It is hard to believe that summer break has come to an end already, and with that so has my internship at Edgewood Farms, LLC. My last couple days working with the Phelps family was a little change of pace from the normal agronomy work I did the majority of the summer. Three of my last four days at Edgewood consisted of preparing for the 2020 season. Unfortunately, this prep consisted of brush hogging all the organic land that was not able to be planted this spring and had been over run by weeds.  My very last day I was excited about because it was something that I am very familiar with given that I come from a cow-calf farm. My boss, Clayton and I left the farm at 5:30 AM to make the three-hour road trip to Norwich, NY to sort out and load up feeder steers that he was purchasing from an elderly heart surgeon who was selling all his animals. When we arrived at the farm we meet with Phil Trowbridge and his intern, Liz. The first task was to separate all the steers out of a group of over 150 for us to take back to Groveland. After upon completion of that, we sorted out a couple animals we didn’t want and loaded all 70 steers onto a tractor trailer. When the trailer was loaded up and on the road, we helped Phil select 25 of the best looking heifers that he had found a home for along with his bull he had sold to this retiring farmer. Even though the last day wasn’t agronomy related it was something I truly enjoyed and the long car ride gave Clayton and me a chance to recap on the summer and talk about possible opportunities in the future.

My very last day I was excited about because it was something that I am very familiar with given that I come from a cow-calf farm. My boss, Clayton and I left the farm at 5:30 AM to make the three-hour road trip to Norwich, NY to sort out and load up feeder steers that he was purchasing from an elderly heart surgeon who was selling all his animals. When we arrived at the farm we meet with Phil Trowbridge and his intern, Liz. The first task was to separate all the steers out of a group of over 150 for us to take back to Groveland. After upon completion of that, we sorted out a couple animals we didn’t want and loaded all 70 steers onto a tractor trailer. When the trailer was loaded up and on the road, we helped Phil select 25 of the best looking heifers that he had found a home for along with his bull he had sold to this retiring farmer. Even though the last day wasn’t agronomy related it was something I truly enjoyed and the long car ride gave Clayton and me a chance to recap on the summer and talk about possible opportunities in the future.

Something Different and Back to School

Crop Scouting and Planting Cover Crops

The past couple weeks have been pretty routine at Edgewood. I have spent much of my time scouting the farms corn, soybeans, and dry beans. When I was not scouting the crops, I was likely planting oats as a cover crop in all the fields that we unable to be planted this spring due to the extremely wet conditions we experienced.

Scouting has been relatively uneventful lately however; I suppose no news is good news when you are looking for insects and diseases. All the time I spent walking through thousands of acres of corn I found no diseases and only insect pest I found was a patch of western bean cutworm eggs. The eggs are often found on the top side of the upper most leaves and as they hatch the larva quickly move down to the ear,  where they can cause significant damage. An infestation of one cutworm per ear of corn can result in a yield loss of roughly 4% and up to 30-40% if there are several worms per ear. It is recommended that an insecticide be applied if ~5% of the corn plants have either eggs or larva present. Luckily, we never reached a threshold where treatment was necessary.

where they can cause significant damage. An infestation of one cutworm per ear of corn can result in a yield loss of roughly 4% and up to 30-40% if there are several worms per ear. It is recommended that an insecticide be applied if ~5% of the corn plants have either eggs or larva present. Luckily, we never reached a threshold where treatment was necessary.

In dry beans and soybeans, the most common pest found was the red-headed flea beetle. These insects eat the leaves of the plants and the threshold for treatment is based on percent defoliation and stage of the beans. According to North Dakota State University, the action threshold is as follows: 30% defoliation in vegetative stages, 15% in bloom to pod-fill stages, and 25% in pod-fill to maturity stages. The flea beetles in our fields didn’t cause anywhere near this amount of damage so again, like the cutworms in corn, treatment was not needed.

Appley Ever After

Hey y’all, welcome back to the (last) blog. Today I wanted to wrap up my experience at FREC and summarize what I learned.

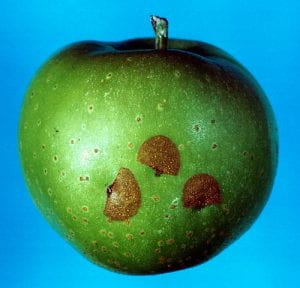

During my time at FREC, I learned the most about general orchard maintenance, such as different pruning methods, tree training methods, how many fruit you should thin down to, and I also learned how to recognize different plant diseases and insect damages. My favorites to find and look at are Plum Curculio damage in apples and Stink Bug gummosis in peaches. I will post pictures below.

