Ashley Bound1, Emily Anderson2, Erik Smith1

1CCE Central NY Dairy, Livestock, and Field Crops Team

2CCE Chenango County

Introduction

Potato leafhopper (PLH) is a major pest to alfalfa crops across the US and in Central New York. It causes damage to young plants and successive regrowth, resulting in a decrease in overall quality with the potential to cause financial losses to farmers. With funding from the Chobani Community Impact Fund and leadership from the Central New York Dairy, Livestock, and Field Crops (CCE CNYDLFC) regional team and Cornell Cooperative Extension of Chenango County (CCE Chenango), local Future Farmers of America (FFA) chapters worked together during the 2023 growing season to inform farmers about PLH population dynamics in their fields. The goal of this project was to monitor alfalfa fields for PLH, inform farmers if and when PLH populations had reached the action threshold (the population at which a farmer would want to take action to prevent economic loss) and gain a better understanding of the populations of potential insect predators of PLH through the growing season. In the process, community members of different ages and backgrounds had the opportunity to come together to gain hands-on experience with agriculture in the region, share skills and unique perspectives, connect with farmers, and participate in a local citizen science project.

Alfalfa is a good source of protein for livestock and a high-yielding crop for silage, hay, and pasture, and is an essential component of Total Mixed Rations on most dairy farms. Alfalfa is also useful in crop rotations because its root systems help improve soil structure and, as a legume, it is able to fix nitrogen from the atmosphere.

One of alfalfa’s most common pests in New York is potato leafhopper (Empoasca fabae) (PLH) (Fig. 1). Heavy PLH pressure can result in the reduction of stand quality and the loss of nutritional value, and it can impact the availability of successive cuttings. PLH is found across much of the eastern half of the United States and is a pest of many different crops, including clovers, potatoes, soybeans, and apples. At ¼ in, the small PLH can cause big problems. It feeds by using its straw-like mouthparts to extract sap from plants. While taking nutrients from the plant, the PLH also secretes a toxic saliva, which reduces the plant’s ability to photosynthesize. Leaves of infected plants will begin to yellow; this is known as “hopper burn” (Fig. 2).

Potato leafhopper management

PLH pressure in alfalfa fields is commonly addressed in two ways: spraying the field with a pesticide to reduce PLH numbers or harvesting the field early. Costs and benefits exist between both options, but often the decision relies on the timing of the upcoming harvest.

Advising between when to cut and when to spray pesticides can help the farmer reduce the cost of pesticides, fuel, and labor used while also maintaining the value of the alfalfa stand.

Farmers and pest scouts use large canvas sweep nets to sample PLH populations in alfalfa fields (Fig. 3). If the field has high PLH numbers, but the farmer is within one week of harvesting the field anyway, it would be more cost-effective to cut the field early. Cutting early allows the farmer to prevent further damage caused by PLH and maintain the quality of the alfalfa without unnecessarily expending time, fuel, and product by spraying with a pesticide. On the other hand, if the field is more than one week away from harvest and PLH numbers are high, it would make more economic sense to treat the field with an insecticide to provide the alfalfa more time to mature without PLH damage, since a low-yield harvest would have low economic value.

It is unclear whether PLH populations are predated upon by other insects or spiders to a degree that would affect alfalfa yield loss. Several species are reported to feed on PLH, but PLH are considered too fast to be captured by most predators. Still, insecticide applications intended to manage PLH would potentially affect other insects in the field, including those predating on pea aphid, another summertime insect pest of alfalfa that can cause yield loss in rare cases where populations get out of hand.

What is considered a high PLH number?

Table 1. Economic thresholds of PLH in non-PLH-resistant alfalfa (adapted from Cornell Guide for Integrated Field Crop Management)

| Height of Alfalfa (in) | Max PLH/Sweep |

| <3 | 0.2 |

| 3-7 | 0.5 |

| 8-10 | 1 |

| 11-14 | 2 |

| 15+ | 2* |

* No action needed if within 1 week of cutting, and consider cutting early.

For Example…

If the stand of alfalfa is 21 in. tall and the average number of PLH per sweep was 2.5, then the action threshold has been reached, and it would make sense to cut the stand early to prevent further damage because it is likely within one week of harvest.

However, if the alfalfa in the field is only 10 in. tall and an average of 1.5 PLH were found per sweep, the field should instead be managed with an insecticide application to prevent further PLH damage, since the next cutting will not happen within the next week.

If the alfalfa height is 20 in., but the average number of PLH per sweep was only 1.2, then the action threshold was not reached, and no action would be warranted for the field.

Methods

To help our extension staff collect data and provide management recommendations to local farmers, nine area youth groups including seven FFA chapters were provided with sweep nets, insect identification guides, and a comprehensive insect identification textbook, all of which they could keep at the end of the project. In-person training sessions and data sheets were also provided by CCE staff.

