Why study weeds?

Organic farmers have indicated that weed competition is a major concern. Although spraying and tillage are two methods of managing weeds, we wanted to explore reducing weeds’ competitive ability through an ecological framework. Previous research suggests that crops are more competitive against weeds (ie. more able to “tolerate” weeds) in organically managed compared with conventional growing systems. Many factors may contribute to this pattern, including plant resource-partitioning abilities, plant-microbe associations, and other ecological relationships.

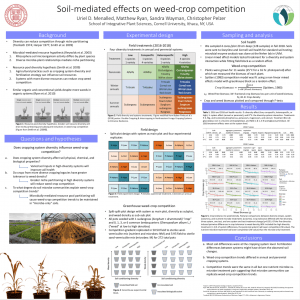

Experiment: Soil-mediated cropping diversity effects on weed-crop competition

Does system diversity influence weed pressure?

Diversity in a cropping system (meaning, more different kinds of plants growing together) can influence soil resources, and systems with more diverse resources may have reduced plant-to-plant competition because of niche partitioning. Niche partitioning refers to how competing species use different resources and thus are better able to coexist. Can agricultural practices that increase diversity decrease weed competition on the crop?

The greenhouse weed-crop competition project

The goal of this project was to explore the ecological mechanisms of crop-weed competition by linking crop yields to soil physiochemical properties. We studied crop tolerance to weed pressure across a range of soils conditioned with different levels of cropping diversity. We used field soil, and sterile greenhouse soil inoculated with the microbial communities of each field soil sample in pots in a greenhouse. By using both field soil and inoculated soil, we hoped to find indications of soil biota establishing biodiversity-mediated crop-weed competition in the pots.

The soil came from a field experiment planted with an annual cropping system and a perennial cropping system based on species local dairy farmers would typically plant for forage. There were four levels of diversity: “Low” (1 variety of 1 species), “Conspecific” (4 varieties of 1 species), “Heterospecific” (4 species with 1 variety of each), and “High” (4 varieties of each of 4 species).

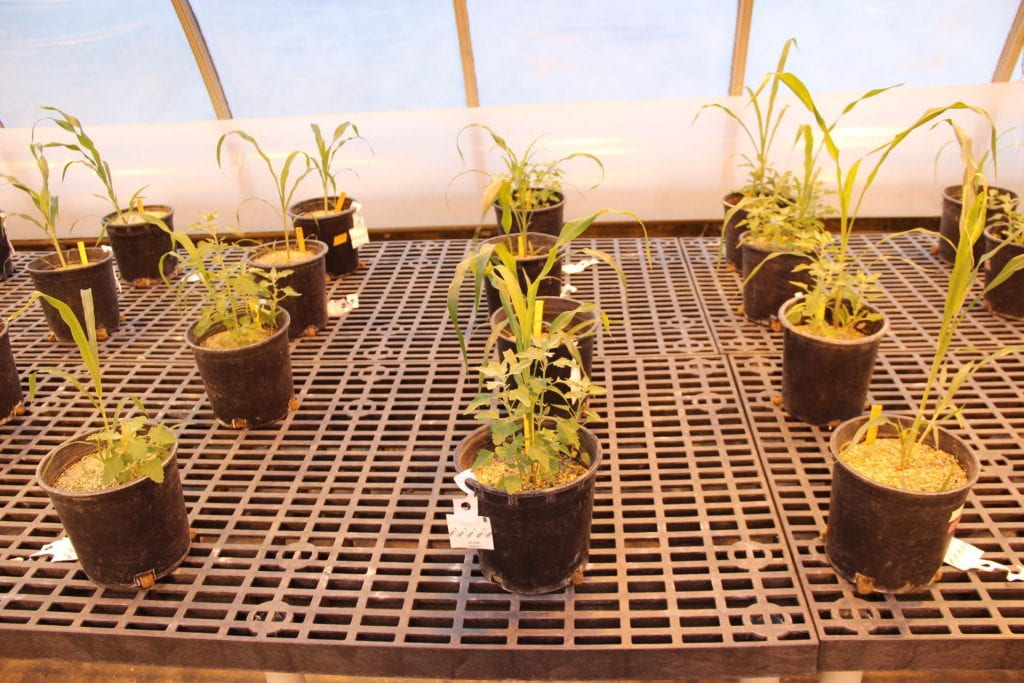

Pots were filled with soil from the annual and perennial systems under the four levels of diversity. Some of the pots had field soil, some had sterilized potting mix that was inoculated with biota from the field soil, and some had sterilized soil that was not inoculated (the control). Then we planted one crop plant seed (sorghum sudangrass) and different densities of weed seeds (common lambsquarters). After eleven weeks in the greenhouse, we harvested the crop and the weeds and weighed them.

The pots with field soil had the nutrient and microbe footprints of the crop diversity treatments, while the inoculated pots maintained constant fertility and mostly differed in their soil microbe communities. These two potting treatments allowed us to study the relative importance of soil microbes in defining weed-crop competition.

Results

We learned that most differences in crop tolerance to weeds were due to diversity. In pots that had soil from a more diverse cropping legacy, weed-crop competition was higher. Across all diversity levels and sources of soil, competition trends were the same in all but one instance. This means that the microbe-inoculated sterilized soil showed the same trends as the field soil, which suggests that microbe communities can replicate weed-crop competition trends.