Juan Carlos Ramos Tanchez1, Kirsten Workman1,2, Allen Wilder3, Janice Degni4, Paul Cerosaletti4, Dale Dewing4, and Quirine M. Ketterings1

Cornell University Nutrient Management Spear Program1, PRO-DAIRY2, Miner Agricultural Research Institute3, and Cornell Cooperative Extension4

Introduction

Manure contains all seventeen nutrients a plant needs, making it a tremendously valuable nutrient source for crop production. Applying manure to fields can also build soil organic matter, enhance nutrient cycling, reduce reliance on commercial fertilizer, and improve overall soil health and climate resilience. The Value of Manure Project of the New York On-Farm Research Partnership is funded by the New York Farm Viability Institute (NYFVI) and the Northern New York Agricultural Development Program (NNYADP). This statewide project evaluates nitrogen (N) and yield benefits of various manure sources and application methods to corn silage and corn grain crops. Eight trials were conducted in 2023, adding to three trials established in 2022. Here we summarize the findings of the trials conducted in 2023.

What we did in 2023

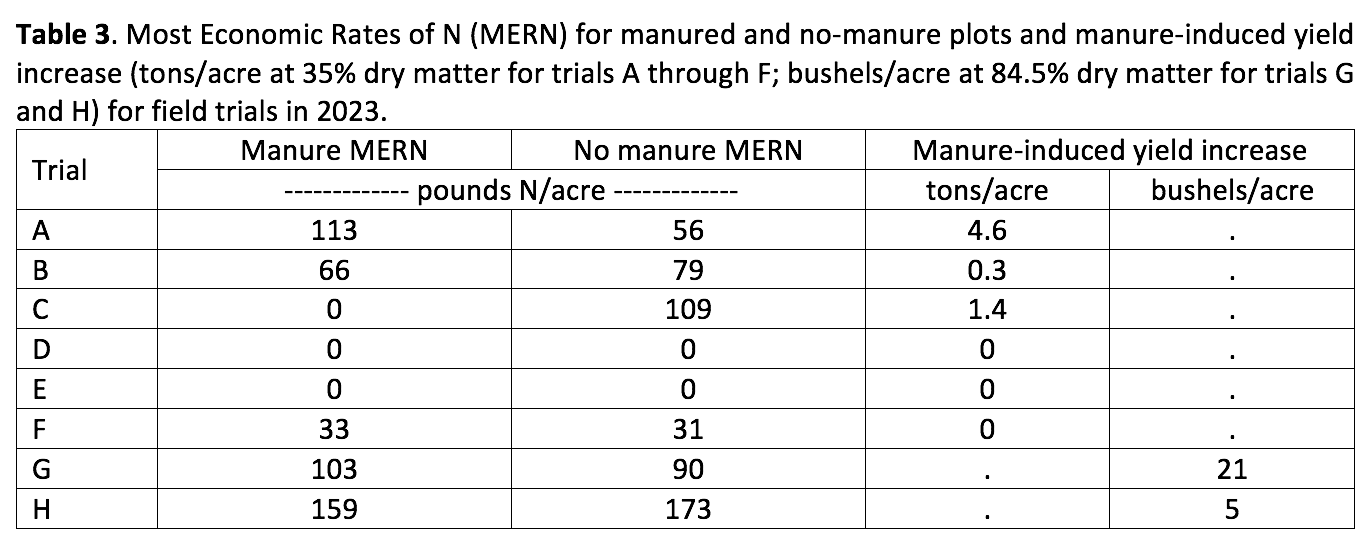

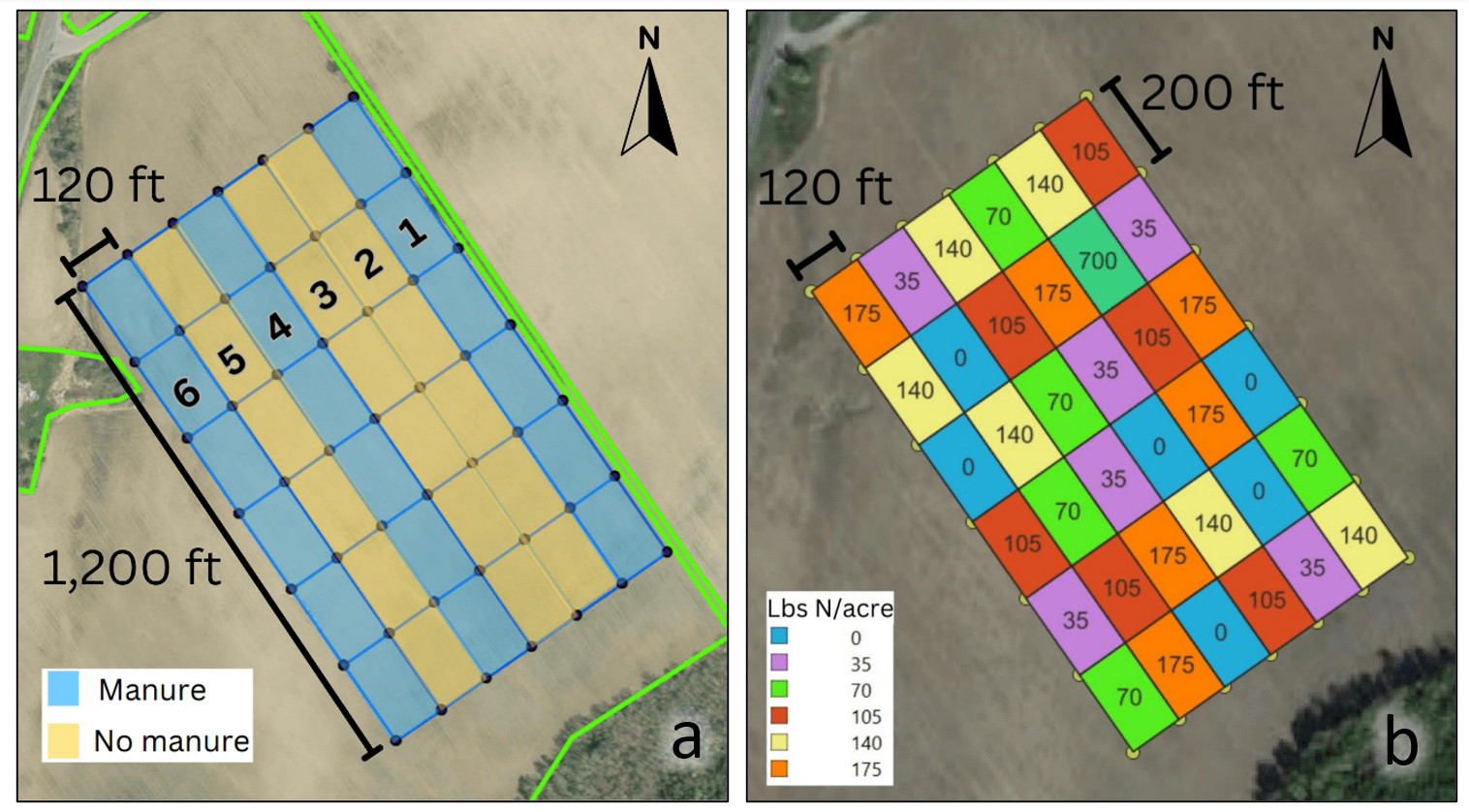

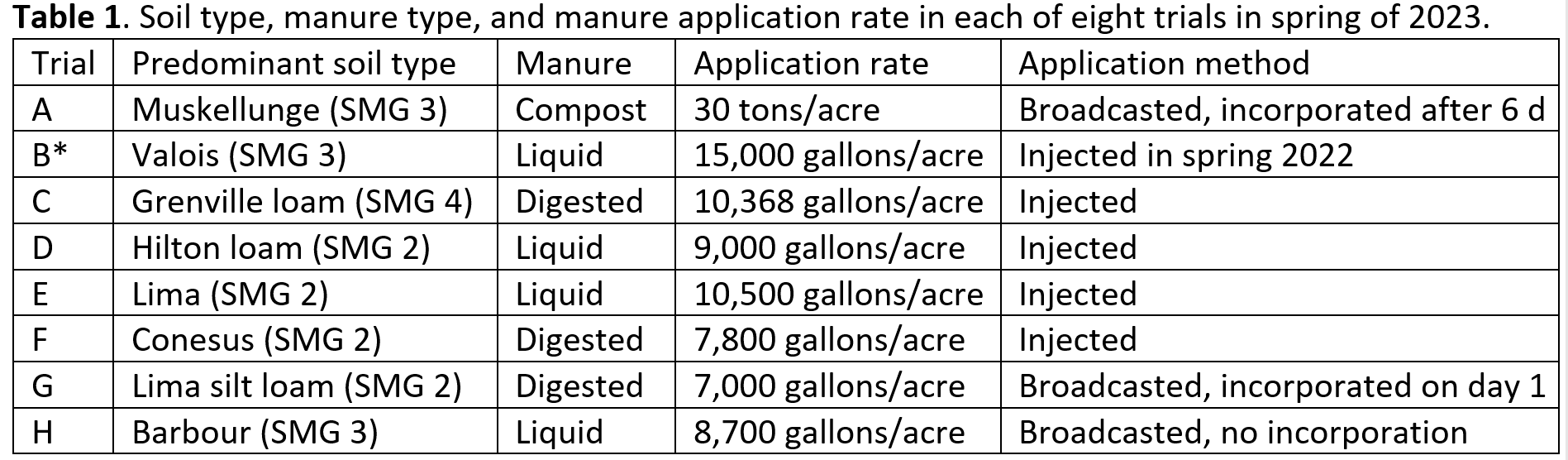

Trials were implemented within commercially farmed corn fields in western (2 trials), northern (2 trials), central (3 trials), and southeastern (1 trial) New York. Each trial had three strips that received manure and three that did not, for a total of six strips per trial (Figure 1a). One trial (Trial B) received manure in spring of 2022. For this trial we tested carryover benefits into the 2nd year (2023). For all other trials, manure was applied in spring 2023 before planting corn. Manure source and application method varied across sites (Table 1).

Strips were 1200-1800 ft long and 35-120 ft wide for all but one site, where strips were 300 ft long 35 ft wide. When corn was at the V4-V6 stage, each strip was divided into six sub-strips (Figure 1b) and subplots were sidedressed at a rate ranging from 0 up to 300 pounds N/acre. Sidedress rates were trial-specific, based on the expected N requirement of each field. For each trial, we measured manure nutrient composition, general soil fertility, Pre-Sidedress Nitrate Test (PSNT), Corn Stalk Nitrate Test (CSNT), yield, and forage quality.

