Social Networks and International Relations

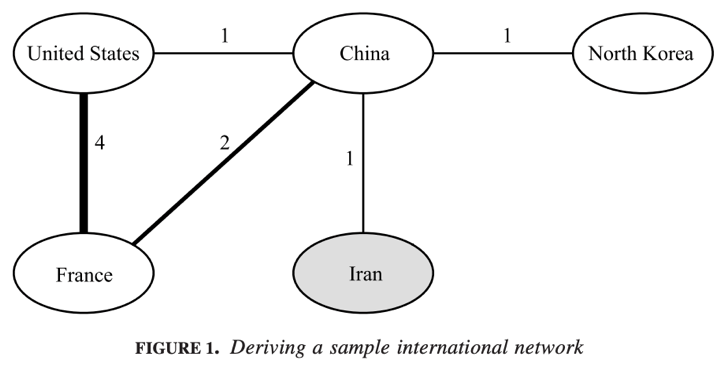

The social network theory describes the distribution of power amongst nodes. Betweenness measures the centrality of a node in a network, and how it spans structural holes most effectively. Dependence measures the number of social relations a node has while exclusion measures the power a node has as an access point for other nodes within the network. The research paper introduces degree centrality, which is “the sum of the value of the ties between that node and every other node in the network”, that is how much access a particular node has to other nodes. An example of an international network is shown below. France has the greatest degree centrality in this network while the United States (U.S.) and China tie for second. In terms of betweenness, dependence, and exclusion, China has the highest social power. This is because all nodes must pass through China to get to other parts of the network.

Social network theory provides intuition on the relative power each state has within a network but it also comes with a caveat: social relations may also impose constraints on autonomy and offer opportunities for influence. For example, China’s strong economic and political ties with Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam and Philippines, mean that it can exert external influence over their foreign policy. The South China Sea conflict is an example, where Vietnam and Philippines were limited in their diplomatic response when China seized their sovereign islands. Another point is that states within an alliance network tend to be involved in conflicts they rather avoid or are forced to enact policies that are against their own interest. A prominent example would be the network of alliances formed before 1945 that led to many European countries being dragged into World War II. A modern-day example would be the European Union, where its member states are forced to adopt economic policies, such as the Euro, and the open inter-state border policy (Schengen Agreement).

Another important measure of a node’s power is its bargaining power within the network. In international relations, smaller or more isolated countries have less bargaining power compared to larger states. Larger states tend to have more social relations and thus more “outside options”. In particular, this enables big powers such as U.S. and China tend to play the rules instead of playing by the rules. They do not submit to adjudication by international tribunals nor comply with their rulings. And as a result, many smaller states are forced to accept the imbalance in the social exchange. From the graph above, Iran and North Korea have very limited bargaining power because of their sole reliance on China in the network. On the other hand, nodes which try to exploit their bargaining power may also find “threats of exits” by their target nodes. Therefore, it is a continuous struggle for nodes to reduce the possibility of exit, thereby reducing their bargaining power, either by enhancing the benefits of the social exchange for the other node or via coercion.

This translates into the fundamental reality of international relations for small states. Small states have to work together to advance their common interests and amplify their influence in the geopolitical space. Otherwise, they risk having their sovereignty being encroached upon by larger, more dominant states. An example of this is the Forum of Small States, which was founded by Singapore in 1992, and has grown to 107 member states (over half the member countries in the United Nations). This portrays the incentive for smaller states to increase their betweenness in the social network and in turn, their bargaining power with larger states.

http://people.reed.edu/~ahm/Projects/SNAIR/NAIR.pd