Quiz can be taken here on Buzzfeed or in the frame below.

QUIZ RESULTS

I – You are Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City!

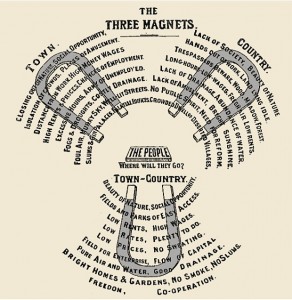

Figure 1: “Ebenezer Howard’s Three Magnets.” The Guardian, December 5, 2014, sec. Cities. Image in public domain.

Congratulations; you are a network of self-sufficient, human-scaled communities embedded in the natural environment, which Ebenezer Howard theorised in his book, Garden Cities of To-morrow (Fishman, 1998, p. 127). Howard presented this idea with many iconic diagrams, including the Three Magnets Diagram (Figure 1) which shows three magnets facing the centre of the image. Two of the magnets represent the Town and the Country, each with two poles denoting the negative and positive aspects of the city and the countryside. The third, however, seems to have two positive poles, and represents Howard’s synthesis of the two: the Town-Country. In the centre are The People and the question Howard poses to the reader, ‘Where will they go? (Ross, Mogilevich, & Campkin, 2014). As the diagram suggests, Howard’s vision of the network of garden cities is—like many other utopian visions of human habitat—shaped by the desire to address the troubles of the industrial city. More nuanced than the rhetoric of the ‘Back to the Land’ agrarians, however, Howard’s diagrams listed both the perceived advantages and disadvantages of the city, and sought to synthesise the former with the benefits of country living. The result would be a ‘group of slumless, smokeless cities’ (Richert & Lapping, 1998, p. 126).

Figure 2: Ebenezer Howard, A Group of Slumless Smokeless Cities, 1902, http://www.spur.org/sites/default/files/migrated/images/F4.jpg. Image in public domain.

Other images from Howard’s seminal book include a series of diagrams that show how a hypothetical Garden City would be structured and where it would be located in relation to a larger metropolis (example in Figure 2). Garden Cities would be composed of concentric circles of urbanism, railroads, canals and greenery. A Garden City would be compact and beautiful. Its expansion would necessarily be limited by a ‘greenbelt’ around it and its population would be set at around 30,000 inhabitants (Fishman, 1982, p. 30). Health would be of utmost importance; factories would be located at the periphery of each garden city, connected to the circular railroad and separated (albeit still within walking distance) from residential areas (Fishman, 1982, p. 40). The town’s centre would not be a place of work but a place of leisure and civic enterprise.

Ultimately the Garden City model could not sufficiently attract the populations necessary for Howard’s vision to be realised. Those Garden Cities realised have devolved into bedroom suburbs and the movement had no mechanism through which it can replace the industrial city. Still, the Garden City movement left a great legacy. David Pinder writes that the movement’s schemes have taken root in many mainstream debates about urban development, though with a lack of consideration for its historical contexts or Howard’s commitment to large-scale social change through planning (Pinder, 2002, p. 233). Although Howard certainly didn’t invent the concept of forestry or agricultural areas surrounding and limiting the extent of urbanism, the modern greenbelt—especially in the context of the 1930’s ‘Greenbelt Cities’ of the United States Resettlement Administration—owes its form to the Garden City (Fishman, 1982, p. 38). Robert Fishman stresses the importance of Ebenezer Howard’s vision, further crediting him with shaping the principles of such contemporary movements in urban planning as the New Urbanism and Smart Growth; ‘[Howard’s] Garden City embodied all the ideals now championed by the New Urbanists. His utopias are “pedestrian pockets” and “transit-oriented development”’(Fishman, 1998, p. 128).