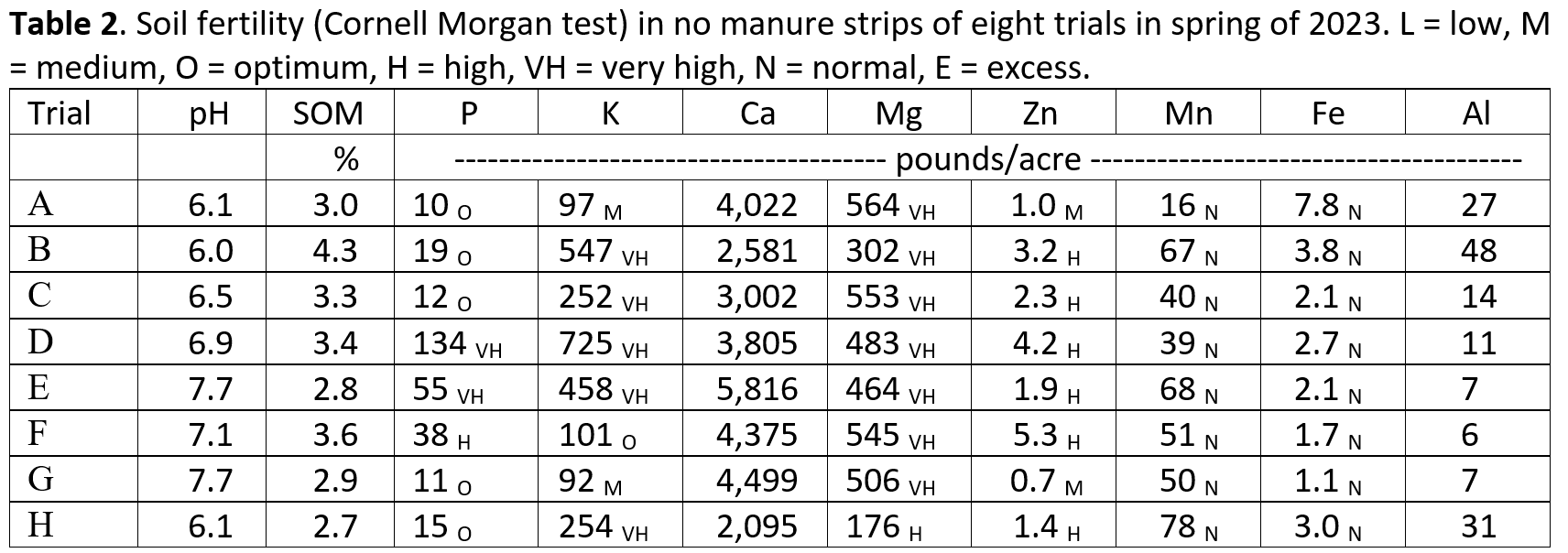

Soil test phosphorus (P) of the trials was classified as optimum (between 9 and 19 pounds P/acre), high, or very high (Table 2). Soil potassium (K) was optimum or very high for six of the trials while trials A and G tested medium in K. Magnesium soil test values were high (> 101 pounds Mg/acre) or very high. Soil test zinc (Zn) was medium for trials A and G (between 0.5 and 1.0 pounds Zn/acre) and high for all other trials. Manganese and iron were in the normal category (< 49 pounds Fe/acre, < 99 pounds Mn/acre).

