Game Theory and Napoleonic Naval Warfare

Article: https://peterlevine.ws/?p=16536

Background resources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Trafalgar, https://www.britannica.com/topic/ship-of-the-line-warfare, and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sailing_ship_tactics provide a fair introduction to the material other than what’s from networks here.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the world’s great powers built warships with most of their cannons arrayed along their sides, allowing the ships to attack only to their sides with significant firepower (think Pirates of the Caribbean ships, but less weird). When ships fought in large fleets, the orthodox battle strategy capitalized on this geometry: each fleet would form a “line of battle” (below) a column sailing in a direction such that the ships’ broadsides faced the enemy, whereupon the two now-parallel fleets could blast one another with hundreds of cannon. Traditionally, the benefits of forming a line of battle are held to be that it allows better communication between ships in a fleet, minimizes the potential for friendly fire, and allows each ship to bring its entire broadside to bear on exactly one enemy.

Two fleets in lines of battle, this time at the Battle of the Chesapeake. Courtesy of https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Chesapeake#/media/File:BattleOfVirginiaCapes.jpg

Tufts University Professor Peter Levine’s musings on this topic in “Game Theory, Naval Warfare, and Derek Walcott” serve to highlight how this strategy in fact represented a Nash equilibria. Key to his analysis is that one of the key tactics of the era—called raking—was to exploit ships’ geometry by sailing across an enemy’s stem or stern, concentrating dozens of cannon on an opponent that could reply with only a few of their own (in his parlance, this is called crossing the T). For one fleet to attempt this against another without sailing towards the other fleet first and receiving consequent raking fire, Levine states it would have to first sail ahead of its enemy and then turn towards it—something difficult to do when ships’ speeds were roughly equal and maneuvering difficult. As neither fleet would gain from from turning towards the enemy and neither would get ahead, Levine concludes that this strategy—forming a line of battle and sailing parallel to the other fleet—was a best response to itself, and thus represented a Nash equilibrium.

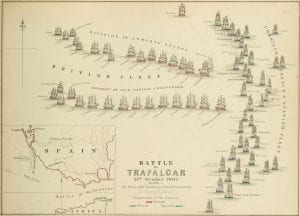

Levine goes on to mention battles in which English fleets deviated from the strategy above and sailed orthogonally towards a French and Franco-Spanish fleet. In the first battle Levine mentions, it was likely unplanned. In the second—the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar—it was by careful design: the English fleet divided itself into two columns, each of which sailed orthogonally to the Franco-Spanish line, taking raking fire for around 45 minutes before crashing through it and beginning a general melee. The English would go onto isolate the middle of the Franco-Spanish fleet to score a decisive victory. Levine considers both battles to be counterexamples to his thesis.

A depiction of Nelson’s strategy at the Battle of Trafalgar. Courtesy of https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Battle_of_Trafalgar,_Plate_1.jpg

However, at the Battle of Trafalgar, there exists a decent possibility that the English strategy was a best response to the likely Franco-Spanish strategy of forming an orthodox line of battle. The English admiral, Lord Nelson, desired to keep the Franco-Spanish fleet from escaping—which they could if both fleets formed parallel lines of battle—thus reducing the reward he would get for forming his own fleet into a line of battle. Moreover, he may have estimated that the poor gunnery of the French and Spanish ships would lessen the effect of the raking fire, thus reducing the negative reward he would get for directly charging the Franco-Spanish fleet. In his eyes, this may have made the unorthodox option a better response to the likely Franco-Spanish strategy than the orthodox line of battle.

(As for the French and Spanish, their admiral believed his fleet was too inexperienced to do more than form a line of battle, despite likely anticipating Nelson’s strategy.)

Consequently, it’s possible that Levine underestimates how applicable game theory is to naval battles of the era.