In addition, one of my favorite things to do was to test the ripeness of apples with starch iodine. Unfortunately I only got to do this a couple of times because it’s not apple season, but I still had fun the two times that I did do it. The testing was for a color experiment in Gala. I will put pictures of it below. The pictures below are the same treatment, but about a few days apart.

Unfortunately, I was only able to harvest apples once, on my last day. I wish that I had been able to stay there all through apple harvest because that seems so fascinating to me. This is mainly because I would then be able to help with the experiment that Dr. Schupp gave Megan and me. Further, I wished that I was able to work in all of the departments at FREC (entomology, plant pathology, and precision agriculture) because I take interest in all of those areas as well.

I had so much fun at FREC this summer. Most days, it seemed like just hard work, but overall it was very rewarding. I got to do so many cool things like identifying bugs, picking fruit, pressure testing apples and pears, and many other things. Further, I had a fun time writing this blog, it really helped me reflect on my experience at FREC. It helped solidify the knowledge that I gained working there.

Week Ten: Road Trip to North Country

This week I got to spend even more time with extension agents in the field! I drove up to North Country to spend some time with Mike Hunter, a Field Crops Specialist with the CCE North Country Regional Ag Team. Mike led a field day that morning at some of his soybean herbicide plots. Although most weeds are still pretty well controlled by glyphosate, Mike is working hard to develop strategies for farmers to deal with the relatively new challenges presented by herbicide resistant weeds. Tall waterhemp, Palmer amaranth, and glyphosate-resistant marestail are all large threats to crop production in this region of New York State.

Mike took me out to a couple of farmer’s fields to look for possible signs of herbicide-resistant weeds. This soybean field has already been sprayed with glyphosate, but the marestail is is rampant! If the marestail goes to seed, it will be very difficult to control here for years to come.

Maintaining good relationships with local farmers is also an important part of Mike’s work. He has to be able to communicate the results of his own test plots along with other new science in a way that makes sense and is applicable to each farmer that he works with. One example of this is Reed Haven Farms. The farm produces around 1200 acres of crops to feed their dairy herd. Getting to tour their farm gave me an opportunity to see how technology and science can help farms of all sizes.

At Reed Haven, most of the cows are milked by robotic milkers. This cuts down on long term labor costs and volatility, allowing the farmers to focus more on other management aspects of the farm. Pictured here, an alleyway has also been neatly swept by a robotic feed-pusher.

Using laser guidance to attach milk cups to the cow, the robotic milker lowers stress for animals and has helped the farm achieve low somatic cell counts. The cow is able to quickly and comfortably be milked out on her own schedule. Tons of data gets collected from each cow, including the number of chews per day as well as the amount of milk delivered from each quarter of the udder. I posted a video of the milker in action below. The farm currently has 3 milking robots, with the infrastructure in place to add 2 more milkers to their main barn soon.

Fighting a Losing Battle and Trying New Things

This past week, members of the Edgewood Farm team, along with myself, tackled the exciting job of hand pulling waterhemp from a field of snap beans. Waterhemp is in the Amaranth family which also includes other commonly found pigweed species. Because it is a relative of pigweed, it can often be difficult to distinguish between the different species, especially as seedlings. As waterhemp matures it becomes a little easier to identify because mature plants tend to have glossy and elongated leaves. You might be wondering why we had to pull it by hand. Unfortunately, waterhemp is resistant to many of the herbicides on the market today and that surly seems to be the case here since it was unphased by last years and this year’s herbicide applications. Left unchecked the waterhemp would quickly spread out of control because a single plant can produce upwards of one million seeds.

On a more exciting note, wheat harvest is finally under way in Western New York. As a bit of an experiment, a field of wheat was intercropped with soybeans for the first time at Edgewood. Instead of planting the wheat with a grain drill, as is conventionally done, they planted it with their twin-row planter. Then in May, the same twin-row planter was used to plant soybeans in between the rows of wheat. Last Thursday, the combine headed to the field to harvest the wheat and it yielded surprisingly well considering how poor it looked earlier thus year (lots of winter kill and drowned wheat). Even though I will be back in school when soybean harvest takes place it will be exciting to hear how they turn out. I imagine I will see more cropping systems like this in the future from Edgewood if this goes well and on paper it looks like it will return the largest profit per acre of all their crops.

