Project Leaders

Bryan Brown, NYS IPM Program

Venancio Fernandez, Bayer Crop Sciences

Mike Hunter, Cornell Cooperative Extension

Jeff Miller, Oneida County Cooperative Extension

Mike Stanyard, Cornell Cooperative Extension

Cooperators

Derek Conway, Conway Farms

Jaime Cummings, formerly NYS IPM Program

Quentin Good, Quentin Good Farms

Antonio DiTommaso, Cornell University

Michael Durant, Lewis County Soil and Water Conservation District

Scott Morris, Cornell University

Ali Nafchi, Cornell Cooperative Extension

Ryan Parker, NYS IPM Program

Jodi Putman, Cornell Cooperative Extension

Joshua Putman, Cornell Cooperative Extension

Matthew Ryan, Cornell University

Lynn Sosnoskie, Cornell University

Ken Wise, NYS IPM Program

Funding Sources

New York Farm Viability Institute

Project Location

Trial locations in Seneca County but results are likely applicable statewide.

Abstract

Herbicide resistant tall waterhemp (Amaranthus tuberculatus) continues to be one of the most problematic weeds in US field crops. Thus far, it has primarily established in western and central New York. Our second year of trial results generally followed our first-year results. Herbicides in WSSA groups 2, 5, and 9 should not be relied on for waterhemp control. However, programs that included at least two non-chemical tactics or herbicides from groups 4, 14, or 15 were very effective. Seedbank modelling showed that control at 95%, 98%, or 100% would cause waterhemp emergence to increase, maintain, or decrease over time, respectively. Our partial budget analysis showed that profitability generally reflected yields. We also found that cereal rye (Secale cereale) residue can provide up to 87% control of waterhemp, which, if used in conjunction with a moderately effective herbicide program, could provide excellent control.

Background and Justification

Herbicide resistant waterhemp has been reported in many western and central NY counties. Soybean farmers have reported yield losses of 50% due to this weed, even after herbicide applications. Our greenhouse spray chamber tests and field trials from 2019 suggest resistance to WSSA herbicide groups 2, 5, and 9 (ALS inhibitors, photosystem II inhibitors, and EPSPS inhibitors, respectively). Our most effective control programs in 2019 relied on herbicides from other groups as well as additional physical or cultural tactics.

Waterhemp in other states has also developed resistance to different herbicide classes, including WSSA groups 4 and 14 (http://www.weedscience.org/Pages/Species.aspx). These groups include dicamba, 2,4-D, Valor, and Cobra. Resistance to these additional herbicides would make successful waterhemp control even more challenging.

Overwintering cover crops such as cereal rye can be sprayed or rolled-down to provide a weed suppressive mulch prior to soybean planting. In NY, Pethybridge et al (2019) showed that rolled rye achieved very effective suppression not only for weeds, but also for white mold. Furthermore, waterhemp and another problematic herbicide resistant weed in NY, called horseweed or marestail (Conyza canadensis), both have very small seeds that lack the stored energy to emerge through deep soil or mulch.

Objectives

Objective 1. Continue to evaluate the effectiveness of several different programs in controlling waterhemp in soybeans.

Objective 2. Assess the potential for rye cover crop mulch to suppress waterhemp emergence.

Procedures

Objective 1.

