Balancing Networks to Explain Antitrust

In 1998, the FTC ruled that Toys ‘R’ Us had ruled that Toys ‘R’ Us violated U.S. antitrust law (i.e., The Sherman Act) when it orchestrated what the Court considered to be a horizontal boycott of warehouse clubs (e.g. Costco, BJ’s, etc.) that were able to offer lower prices than Toys ‘R’ Us. Toys ‘R’ Us had crafted an agreement with major toy manufacturers that heavily restricted how manufacturers could do business with warehouse clubs, and as a result, Toys ‘R’ Us would maintain its large share of the toy distribution market. In 2000, the US Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit affirmed the FTC decision, and in 2011 Toys ‘R’ Us had to pay $1.3 million in pesky FTC fines for not complying with the FTC order.

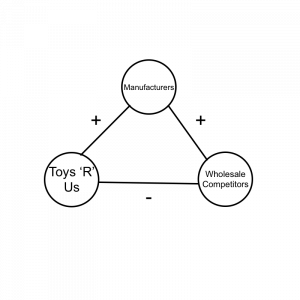

When we briefly discussed balance theory and markets in class, the quintessential example was between competitors: If there is a rivalry between Apple/Samsung and Apple/Google, Samsung and Google have an incentive to collaborate and thus balance the triad. This balancing act becomes a bit more complicated when we look at different levels of markets. When we consider Toys ‘R’ Us, we are considering the relationship between two distribution competitors and a manufacturing competitor, like so:

This unbalanced configuration is the very basic model under which a perfectly competitive market is expected to function: Horizontal competition on the distribution level, but vertical (legal) collusion between the distributor and manufacturer. In the following example, there are two important ways Toys ‘R’ Us could act to create a balanced triad:

- Collude with warehouses: That is, Toys ‘R’ Us could create a cartel with the warehouse companies, thus changing the charge of their relationship from negative to positive. This type of naked horizontal price-fixing agreement is per se unlawful and Toys ‘R’ Us likely wouldn’t stand a chance in court.

- Collude with manufacturers: This is what Toys ‘R’ Us actually did. By colluding with the manufacturers, Toys ‘R’ Us was able to change the charge of the manufacturer/warehouse relationship from positive to negative. This agreement is less nakedly a violation of antitrust law (though still pretty anti-competitive).

Balancing this triad could explain why firms tend to collude. In other words, manufacturer/distributor market models may inherently incentivize anti-competitive behavior. Because this market configuration is unbalanced, antitrust laws likely serve to somewhat inorganically maintain this imbalance in order to promote competition.