It is hard to believe that three months ago three other interns and I started this internship when the corn was just emerging from the ground and some was not even planted yet. I remember our very first task as interns was to spray-paint dots across the ranges of several fields in the pollinating nursery. We painted a dot at the beginning of each plot so we would know where to go back and plant “delay” plots. These plots were planted later than the majority of the field so all of the corn would not be ready to pollinate at the same time. It was also a way to ensure access to viable pollen later in the season when most other tassels would be done shedding pollen. These delayed plantings were spread out and a few plots were hand planted each day according to how many degree days were recorded in the New Holland area.

We spent our last couple of weeks at the station collecting data and cleaning up from the pollinating season. A lot of time was spent collecting silk and shed dates. To do this, we walked through a field in pairs and recorded when a plot started silking or shedding. Many plots we looked at were one-row plots which made it easier for data collection. A plot was “silking” if at least half of the plants in the plot had ear shoots with silks emerging from them. A plot was “shedding” if at least half of the plants in the plot had tassels currently shedding pollen. We also collected plant and ear height data. Using PVC pipes with inch marks up the side, we recorded both of these heights. The ear height was the height of the plant up to the base of the topmost ear. Plant height was the height of the plant up to the base of the top flag leaf. A considerable amount of this was done at the home farm and at many surrounding locations, just as hoeing and stand-counting had been done two months earlier.

During the last week at Pioneer New Holland, the other interns and I got to go on a field trip with the station supervisor down to DuPont’s headquarters in Wilmington and Newark, Delaware. We saw where a tremendous amount of research is done relating to crop development, protection, and resistance. We were given a tour of the facilities run by a Pioneer team working within DuPont to improve soybean varieties. We saw their office, lab space, growth chambers, and greenhouses. We got to see a much bigger side of the company we had been working for all summer. We heard about how the data we collected in the field was entered into a data collection system that could be viewed by Pioneer researchers at the Delaware facility and at other facilities as everyone collaborated and worked together to create a better product. This information helped to bring our summer work full circle.

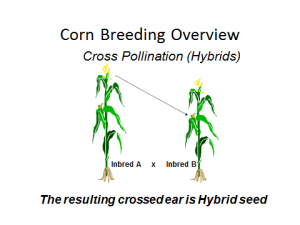

This was a great summer internship in many ways. I would recommend this internship to anybody interested in the research side of a company like Pioneer and also to those who like to work outside. I met great people who are passionate about what they do and who were willing to share what they knew with us. While we spent a lot of time in the corn field collecting data and completing repetitive tasks, it was all necessary for the plant breeders to determine what is working in a new hybrid or inbred, and what is not. I now have a greater understanding as to how a seed research station works for a large company like DuPont Pioneer. I have a deeper appreciation for the amount of time, money, labor, resources, ingenuity, and determination it takes to create a modern corn hybrid.