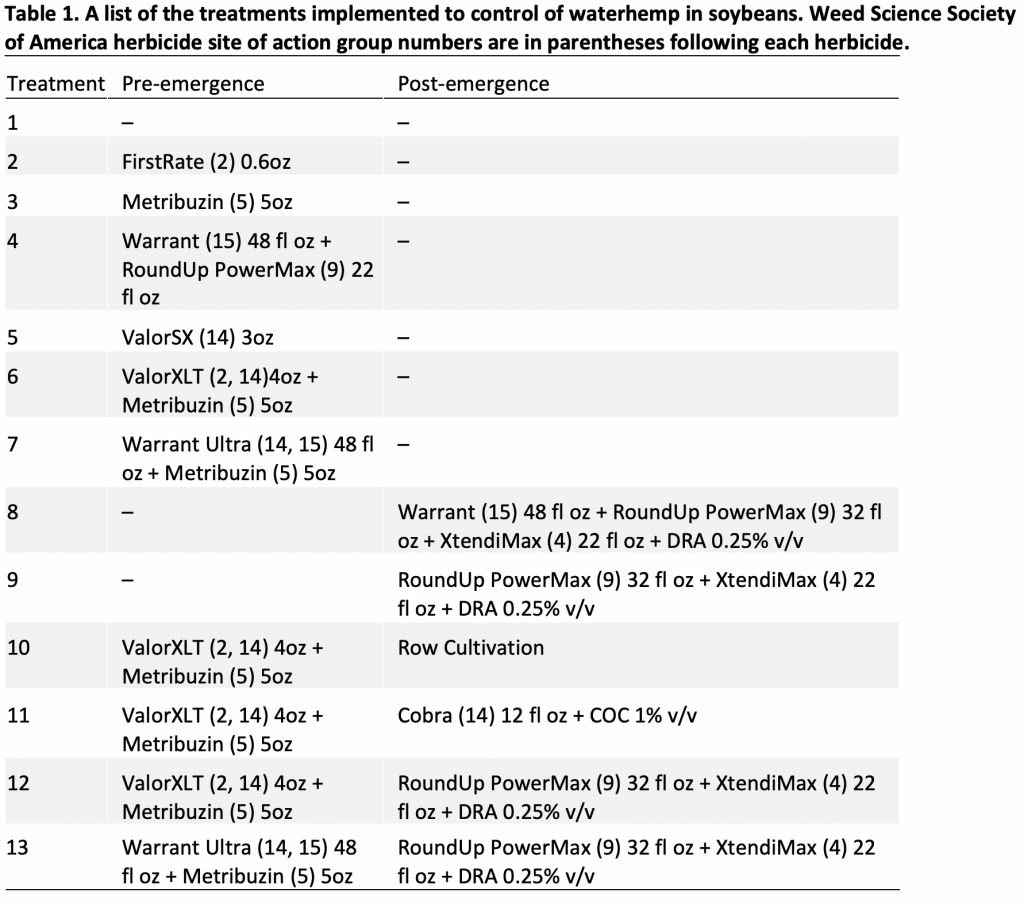

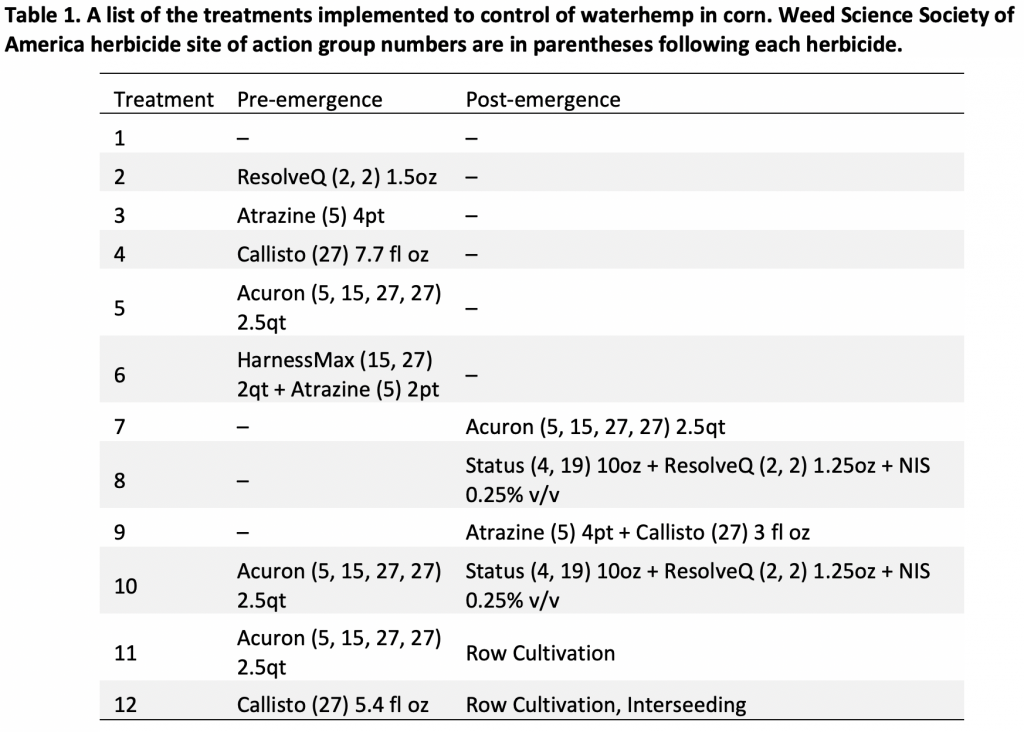

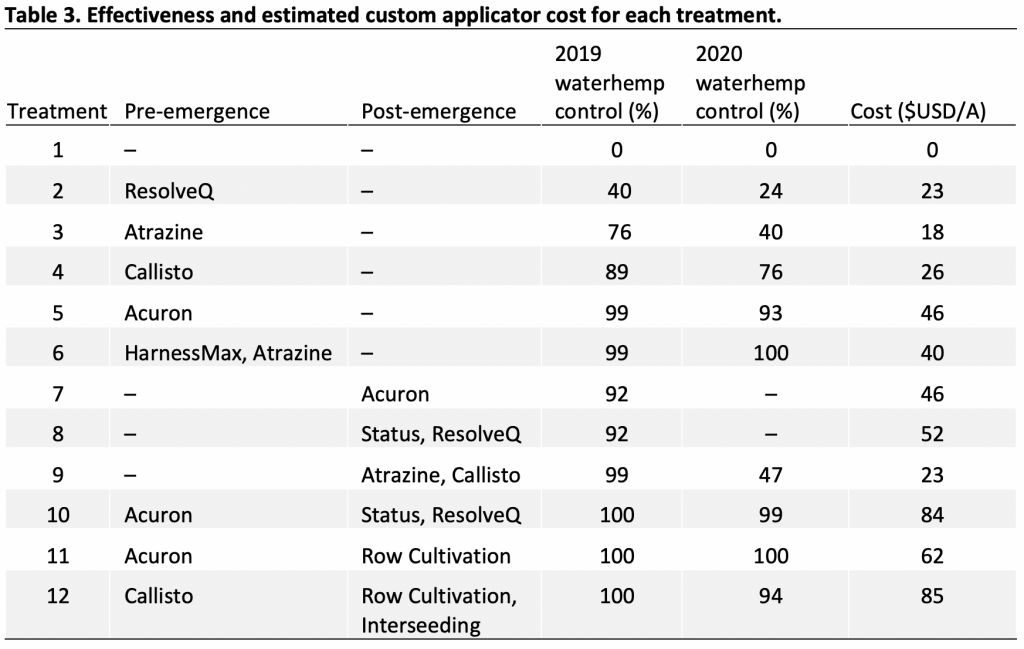

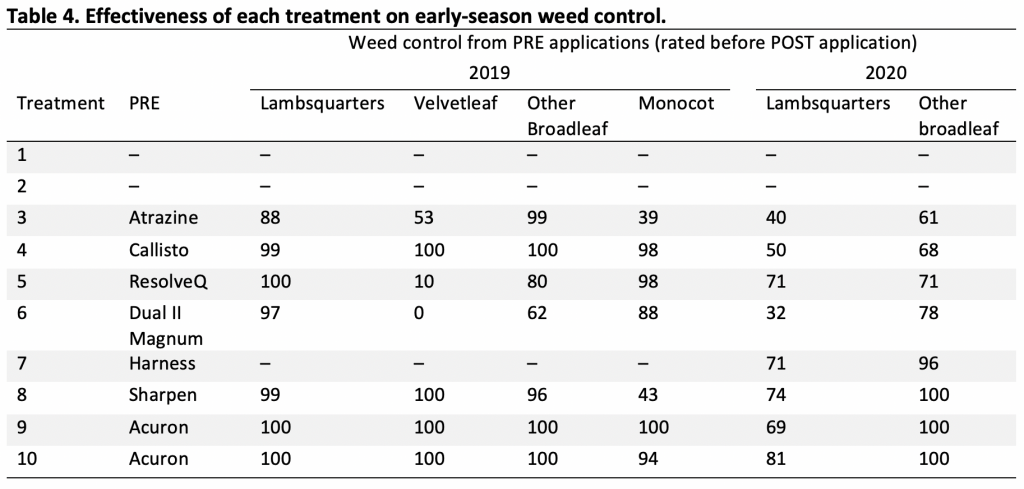

The trial site was in Seneca County, NY on a field of Odessa silt loam soil where waterhemp had survived various herbicide applications and produced seed in 2018 and was moderately controlled in 2019 in corn. In 2020, the ground was prepared for planting with a field cultivator on May 5 and planted on May 6. Pre-emergence applications were made after planting on May 8. Cultivation occurred on June 16 while the other post-emergence treatments were applied on June 18. All treatments are listed in Table 1. For fertilizer, DAP (10-46-0, 20 lbs N/A, 92 lbs P2O2/A) and muriate of potash (0-0-60, 125 lbs K2O/A) were applied prior to tillage and UAN (32-0-0, 30 lbs N/A) was applied at planting.

Plots were 25’ long and 10’ wide. Each treatment was replicated four times in a randomized complete block design. Spraying was conducted using a backpack CO2 sprayer with a 10’ boom. Spray volume was 20 gal/A applied at 40 psi. Row cultivation was achieved using a Double Wheel Hoe (Hoss Tools) with two staggered 6” sweeps (12” effective width). Two passes were made per row so that 24” of the 30” rows were cultivated.

Weed control was assessed August 15-22 by collecting all aboveground weed biomass within a 2 ft2 quadrat. The quadrat was used four times per plot, placed randomly in the two middle rows of each plot. Weeds were placed in paper bags and dried at 113 degrees F for 7 days, then weighed. Control was calculated by subtracting the biomass of each treated plot from biomass of the untreated plots, dividing by the biomass of the untreated plots, and multiplying by 100. Waterhemp was the dominant species present in this trial. Other species did not provide enough data for comparison. All waterhemp was manually removed immediately after the weed control assessments in order to prevent seed production.