What we have found so far

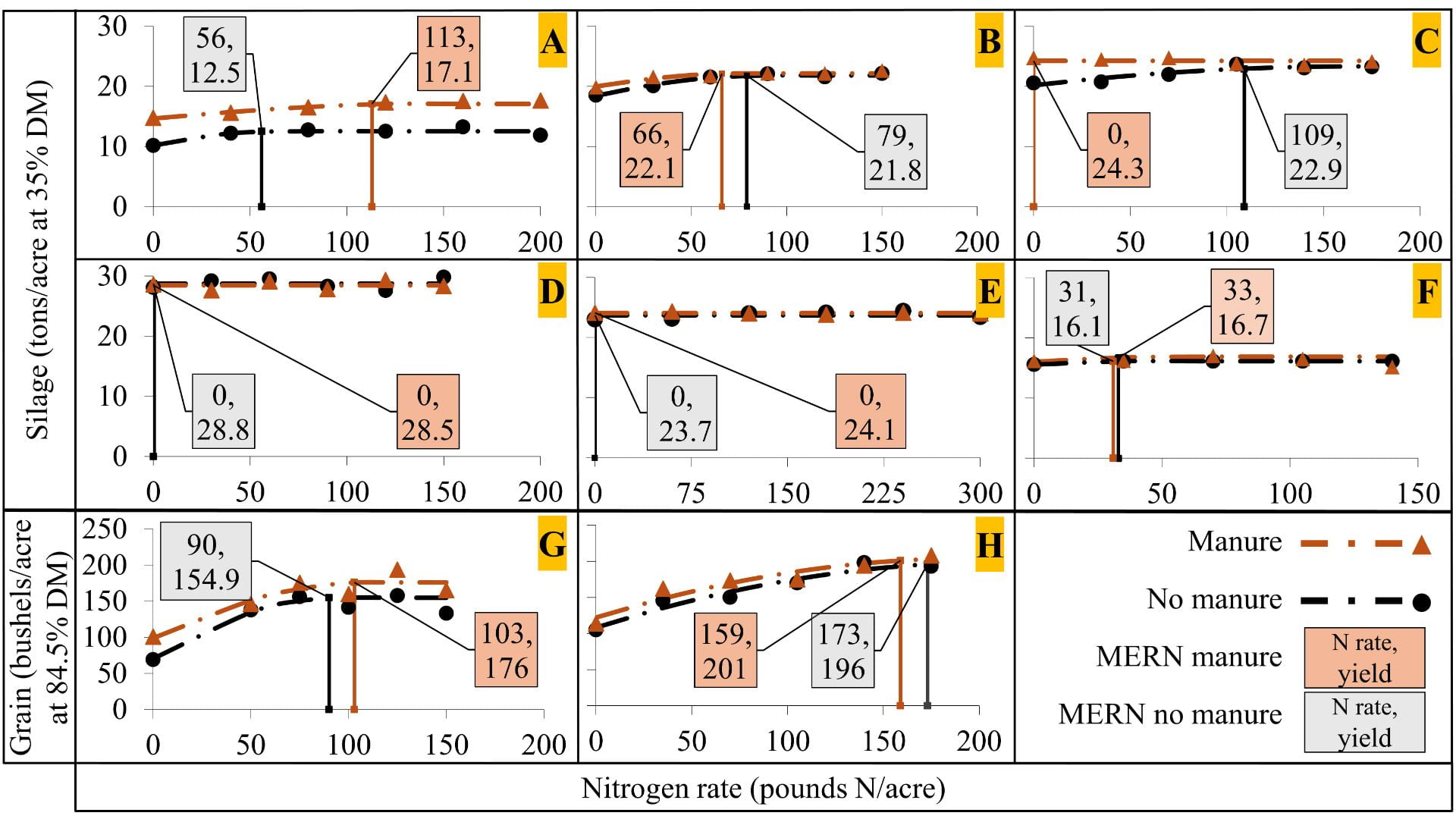

Similar to what we found in 2022, trials differed in their responses to manure and inorganic N (Figure 2). Trials D and E did not respond to manure or N sidedress application likely due to past N credits providing enough N to the crop. In trials A, B, C, G, and H, yield increased due to both manure and sidedress N application. Yields increased in manured plots beyond what could be obtained with fertilizer N by 0.3 to 4.6 tons/acre, and 5 to 21 bushels/acre (Table 3). In trials A and G, the ones with medium K and Zn classification, manure applications increased yield to such elevated levels (4.6 tons/acre for trial A and 21 bushels/acre for trial G), that it also increased the crop’s need for fertilizer N (in other words, the required sidedress N rate also increased). In both trials, manure application shifted soil K levels from medium to optimum and increased K content in silage, suggesting K was yield limiting at these locations.