Week Nine: Work with Extension

This was one of my favorite weeks field-work wise. I got to drive out to meet with Jodi Putman, a Field Crop Specialist with the Northwest New York Dairy, Livestock & Field Crops Team. Jodi stays incredibly busy. She works full time with CCE as well as taking classes and doing research through a Cornell graduate student program. I got to hear her talk about some of the history behind sulfur availability in the United States as well as current soybean crop needs at the Musgrave field day earlier this year, so it was really exciting to see more of her plots in action.

Jodi and Josh, the new Field Crops and Forage Specialist with the Southwest New York Dairy, Livestock, and Field Crops Program, also took the time to give me some weed ID lessons in the field. Sedges have edges!

We started out the day sampling soybean trifoliates to be tested for sulfur content. It is very important for crops to have the right balance of essential nutrients available to try and avoid literally any shortage during the growing season. If plants have the right amount of each nutrient available at the right time of the year, not only will yields increase but possible nutrient losses are also greatly decreased. If soybeans don’t have enough sulfur at key points in the growing season, even large amounts of other nutrients will not be able to be used by the crop.

To sample soybean trifoliates, we picked the youngest fully developed leaves off of the plant. We sampled around 20 plants per plot. There were 4 treatments and 4 replications, so in total we sampled over 300 plants in one field alone.

Jodi also took me out to a local farmer’s field to see some possible European Corn Borer damage. The farmer didn’t plant the field with Bt treated seed, so the corn was genetically vulnerable to ECB attack. This kind of scouting is a big part of Jodi’s job. The farmer needed help figuring out how much of the corn was damaged and whether or not it was worth using a chemical to treat the corn this late in the season. Although a lot of damage was already done, Jodi was able to give some advice to help avoid future infestation.

Peachy Keen

Hey y’all, welcome back to the blog. This week, I wanted to talk about a peach experiment that I briefly mentioned in my last blog post. These peach trees were planted in 2014, so the block of peaches is aptly named “P14”. The experiment is a rootstock trial that spans a three year period and this is the last year they are collecting data.

The peaches are planted on about five different rootstocks, such as Bailey and Lovell. Additionally, they are all the same variety: Coral Star. There are five rows of peaches in this experiment, each row being 79 trees long, with only one guard row due to some technical difficulties in orchard planning. The trees were grown in a Quad V formation, meaning that they have two scaffolds per side, creating four scaffolds.

In regards to experiment set-up, each plot of trees was five trees, and each row was a new replicate. From the five trees in each plot, only the best two were data trees.

In order to maintain good orchard maintenance, like most trees, these needed to be pruned. Megan and I were given this task at the beginning of June and worked on it on and off until the first of July, so it felt like it took and eternity. In addition, the trees are so tall, that we needed to prune them from the ground and we also needed to use the N. Blosi, which is a scissor lift platform, but with an expanding platform on either side. Needless to say, Megan and I were (very) relieved when we finished. Below, I will put some pictures of some of the cool creatures we found while pruning.

To add to the fun, nutrient samples needed to taken from the leaves and soil. To collect the leaves, I was sent out to pick fifty leaves from waist to top-of-hand height from mid-shoot from each plot. I then put them in correctly labeled brown paper bags and put them on a greenhouse bench to dry out. For the soil samples, I had to collect a sample from each tree in the plot, put them in a bucket, mix them together, and scoop about two cups worth into another correctly labeled brown paper bag. They were also put in the greenhouse to dry. The sad thing about that step was that some of the soil was too heavy for the brown paper bags and they ripped. I had to go collect more samples. It was not a good day in my book. A couple weeks later, the samples were taken up to Penn State Main Campus and they had nutrient testing done on them.

Then, on August first, we did our first harvest. The peaches were picked into correctly tagged crates and then we ran them through our grader, which counts, weighs, and categorizes them. Then, the data is collected and the peaches are packaged for sale. Our second harvest, which was our largest, was done on August fifth. Unfortunately, our grader broke and the counts, weights, and measures had to be done all by hand. It was torturous work. Luckily, I had already scheduled two days off, so I got to miss that load of fun. The third harvest was done on August ninth, Most of the trees had been stripped in the second harvest, so it was the easiest to pick. By then, the grader had been fixed and we were back in business. This completed the seemingly never-ending arduous task of P14, but it was quite rewarding in the end.

In my next (and last) blog post, I wanted to sum up my experience at FREC and everything I have learned this summer.