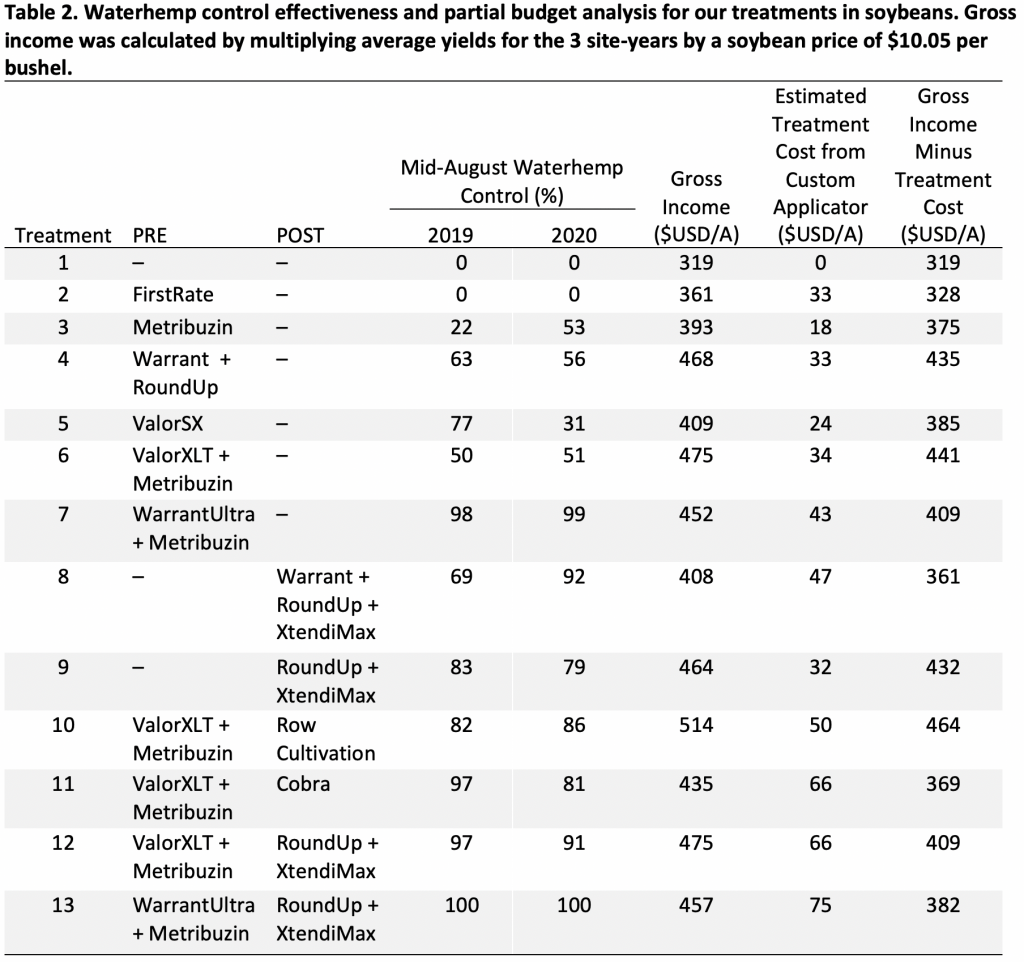

Soybean yield was measured in mid-October by hand harvesting 20-row-feet from the two middle rows of each plot. In our partial budget analysis, gross income was calculated by multiplying the average yield per treatment across all sites for 2019 and 2020 by a soybean price of $10.05 per bushel (Langemeier 2018). Weed treatment costs were estimated based on personal communications with several local custom applicators.