Data collection was performed with a standard 15-inch-diameter insect sweep net (Fig. 3). Participants swept the net a total of 10 times back and forth in a swinging motion while walking forward – each swing counting as one sweep – and at the end of the 10 sweeps, the number of insects in the net was recorded. In addition to PLH, participants also recorded seven types of predators that are known to feed on PLH and other insect pests. These included hoverfly larvae (Fig. 4), ladybugs and ladybug larvae (Fig. 5), lacewing larvae, damsel bugs, assassin bugs, minute pirate bugs, and spiders (including harvestmen, also known as daddy longlegs).

This process was repeated for a total of three – five sets of sweeps, or 30-50 total sweeps per field. Fields were typically re-sampled weekly through the growing season, except immediately following harvest.

After counting the numbers of pests and predators and averaging those values across all sweeps, alfalfa height was recorded so that a determination could be made as to whether that field reached the threshold for management using the established economic thresholds (Table 1).

Results and Discussion

With four FFA chapters and one local youth group participating through the duration of the project, we were able to monitor PLH in 21 alfalfa fields on 13 farms in 5 counties over 12 weeks from June to August, when alfalfa crops are at highest risk of PLH and when producers are most likely to invest in insecticidal sprays to salvage yield.

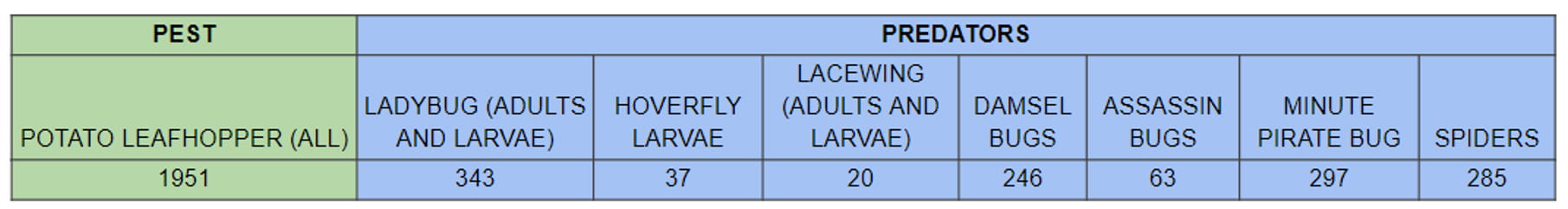

Across all fields and sampling dates, 1,951 PLH and 1,291 insect predators were recorded (Table 2). This does not include many other insects that were also observed in our sweep nets, like horse flies, deer flies, bees, aphids, and parasitoid wasps. The two most common insects sampled were aphids and several species of parasitoid wasps. Aphid populations seldom reach damaging levels in alfalfa, and these species of wasp parasitize other insects, primarily aphids in this setting.

