Bianca Moebius-Clune1, Maryn Carlson1, Daniel Moebius-Clune1, Harold van Es1, Jeff Melkonian1 and Keith Severson2, 1 Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, Cornell University and 2 Cornell Cooperative Extension Cayuga County

Farm Background

Donald and Sons Farm in Moravia, NY grows about 1,300 acres of corn and soybean annually. Robert and Rodney Donald have been practicing variable rate N application for a number of years, taking advantage of their RTK-GPS system for soil sampling, input applications and yield monitoring. Until 2011, the farm used N application rates recommended by A&L Great Lakes Laboratories, based on soil tests done by field management unit. The Donalds applied the bulk of their fertilizer N at sidedress time, as they knew that early season applications run the risk of losses during wet springs. Recommendations ranged across their farm from 195 to 260 lbs of total N per acre, of which the Donalds applied 22 at planting. In 2011, they spent $107,000 on N fertilizer – four times what they spent in 2000, due to increasing prices and a shift toward ever-higher recommended rates as yield potentials increased.

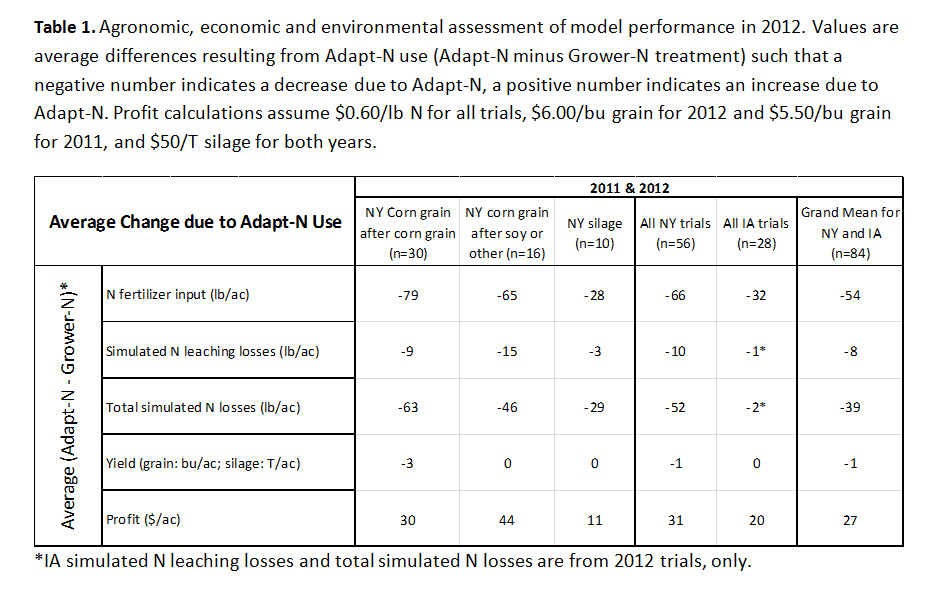

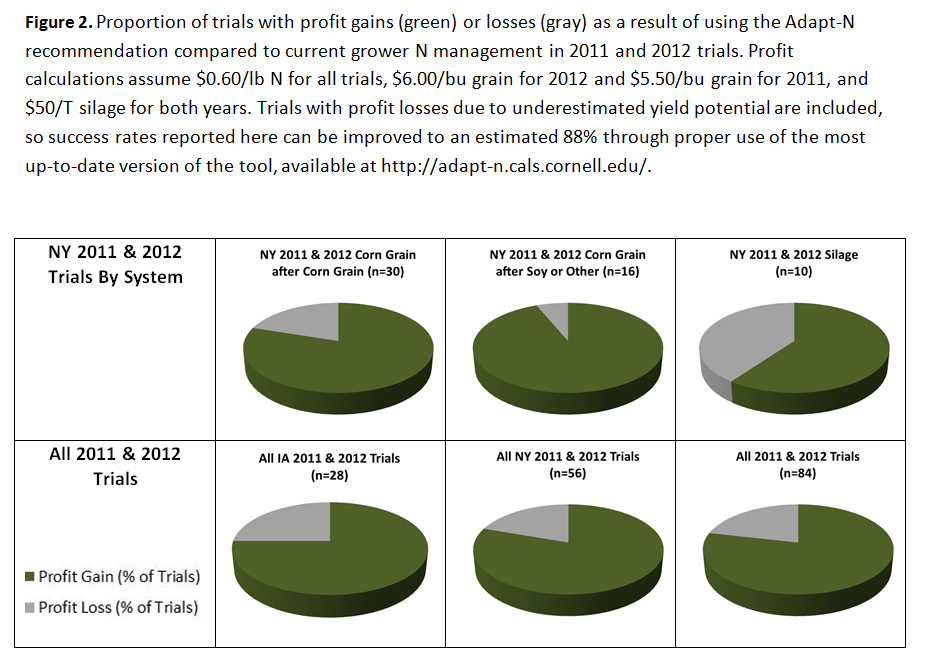

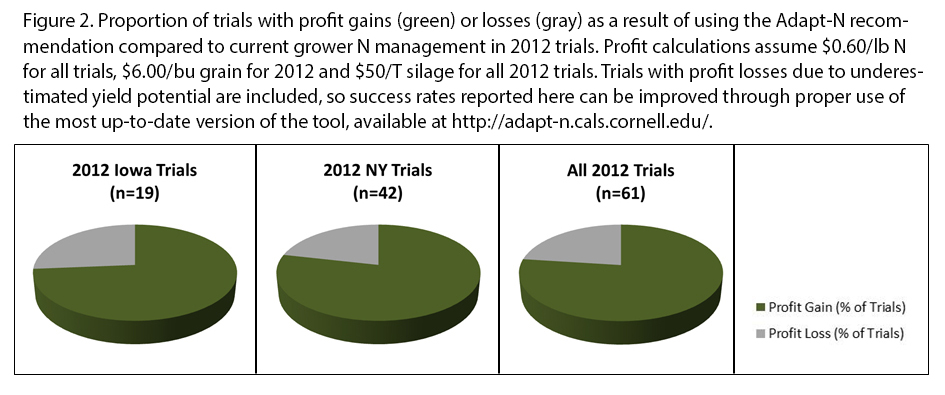

These large expenditures were a strong incentive to seek new tools to optimize application rates. As Rodney put it, “Money talks…and with what we are getting in corn for what we are putting on in ammonia, we’re not gaining.” In 2011, the Donalds decided to collaborate on the NY state-wide Adapt-N beta-testing effort. After the dry spring, the Adapt-N recommendation for their trial field was only 80 lbs N/acre, while their standard recommendation was 220 lbs N/acre. To their surprise, there