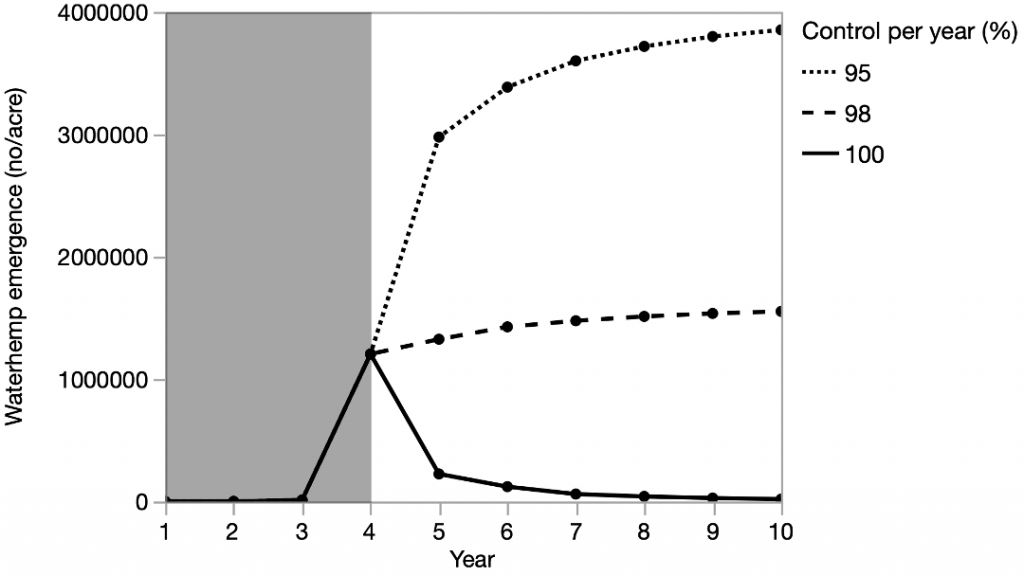

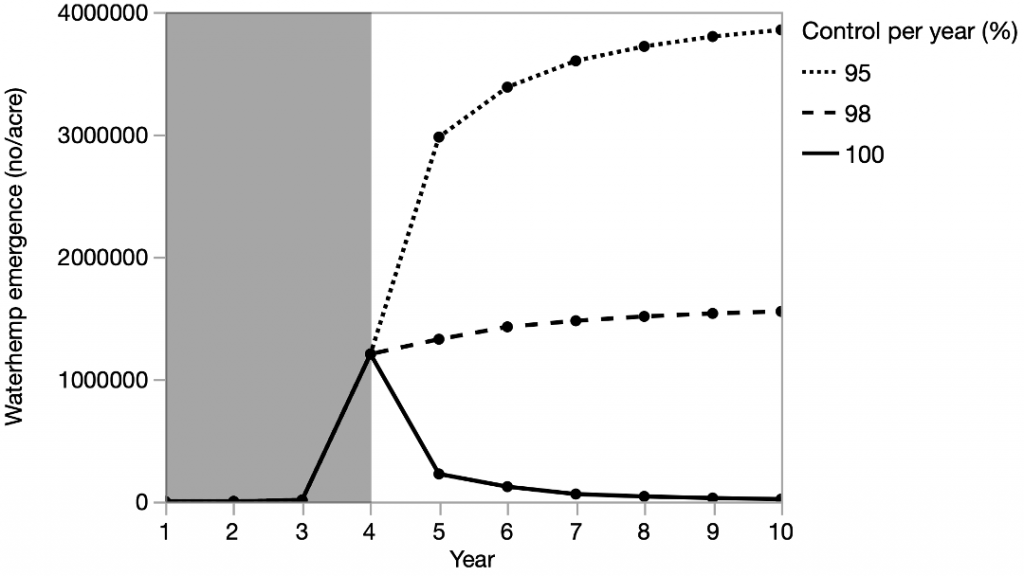

To illustrate the effects of allowing waterhemp to produce seed, we produced a 10-year model of waterhemp emergence based on the number of seeds in the soil. The model was created based on observed waterhemp emergence and biomass production in 2019 and assumed a preceding three-year period of uncontrolled growth. We also assumed that 8% of the seedbank would emerge each year (Davis et al. 2016) and that for a given cohort, viability was reduced by 81% after one year, reduced by an additional 50% after years two and three (Heneghan and Johnson 2017), and reduced by 32% each subsequent year (Davis et al. 2016). We also assumed waterhemp would produce 441 seeds per gram of biomass (Heneghan and Johnson 2017) with a maximum waterhemp biomass of 386 g/m2 based on our results.

