Brexit: Just Another Application of Game Theory

One of the largest issues occurring today in the world is Brexit. A portmanteau of the words ‘Britain’ and ‘exit’, Brexit refers to the act of the United Kingdom (UK) leaving the European Union (EU). It followed the referendum held in the summer of 2016 when the UK government allowed the general electorate to vote on whether or not the UK should leave. The option to leave won in the referendum by the slimmest of margins (51.9% to 48.1%). Since the government promised that it would implement the results of the referendum, it initiated its withdrawal from the European Union.

However, one problem that both parties, the UK and the EU, are facing is agreeing up on an exit deal that suits all parties involved. Theresa May, the current Prime Minister of the UK, promised that the official date of exit would be March 29th, 2019. It’s imperative that both institutions reach a deal as to not message up fiscal policies and trade between the two entities, or worse, the global economy. At the same time, though, citizens and Members of Parliament are divided on whether or not this is a good deal in the first place. Thus, colloquially, people who want the UK to remain in the EU are referred to as “Remainers”, whereas people who support the UK leaving the EU are known as “Brexiteers”.

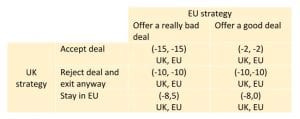

Upon further analysis of this crucial deal making process, we find that we can break it down simply into the Prisoner’s Dilemma model we learned about in class. Let’s assume a case where there are only two choices for both the UK and the EU. The EU offers either a good or bad deal, and the UK makes a decision based off of this deal. Note that this may not be like the real time quick decisions we learned about through the prisoners dilemma in class, but it still follows the same general principle. Since there is a deal being made, both parties have the opportunity to either cooperate with each other to reach what would be considered a “fair deal”, or one party could try and make a deal to benefit itself. In any case, since the UK is leaving the EU, the EU has to come up with an exit strategy, or deal. Then, it is up to Prime Minister May to convince her MPs, and ultimately the public, that it is a fair deal.

Neil McCulloch of the Politics created the simulation above. You may notice that even in the best case scenario, there may be a negative payoff for the UK even if both cooperate. His reasoning was that if the UK gets a good deal and decides to leave, based on the global sentiment and simple fact that the UK doesn’t have as much pull in the global markets as the EU does, the UK is unlikely to get the same access to other countries and deals that it would when it was a part of the EU. Thus, it’s a still net negative payoff. Overall though, it’s obvious that the best strategy for the UK would be to accept any deal that the EU presents, as it seems that the payoffs based on this simulation would be better for the UK in either scenario. These numbers make sense, as exiting the EU without any deal would create mass trade confusions and economic instability which hurts all parties involved. Taking any deal given would ensure that this chaos does not ensue, though it may not be what the UK wants. As for the EU, its payoff depends solely on the type of deal it presents and how it’s structured, thus making the payoffs for it hard to gauge.

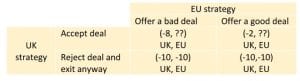

Based on these justifications, it seems as if the UK is in a terrible situation either way. However, some analysts argue that this may not be the case. They are proposing that the UK could simply just stay in the EU. Lawyers are currently seeing whether or not a country can go back on its decision to exit the EU. If this holds true, then the way this shapes out could be different (see below).

Now, the UK has another strategy to work with, which alters the dynamic of the game itself. We see that if the EU offers a deal and the UK decides to stay, it looks bad on behalf of the UK. It signals to the world that it is unconfident in its abilities to perform as an individual economic government. On the contrary, though, Remainers would argue that there is actually no harm done, and thus its payoff should be 0. Thus, the numbers above may be subject to the reader’s interpretation.

Nevertheless, though, we see that there is a clear strategy for the EU. Should the EU offer a bad deal, it would force the UK’s hand in choosing to stay. This would be a huge advantage for the EU, as it would essentially signal to the world that it holds such power over one of the most relevant countries in the world, the UK.

This begs the question, what should the UK do. Although there is no clear answer to this question, yet, it’s interesting to see that maybe the UK shouldn’t even consider staying. If it chooses to stay, it gives the EU a clear path of action. However, if it takes out this action and sticks to either accepting or rejecting the deal, then it’s game on for the EU.

Resources: http://www.politics.co.uk/comment-analysis/2017/03/15/the-game-theory-of-brexit, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-32810887,