was no yield penalty from reducing the N rate by 140 lbs N/acre. In state-wide trials, 2011 Adapt-N results were also very promising: 86% of trials showed higher profits using the Adapt-N rate, with an average increased profit of $35/acre (Moebius-Clune et al, 2012).

“I was pretty amazed with the program,” said Robert, who decided to participate in a workshop on Adapt-N at Cornell University in March 2012. He added, “Once you get the hang of the program it’s easy to use.”

The Adapt-N tool is transforming the way N recommendations are made by using high-resolution climate data and a dynamic simulation model to provide weather-adjusted, site-specific, in-season nitrogen recommendations. What sets Adapt-N apart from other methods for determining crop N needs is its explicit accounting for the interaction between early season weather and other factors like soil characteristics and management decisions. After a dry spring, N that has mineralized from organic sources or was applied early in the season remains available in the soil, so less needs to be sidedressed. But in a wet spring, N is easily lost from the system and thus more fertilizer N must be applied. That difference between years could be as much as 100 lb N/ac. Not only does such unmanaged uncertainty cut deeply into growers’ profits, but the environmental consequences are significant: leaching of excess nitrate affects water quality, and denitrification contributes to emissions of nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas, that also depletes the ozone layer. Realizing that recommendations from Adapt-N could lead to significant savings for the farm (estimated at $70,000 for 2011 after a very dry spring with low losses) the Donald Brothers decided they were on board.