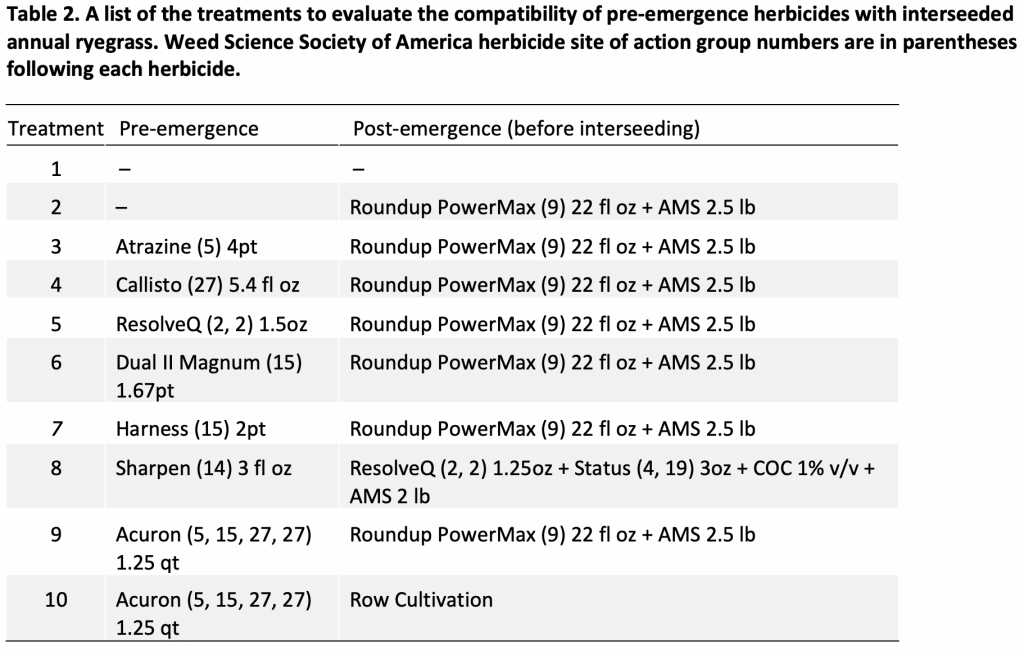

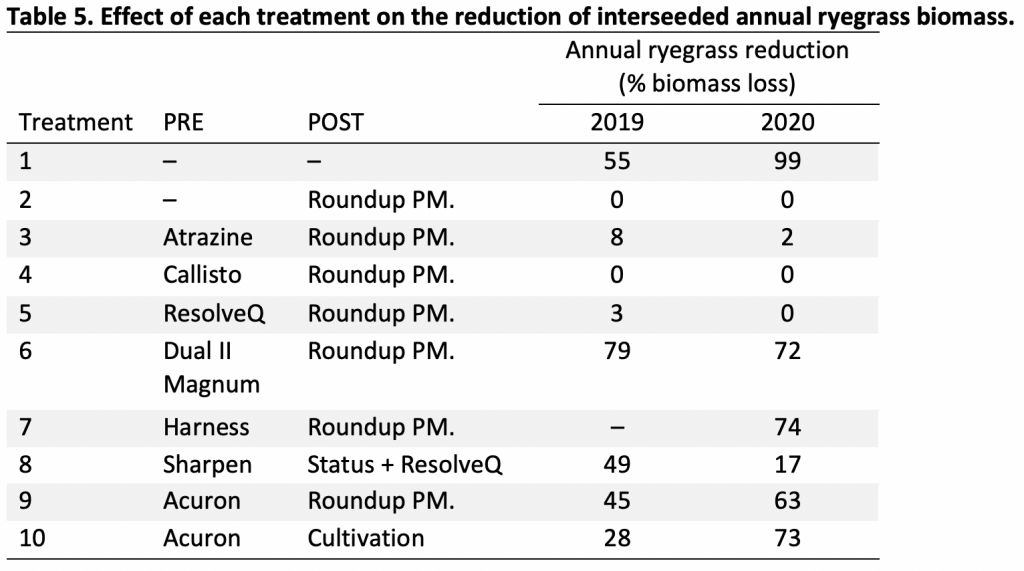

Objective 2.

On separate regions of the field near the plots described in Objective 1, we set up two trials investigating the use of cereal rye residue as a waterhemp suppressive mulch. While a cereal rye cover crop was not available for these trials, we transported rye residue from a nearby field and applied it immediately following planting. We used rates of 0, 3570, and 7140 lbs/A. The high- and mid-rates represent attainable rye biomass production in NY with- and without fertilizer, respectively (Mirsky et al 2013; Pethybridge et al 2019). Plots were 5’ by 10’ and each treatment was replicated four times per trial in a randomized compete block design. Waterhemp control was measured in the same manner as Objective 1.

