Olivia Godber1, Mart Ros1, Agustin Olivo1, Kristan Reed2, Mike van Amburgh2, Kirsten Workman1,3, and Quirine Ketterings1

1Nutrient Management Spear Program, 2Department of Animal Science, 3PRODAIRY, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853

Introduction

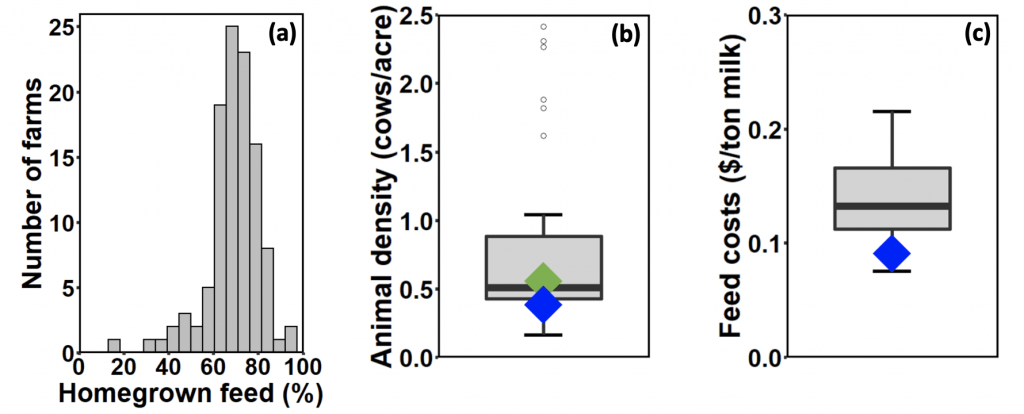

Between 2017 and 2019, 110 New York dairy farms completed their whole farm nutrient mass balance assessment. Of the feed fed to the animals on the farms, almost 70% was homegrown, which means it was produced on the land-base operated by the farm itself (Figure 1a). Almost all this homegrown feed was forages such as corn silage, alfalfa, and grass. The farms averaged 0.56 mature cows per acre (weighted by tillable acres). How does this compare to average values in the United States and why is this important?

Comparison with Dairies in New York and Nationally

The share of homegrown feed for the New York farms was considerably high than typically reported across the US. The number of mature cows per acre was higher across the US (Figure 1b), while farmers in the assessment spent considerably less on feed costs per unit of milk produced than reported for the US (Figure 1c).

Importance of Optimizing Homegrown Forage Production

For most dairy farms, feed purchases are the largest annual expense, so growing forages on the farm’s land base reduces the costs of feed. However, there are also other reasons why optimizing homegrown feed is key.

For most dairy farms, feed purchases are the largest annual expense, so growing forages on the farm’s land base reduces the costs of feed. However, there are also other reasons why optimizing homegrown feed is key.

-

- Reducing the amount of feed that needs to be imported helps to avoid the carbon and energy footprint that imported feeds have (production elsewhere plus transport to the farm).

- By minimizing feed imports, farms are also minimizing the risk of feed price fluctuations and economic uncertainty.

- Farmers that grow feed have greater control over the quality of that feed. They can select what crops are needed and in which quantities to meet the needs of their animals.

- Farmers can, to a certain extent, alter crop management practices as needed, and optimize nutrient use, thereby reducing nutrient losses to the environment.

- By increasing nutrient recycling with the use of manure on the farm itself, farms are reducing their reliance on fertilizer use. This results in a smaller environmental footprint for feed production. Optimizing the use of manure over synthetic fertilizer can also help with managing volatile fertilizer prices and with the farm’s overall economic sustainability.

- Farms with insufficient land base will need to export manure. By optimizing feed production and animal density, a farm can reap the benefits of using manure, thereby avoiding extra expenses incurred with manure export (if feasible at all) and avoiding carbon emissions associated with the transport of manure beyond the farm boundaries.

Acknowledgements

We thank the farmers, farm advisors and past and current NMSP team members who worked on the whole farm NMB project with us over the past 15+ years. This research is funded primarily by a gift from Chobani, in addition to Federal Formula Funds, and grants from the Northern New York Agriculture Development Program (NNYADP), Northeast Region Sustainable Agriculture and Education (NESARE), New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYDEC). For questions, contact Quirine M. Ketterings (qmk2@cornell.edu) or visit the Cornell Nutrient Management Spear Program website at: http://nmsp.cals.cornell.edu/.