Whole Farm Implementation of Adapt-N Rates

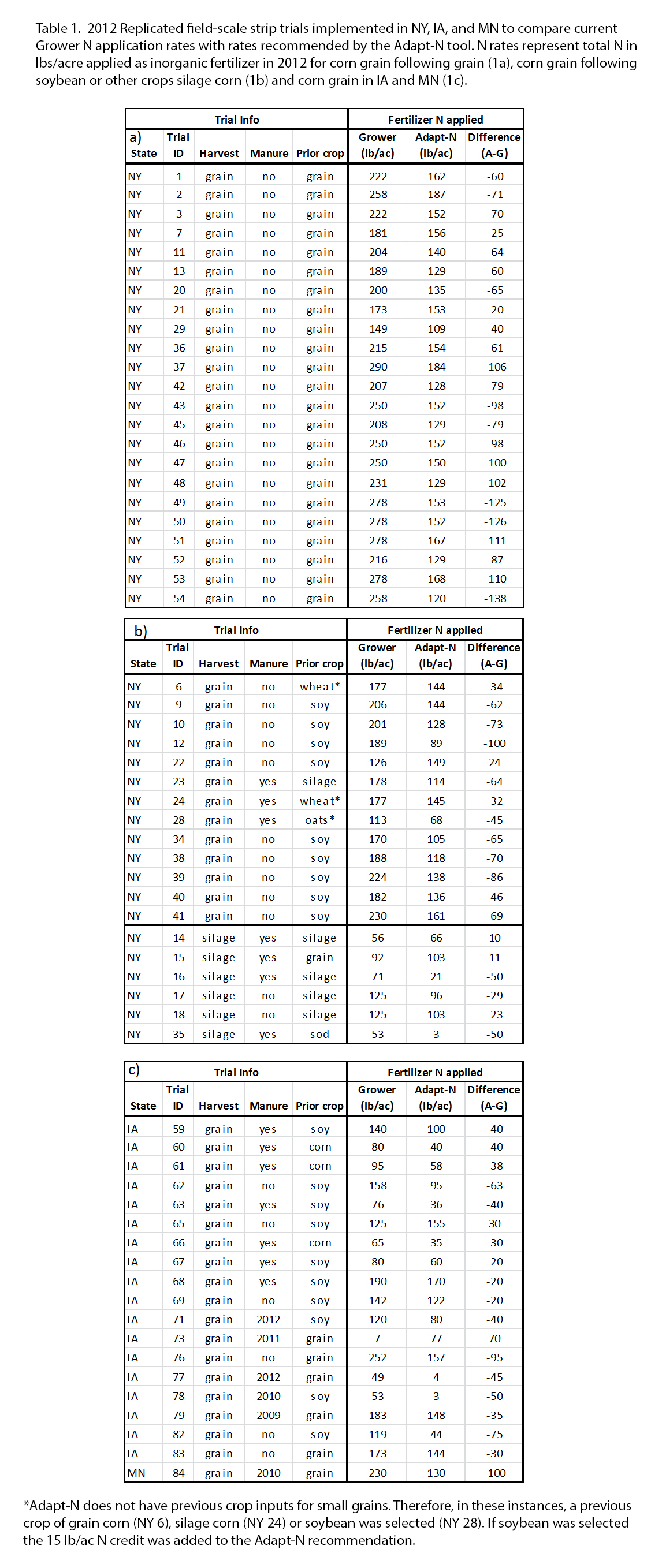

For the 2012 growing season, the Donalds used Adapt-N on their whole farm and implemented numerous trials. Robert entered the farm’s 90 management units into his account that spring via the user-friendly Adapt-N interface. “I spent one Saturday afternoon and all day on Sunday,” Robert noted. Between June 8 and 21, Rodney sidedressed 922 acres of corn, using their RTK-GPS system to target their variable rates. Recommendations from Adapt-N varied from 65 to 190 lbs N/acre among management units, depending on local temperature, precipitation, soil texture and organic matter content (varying from 1-6%), as well as the date of sidedressing. On each day of sidedressing, Robert entered updated N recommendations into their system (provided by the daily automatic Adapt-N sidedress alerts) for the fields to be sidedressed that day. He transferred this information to their calibrated RTK-GPS-guided anhydrous ammonia sidedresser via a USB device to automatically adjust N rates on-the-go.

Rodney sidedressed entire fields with the Adapt-N rate, except for single or replicated comparison strips of the conventional “old” rate implemented on 15 of their 18 corn fields. Most of the strip trials followed an AOOA design (with “A” representing the Adapt-N rate and “O” representing the old rate).

