It’s easy these days to overlook the world around us. When we become so focused on our day-to-day lives, skim our surroundings, often the convenience of everyday items are taken for granted. But, there’s a relentless ability many of us gradually lose overtime: the power to ask how. Start with the kitchen and look in your fridge: how do eggs make it there without breaking? How come bananas have don’t have seeds? How does a pineapple grow? How do they make pasta comes in so many different shapes? I’ll confess, I’m guilty on several counts of failing to wonder how. If you’ve ever spent a few minutes with a 6-year-old child, the power of asking how can quickly escalate into questioning your very existence in the universe. But while we grow up and make the transition into adulthood a certain point is reached, and for many of us, this is when we stop asking how. Instead, we become very irritated when these everyday food items are not available, with little consideration of what goes into their production.

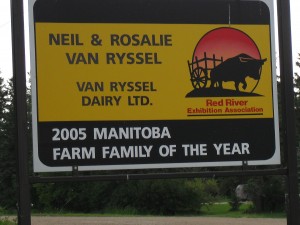

Prior to my internship at Van Ryssel Dairy, I had to come up with a list of what I anticipated to learn from my experience. As would be expected of a pre-vet, my list consisted of mostly ideas that pertained mostly to large animal veterinary practice. I wasn’t let down, and in just two months the amount of practice and experience with treating animals was incredible and extent of the information I took in at times was almost overwhelming. But what really sticks out in my mind when I look over the past few months of my internship at Van Ryssel Dairy, was the realization that even though I have consumed dairy products my entire life I was amazed and a bit embarrassed about how little I actually knew about milk production. And furthermore, I’ll admit, I learned that I grew up my entire life, unknowingly, literally five minutes away from the dairy farm I interned on. While it’s clear that veterinary medicine cannot be overlooked as an important aspect of a dairy, I also saw that it is also just a small part of the entire dairy industry.

This year I’m graduating from Cornell. When I get asked what I am majoring in, I say I’m studying Agriculture Sciences. But the truth is, we are all in agriculture. If you are asking yourself right now “how can we all be in agriculture when something like 1% of all Americans actually still farm today?”, you are on the right track by asking how. Regardless of whether you grew up on a farm or you are you are an agriculture professor, or maybe your from a big city and haven’t taken any agriculture classes at all, we are all in it. The point I’m trying to get across here, is that at some point yesterday, today, and tomorrow you will eat. And just by the act of eating alone, without physically growing your own crops or raising livestock, you have become a part of agriculture. It doesn’t matter how far you live from the farm. It is important to realize that we all have a responsibility to stop before we take the next bite and ask how. I can promise you, you will be absolutely amazed with what you find out. There are a lot of misunderstandings and misconceptions that exist all the way from the farm to the grocery store. In my opinion simply asking how is the most basic way of studying agriculture and becoming a more educated consumer.

As it is my last post for my 2010 summer internship, I would like to thank Peter, Frank, Mel, Michaela, Rosalie, Cara, and Alex for a phenomenal summer at the dairy. I would also like to extend a thank-you to Neil and Rosalie Van Ryssel for allowing me to work on their farm. I look forward to returning in January.

- Rosalie in the milk parlor.