Results and Discussion

Objective 1.

In 2020, waterhemp control was generally similar as 2019 (Table 2). Soil was dry at the time of pre-emergence application but we received 0.9” rain in the first 10 days after application, which was likely sufficient for activation. ValorSX did not perform as well as in the previous year, possibly related to weeds that had germinated prior to activation. WarrantUltra plus metribuzin remained very effective, providing further evidence that at least two effective modes of action – WSSA groups 14 and 15 in this treatment – are necessary for successful control.

In the post-emergence-only treatments, this year the Warrant improved the effectiveness of the Roundup and Xtendimax, probably due to our earlier planting and spray dates in 2020 that likely allowed more waterhemp to germinate after the post-emergence application, making use of the residual activity of the Warrant.

Similar to the previous year, the two-pass programs were generally more effective than the pre- or post-emergence-only programs. Having two passes reduces the burden on each pass. So if conditions are not optimal in one of the passes, the other pass can help ensure successful control is still achieved. They are also generally more expensive, but inclusion of more diverse chemistries and/or non-chemical tactics can reduce the risk of worsening the resistance problem.

In our partial budget analysis, the highest grossing (highest yielding) treatments were generally the most profitable (Table 2). The high yields of the row cultivation treatment may reflect the increase in soil aeration and nutrient release associated with soil disturbance. But also, due to small plot size there was some variability in yield results due to random chance.

Our waterhemp production and emergence model demonstrates that programs that control 100% of the waterhemp can result in greatly reduced emergence in subsequent years, whereas programs achieving 98% control or less will perpetuate the problem (Figure 1). Although 95% control would likely allow farmers to avoid a crop yield loss, the resulting waterhemp seed production and increase in emergence in subsequent years would likely make successful control more difficult over time.

Objective 2.

Across the two trials, cereal rye cover crop residue at high (7140 lbs/A) and medium rates (3570 lbs/A), representing biomass NY farmers could attain with- or without-fertilizer, provided an average of 87% and 73% waterhemp control compared to the untreated check, respectively. Used alone, these levels of control may be sufficient to avoid soybean yield loss. But this tactic could also be used in conjunction with a herbicide program. In such a system, 99% waterhemp control could be achieved with the high level of rye residue plus a herbicide program that only provides 92% control when used alone.

References

Davis AS, Fu X, Schutte BJ, Berhow MA, Dalling JW (2016) Interspecific variation in persistence of buried weed seeds follows trade-offs among physiological, chemical, and physical seed defenses. Ecology and Evolution. 6:6836–6845

Heneghan JM, Johnson WG (2017) The Growth and Development of Five Waterhemp (Amaranthus tuberculatus) Populations in a Common Garden. Weed Science. 65:247–255

Langemeier M (2018) Projected Corn and Soybean Breakeven Prices. Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Farmdoc Daily 8:66

Mirsky S, Ryan M, Teasdale J, Curran W, Reberg-Horton C, Spargo J, Wells S, Keene C, Moyer J (2013) Overcoming Weed Management Challenges in Cover Crop–Based Organic Rotational No-Till Soybean Production in the Eastern United States. Weed Technology, 27(1), 193-203. doi:10.1614/WT-D-12-00078.1

Pethybridge S, Brown B, Kikkert J, Ryan MR (2019) Rolled-crimped cereal rye mulch suppresses white mold in no-till soybean and dry bean. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems. doi:10.1017/S174217051900022X

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the New York Farm Viability Institute for supporting this project.

Disclaimer: Read pesticide labels prior to use. The information contained here is not a substitute for a pesticide label. Trade names used herein are for convenience only; no endorsement of products is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products implied. Laws and labels change. It is your responsibility to use pesticides legally. Always consult with your local Cooperative Extension office for legal and recommended practices and products. cce.cornell.edu/localoffices

For more information on this project, check out: https://nysipm.cornell.edu/agriculture/weed-ipm/