainable food. It’s a shame that such petty disagreements can destroy the sense of community in a market so easily.