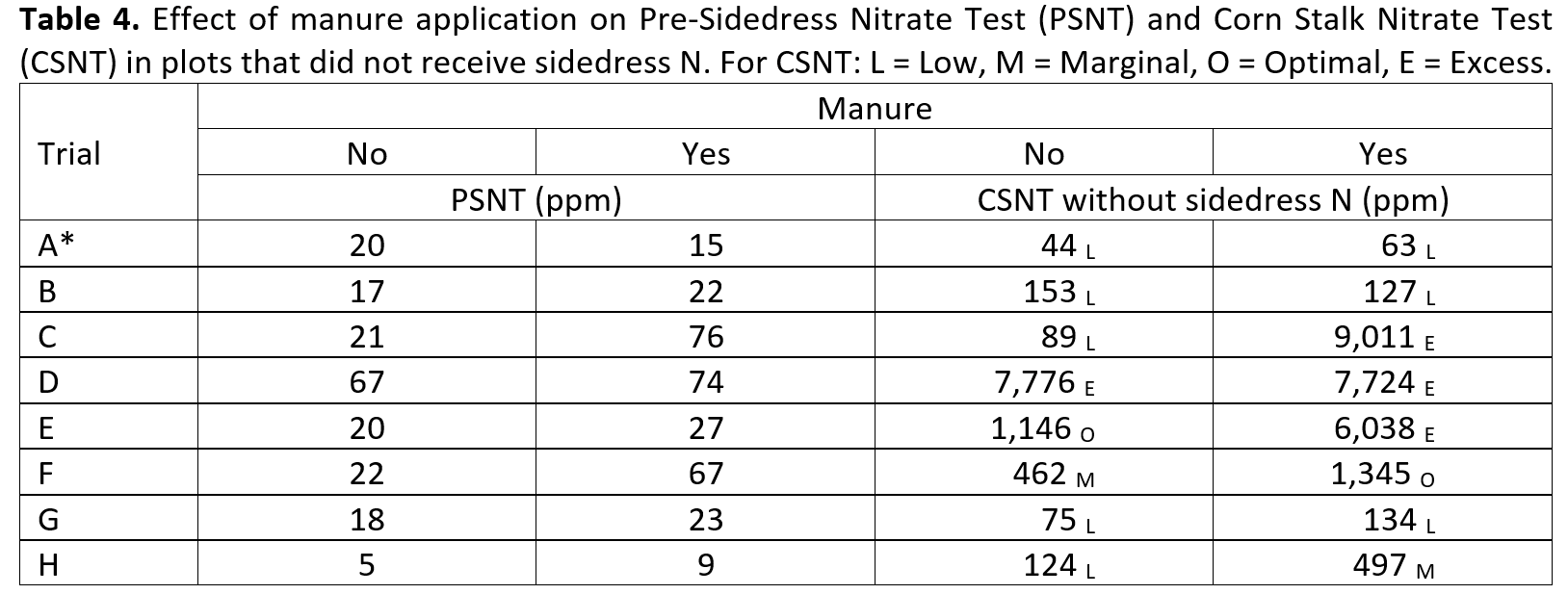

The PSNT levels of the manured plots were higher than their no-manure counterparts for all trials where liquid or digested manure was applied, showing that manure supplied crop available N to the soil (Table 4). In contrast, for farm A the PSNT-N was 15 ppm where compost had been applied versus 20 ppm without compost application, likely due to the high carbon content compared to N content of the compost used in that site. (Table 4). The impact of manure applications was also reflected in CSNT levels (Table 4). For trials D and E, CSNT levels of the plots that did not receive manure or sidedress fertilizer N were optimal or excessive, consistent with the lack of a yield response to N for those two sites. Similarly, for site F, the marginal classification suggested that limited (very little) to no N was needed, consistent with the lack of a manure-induced yield response and minimal fertilizer N response at that site. For the five trials where a crop response to N was determined (trials A, B, C, G, H), the CSNT’s of the zero N plots were low, accurately reflecting the need for additional N. For four trials, the CSNTs where manure but no N fertilizer was applied, were low (trials A, B, and G) or marginal (trial H), consistent with the response to sidedress N in the manured strips. For trials C, D, and E, the CSNTs were excessive in the manure strips without N fertilizer addition, consistent with the lack of a response to sidedress N (MERN = 0 pounds N/acre, Table 3). For trial F, the CSNT of the manured plots without sidedress N application was optimal. This trial showed a small response in yield to the addition of just over 30 pounds N/acre (Table 3).

Conclusions and Implications (and Invitation)

In 2023 we documented “yield bumps” resulting from manure application beyond what could be obtained with fertilizer only in five of the eight trial, consistent with observations for two of the three trials in 2022. For the sites with optimal or high fertility status, this yield increase shows that manure is not just supplying nutrients, but also benefits yield beyond nutrient contributions. The PSNT and CSNT results consistently reflected where N was needed and allowed for documentation of the N contributions of the various manure sources.

The Value of Manure Project will continue in 2024. We will be testing additional manure types and manure application methods in various soil types and weather conditions. Join us in the Value of Manure Project in 2024 and obtain valuable insights about the use of manure in your farm! If you are interested in joining the project, contact Juan Carlos Ramos at jr2343@cornell.edu.

Additional resources

The NMSP Value of Manure Project website and on-farm field trial protocols are accessible at: http://nmsp.cals.cornell.edu/NYOnFarmResearchPartnership/Value_of_Manure.html (project website), http://nmsp.cals.cornell.edu/NYOnFarmResearchPartnership/Protocols/NMSP_Value_of_Manure_Protocol2024.pdf (protocol). Value of Manure phone app: https://valueofmanure-nmsp.glideapp.io/. For the 2022 project results: https://blogs.cornell.edu/whatscroppingup/2023/02/15/manure-can-offset-nitrogen-fertilizer-needs-and-increase-corn-silage-yield-value-of-manure-project-2022-update/.

Acknowledgments

We thank the farms participating in the project for their help in establishing and maintaining each trial location, and for providing valuable feedback on the findings. For questions about this project, contact Quirine M. Ketterings at 607-255-3061 or qmk2@cornell.edu, and/or visit the Cornell Nutrient Management Spear Program website at: http://nmsp.cals.cornell.edu/.