II. You are the City Beautiful!

You’re not just a beautiful city… you’re the City Beautiful, a movement and philosophy of urban planning and architecture most recognised through Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and the 1909 Plan of Chicago. The movement emphasised the beautification of cities and creating a sense of monumental grandeur. Daniel Burnham, an American architect, is largely associated with both the plan and the exhibition, and with the movement at large. The World’s Columbian Exhibition was designed by Burnham and Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. and featured parks, fountains, statues and the Midway Plaisance, a forerunner of the modern amusement park (Daniels, 2009, p. 181). The movement adopted these and a type of neo-classical, monumental architecture that was meant to inspire civic unity, virtues and adoration in all the urban inhabitants (Wilson, 1994, p. 69). The Chicago Plan, with its massive public park system and wide boulevards, would later typify the larger model of the City Beautiful. It would contain a civic centre and height limits would ensure other buildings prostrate themselves to this civic centre, the symbol of the metropolis’s unity and its inhabitants’ civic duties. The City Beautiful would contain tree-lined boulevards, formal gardens and public spaces with fountains (Daniels, 2009, p. 118). This project of beautification can be juxtaposed with the harsh realities of the industrial city, out of which many utopian visions of the city spring.

Figure 3: The Statue of the Republic and Administration Building of Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

Image in public domain.

In many ways the City Beautiful is conceived of as a civilisationist project based solely on aesthetics. It is for this that many voiced criticism to the movement and its ideals. Social worker and city planning advocate Benjamin Marsh is noted to have brushed off the City Beautiful as ‘too concerned with cosmetic display’ repudiated its claim to be able to uplift, civilise and enlighten citizens with scenes of public beauty and a sense of greater purpose. He writes that while ‘parks, civic centres and other great public works are attractive’, the poor could barely afford to ‘escape from their squalid … surroundings to view the [City Beautiful’s] architectural perfection and to experience [its] aesthetic delights’ (Wilson, 1994, p. 75).

It is perhaps for these reasons that Jane Jacobs labelled the movement an ‘architectural design cult’ (Rybczynski, 2014, p. 140) but the movement’s criticism came from architects too, and much earlier. Architect Cass Gilbert declared, ‘let us have the city useful, the city practice, the city liveable, the city sensible, the city anything but the city beautiful’ (Wilson, 1994, p. 75). Regardless of which these Cities is the most desirable, Gilbert and Jacobs’s notions of architects obsessing over the design of the City Beautiful are not amenable to a precise contrast with ideas of social reformers worrying about the real issues. It is precisely for the purpose of social reform that proponents of the City Beautiful advocated the use of aesthetics. Their legacy remains important in establishing the importance of public park systems and to the grand design of public space and civic centres in cities in the United States and abroad, most notably the Australian cities of Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne, where the City Beautiful – despite its American beginnings – seems to have taken a life of its own (Freestone, 2007, pp. 30–32).

III. You are Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse!

You’re rational, efficient and oh so modern! You’re Le Corbusier’s Radiant City! Swiss Architect Le Corbusier explicitly wrote that ‘plans are not political’. For him the problems of the city were technical ones and the intervention needed was the design of a city that was supposedly objective, rational and conscious in its encompassing all aspects of life (Fishman, 1982, p. 47). The people behind these plans were naturally technocrats, experts detached from political life and the pressures of constituents (Fishman, 1982, p. 48). He espoused rational architecture and city planning as the ‘exact prescription for [the city’s] ills’ and theorised that only when contemporary society is aware of this prescription can ‘the great machine … be put in motion and begin its functions’ (Fitting, 2002, p. 69). The result is a Radiant City, one worthy of human effort and time (Fishman, 1982, p. 31). The Radiant City teems with considerable vertical density, where the skyscraper functions as the major thoroughfare, ‘a street in the air’ in Le Corbusier’s words. This would maintain density while eliminating the ‘decaying, soulless’ streets of the old city (Fishman, 1982, p. 33). This is also where much of human social interaction outside work and entertainment would occur, as each of the residential skyscrapers was self-sufficient, containing schools, cleaning services, food stores, tennis courts, swimming pools and even beaches. Only 15 per cent of the skyscraper’s parcel would be built, however. The rest would be set for parks and playing fields. The city’s is rationally divided and rationed for different uses (Fishman, 1982, p. 50).