Agronomic, Economic and Environmental Results

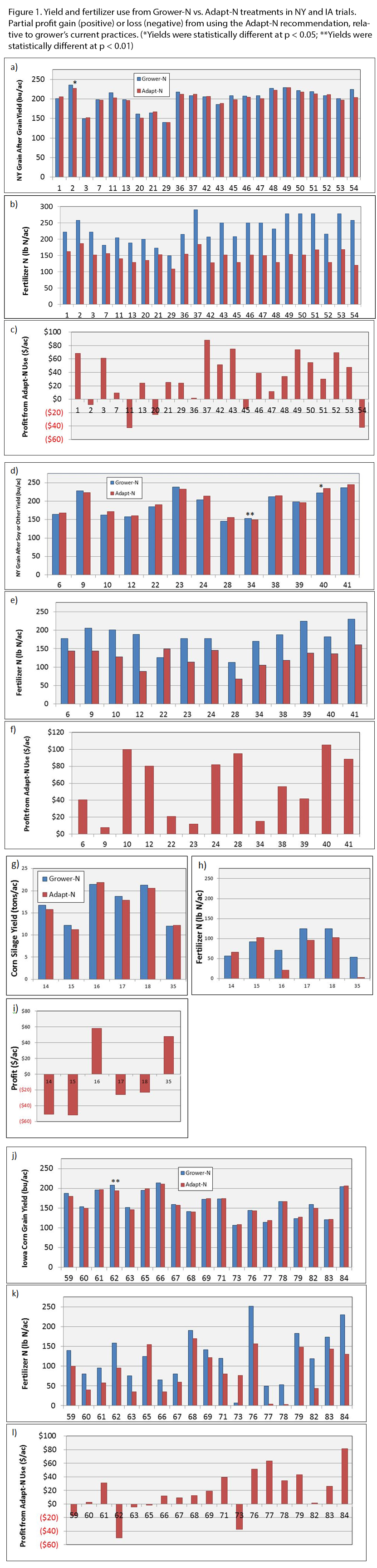

N rates as applied and yield monitor data for each trial area were retrieved from the Donalds’ AgLeader software at the end of the season. Yields and fertilizer application rates were visualized in map format and quantified within management units or as field-length strips.

Based on analysis of GIS data from the entire farm, Adapt-N resulted in profit gains in 83% of the trials. Averaged across all trials, savings were approximately $42/ac, with estimated total savings of over $30,000 for the farm after the fairly normal 2012 spring. Fields reached or exceeded the estimated yield potential in almost all cases, indicating that the Adapt-N recommended rates were high enough to achieve the expected yield. Yield losses were negligible (2 bu/ac) despite N fertilizer reductions by an average of 87 lbs/ac across all 24 fields. Yield maps visually emphasized the lack of yield response in the higher N rate strips for almost all trials, as well as the potential impact of field variability on harvest yield.

The only cases of profit loss occurred in four trials, all exceeding the expected yield by up to 35 bu/ac. Yield losses could have been minimized with more precise expected yield inputs; the Donalds had entered a flat yield potential of 200 bu/ac for all fields, rather than basing the input on past field-specific yield records. Adapt-N is a precise tool that already accounts for the risks of uncertainty and differential losses from over and under-fertilization. Therefore, a good estimate of expected yield is critical to attaining accurate N recommendations.

Savings from whole-farm implementation of Adapt-N were coupled with significant environmental benefits. Informed by Adapt-N, the Donalds applied a non-area-weighted average of 87 lbs/ac less than recommended by A&L Laboratories across the implemented trials. The decrease in N applications reduced simulated total environmental N losses (until 12/15/2012) by an average of 70 lbs/ac, and reduced N leaching losses by an average of 10 lbs/ac. In total, they saved about 67,000 lbs of unneeded N in 2012.

Refining Adapt-N Use in 2013

When asked whether they were planning to use Adapt-N again next year, Robert answered with an unequivocal “Oh yeah!” and added, “Gotta refine our use of the tool some.” Robert recognizes that for a precision tool like Adapt-N, a reasonable expected yield is particularly important. One of the biggest things Robert plans to change: He will use variable estimated yields for each management unit in 2013, based on 3 to 5 years of yield records for each management unit. He noted that one of his fields in Scipio, NY “won’t do 175 in the best of years. That’s where N is wasted,” while, “other fields can regularly reach 250 bu/ac” if given enough nitrogen. Also, he plans to use the new soil series name inputs that became available last June to further improve the precision of the recommendations.

The trials implemented at Donald & Sons Farm have greatly helped the team assess Adapt-N’s performance and demonstrate the efficacy of using the tool in conjunction with GPS equipment. Growers with similar technological capabilities can likewise maximize the potential of Adapt-N to improve their profits and reduce N inputs and losses.

More information. Adapt-N supporting publications, an in-depth training webinar, and access to the web-interface are available at http://adapt-n.cals.cornell.edu. This case study has been supported by funds from New York Farm Viability Institute, the USDA-NRCS Conservation Innovation Program, and the International Plant Nutrition Institute.