Table 2. Total PLH and selected predators observed across all fields and dates

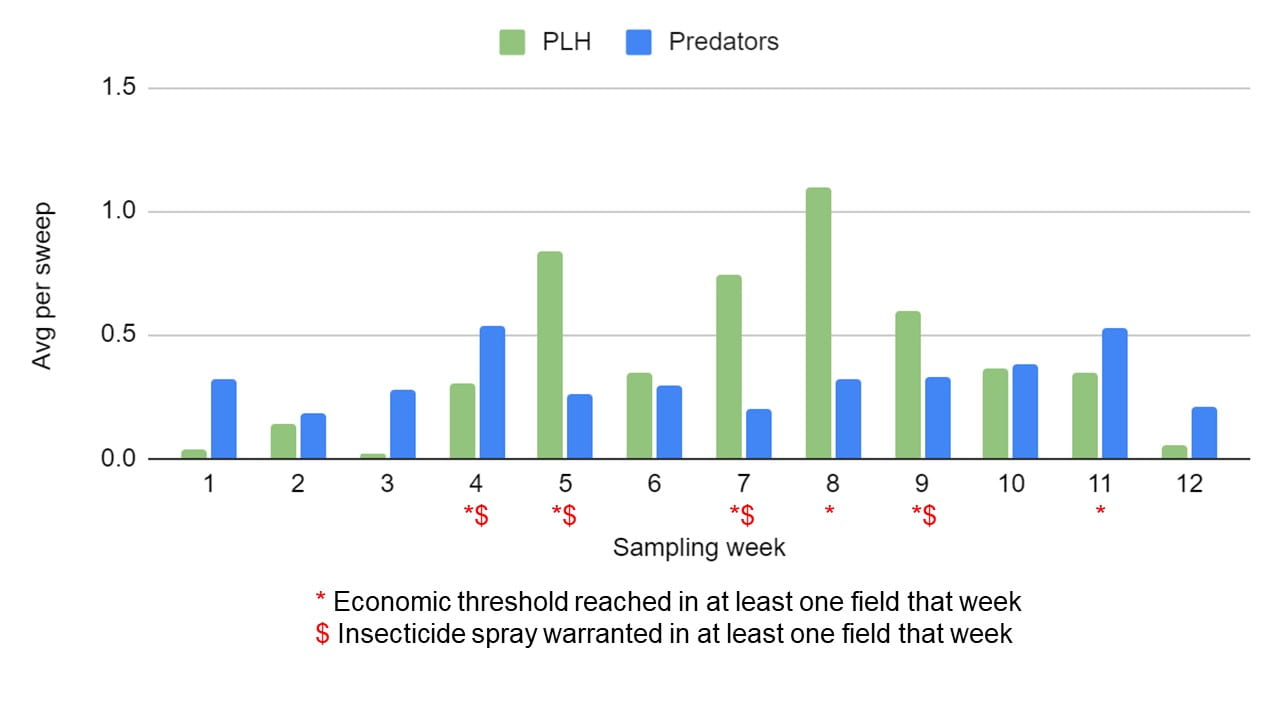

Out of 126 sampling efforts, the action threshold was reached only 10 times (7.9%). Of those 10 times, applying a short-residual insecticide was the most economical management strategy in five cases, while early harvest was recommended the other five times. This meant that it was only economical to spray in 3.97% of cases. Only eight fields of the 21 monitored during the growing season reached threshold at least once (38% of fields). Five of those eight were fields where early harvest was recommended due to being within one week of planned harvest. Interestingly, of the three fields where sprays were recommended due to reaching threshold more than a week from harvest, two were in this situation more than once during the season (twice each). This means that only very few fields experienced consistently high PLH pressure. These fields will be monitored in 2024 to see if these trends continue, or whether 2023 was unique. Without question, PLH populations can vary wildly between growing seasons due to their migratory nature, so more observation will be needed to see how different fields experience PLH pressure over time.

Predators outnumbered PLH in our sweeps until mid-July, and again after mid-August (Fig. 6). We know that the predators we recorded have been reported by others to feed on PLH, but we do not have a good understanding of how well they may be able to control PLH populations. But if they are, and if 2023 was a typical year for these species, there appears to be a period of about 5 weeks in the middle of summer that may be the highest risk for yield loss due to PLH infestation and potential yield loss. Alfalfa weevil is an important pest of alfalfa through late-June, and these predators may be exploiting this pest before PLH populations increase.

Forage crops are unique because they are harvested multiple times per year, allowing for a partial reset of local pest populations with each harvest. But while the recommended short-residual sprays do not have extended activity directly, their effects can extend through the growing season if used incorrectly. Spraying without scouting to verify whether action thresholds have been reached, and spraying when pests are below economic thresholds not only wastes money in the short-term, but puts important insect diversity at risk. Not only non-target insects like pollinators, but also predators that may be feeding on PLH, alfalfa weevil, and aphids and preventing their populations from reducing forage yield and quality.

Potato leafhopper-resistant alfalfa varieties exist, and the economic thresholds of these varieties can be double, to nearly 10x the level of traditional alfalfa. If PLH-resistant varieties were used in this study, the economic threshold would have been reached no more than three times, all in different fields. For resistant varieties with economic thresholds higher than 3x the standard varieties, no fields in our study would have reached the economic threshold. However, farmers usually prioritize digestibility or other desired traits over pest resistance when choosing an alfalfa variety (these traits are not stackable with current varieties), so most alfalfa grown in NY is not PLH-resistant.

The partnership between CCE Chenango, the CNYDLFC regional team, and FFA chapters was instrumental to the project’s geographic reach and success. Through this partnership, young people in the community were able to aid farmers while learning about local agriculture, entomology, Integrated Pest Management, and the natural diversity that can be found on farms. While many of the young people involved with this project either lived on farms or were otherwise related to farmers, this was an enriching experience that gave them a better understanding of how crops are produced, and how farmers and CCE work together to make informed management decisions.

Additional Resources

Acknowledgments

This project was made possible by Chobani through the Chobani Community Impact Fund and relied on leadership and participation from the Central New York Dairy, Livestock, and Field Crops team; Cornell Cooperative Extension of Chenango County; high school members of the local Future Farmers of America chapters; and each landowner that generously allowed sweeping to occur on their fields. The authors thank Joe Lawrence (PRO-DAIRY) and Ken Wise (NYSIPM) for reviewing the article. For questions, contact Erik Smith, erik.smith@cornell.edu.