Just in time for Alfalfa Cutting

June 12th

Hi everyone! I have joined the Osterhoudt team just in time for their second cutting of Alfalfa hay. Alfalfa is very rich and nutritious and high in protein which makes it an important feed for dairy cows, especially the ones actively producing milk.

Here’s a run-down of an alfalfa hay silage harvest: the standing hay is mowed and left to dry-down to an acceptable percentage moisture. A measure of around 40-45% dry matter (or 55-60% moisture) is reached, then the hay is merged, or raked, into windrows to be fed through the chopper.

(Because Osterhoudt Farms is a Custom Harvesting operation, they harvest fields all over the county. Above is a picture I took of the mergers raking on a beautiful hillside field with a view of Cayuga Lake.)

The chopper uses a giant fan to blow the finely cut hay up the chute and into the trucks. I rode with Walt, the chopper operator, and he even let me try my hand at it!

The trucks haul the haylage to the dairy farm bunk, where it is mounded and packed. The pack is important firstly to keep the product contained, and secondly to compress the hay together to rid the bunk of excess oxygen so it can ferment properly. For silage to ferment without producing a rancid or noxious acid, the microorganisms that perform the fermentation process require an anaerobic environment.

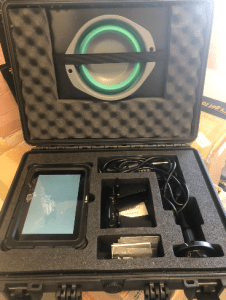

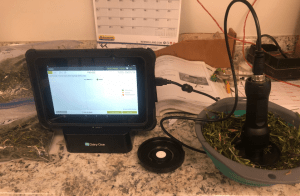

Before sending the choppers out, determining if the hay was at the appropriate moisture content was critical. Because silage is meant to be fermented, a much higher moisture content is acceptable than would be in bales of dry hay. This is an advantage for some farmers because the haylage process allows more days of possible harvest as many consecutive sunny days aren’t needed to dry out the hay. However, it is still important that even in haylage the moisture content is around or just below 60%, so the hay is sampled and tested before harvesting. The farm still checks the moisture through the old tried and true “cooking” method: drying a sample in the oven and measuring water component by difference in weight, but we also had a new moisture sensor that is being tested for use in New York by the Dairy One research lab. Dairy One loaned one of their portable devices to gauge its accuracy and gain information for their database.

And we will get to repeat this whole process a few more times this year! Alfalfa is cut 3 or 4 times per season depending on the weather. ‘Till next time!