Figure 4: Le Corbusier’s Radiant City. Photograph of model taken in 1930. Image used under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, courtesy of Foundation Le Corbusier, Paris.

Criticisms of the Ville Radieuse often focus on its being designed for a scale that is far too large, almost certainly alienating for human use. Additional criticism rests on the fact that such city plans as Le Corbusier’s came ‘from above’ as opposed to formulated by the citizens, or that they were designed for implementation ‘from above’, with no regards to conditions of the city on the ground (Fitting, 2002, pp. 69–70). Despite criticism, however, Le Corbusier’s legacy is clear in the emergence of modern architecture and the international style in the first half of the twentieth century. It is also evident in Chandigarh, the planned Punjab capital city for which he was master-planner, and in Brasilia, the planned Brazilian capital that was very much built after his ideals (Fitting, 2002, p. 70). Le Corbusier’s imprint can also be felt in modernist plazas exhibiting his signature ‘towers in the park’ aesthetic, such as the Empire State Plaza in Albany, New York, and more generally perhaps in the model of the ‘professional planner’ that prevailed long after his death. It is perhaps telling that these three prominent examples are state or national capitals, further evidence of the appeal of Le Corbusier’s rational plans to figures of authority or further fuel to the association between his ideals and a modernist strain of authoritarianism.

Conclusion

Despite their diversity and the striking range of their oft-unrealised ‘finished products’, there certainly exists a similarity between these many utopian visions of the city: they are based primarily on the imposition of spatial form (Pinder, 2002, p. 233). This planned and organised form is the setting required for the unfolding of the different congenial societies of the planners’ dreams; where the city is made efficient, rational and legible, where the ills of the industrial city disappear, or where a sense of citizenship and civic duty is inspired. The promise is that through meticulously sorting out the spatial and built form first—so as to include detailed illustrations of how factories, offices, schools, modes of transport, and even living rooms, would like (Fishman, 1982, p. 27)—the social issues whose resolution is at the centre of these plans would be resolved. It was not until the latter half of the nineteenth century when criticism was voiced at the seemingly surgical, design-based solutions proposed to resolve the socioeconomic ills of the city.

Jane Jacobs, author of the Death and Life of Great American Cities, would famously amalgamate the three visions of the city into the ‘Radiant Garden City Beautiful’ (Ward, 2011). This phrase both presents these three visions as the governing paradigms in planning of the time, thereby highlighting their legacy and significance, and indicates that Jacobs used the phrase as short-hand for everything she criticised: visions she believed were irreconcilable with the need to preserve and build upon already existing communities in cities.

References

- Daniels, T. L. (2009). A Trail Across Time: American Environmental Planning From City Beautiful to Sustainability. Journal of the American Planning Association, 75(2), 178–192.

- Fishman, R. (1982). Urban Utopias in the Twentieth Century: Ebenezer Howard, Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press.

- Fishman, R. (1998). Howard and the Garden. Journal of the American Planning Association, 64(2), 127–128.

- Fitting, P. (2002). Urban Planning/Utopian Dreaming: Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh Today. Utopian Studies, 13(1), 69–93.

- Freestone, R. (2007). The Internationalization of the City Beautiful. International Planning Studies, 12(1), 21–34.

- Pinder, D. (2002). In Defence of Utopian Urbanism: Imagining Cities after the “End of Utopia.” Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography, 84(3/4), 229–241.

- Richert, E. D., & Lapping, M. B. (1998). Ebenezer Howard and the Garden City. American Planning Association. Journal of the American Planning Association, 64(2), 125–127.

- Ross, R., Mogilevich, M., & Campkin, B. (2014, December 5). Ebenezer Howard’s three magnets. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/dec/05/ebenezer-howards-three-magnets

- Rybczynski, W. (2014). City Life. Simon and Schuster.

- Ward, S. (2011, October 22). Jane Jacobs. The Independent. Retrieved from http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/jane-jacobs-480896.html

- Wilson, W. H. (1994). The City Beautiful Movement. Johns Hopkins University Press.