By Paige Roosa

I. A brief history of urban agriculture

Urban agriculture has been an important element of the city landscape since the origins of urbanization, yet it is a land use frequently ignored in policy legislation or planning schemes. Ebenezer Howard’s planned ‘Garden City’ dedicated five-sixths of allotted city land to food production (Oswald, 2009). The practice of cultivating “Victory Gardens” during World War II accounted for 40% of produce consumption in the United States (National World War II Museum). As Janet Oswald notes, however, once peace and prosperity had been restored in the country, the land used for these Victory Gardens was replaced with more lucrative uses (Oswald, 2009). As the global industrial food system flourished in the United States over the last few decades, the need for home food production has declined. Despite a food system concentrated on overproduction, the USDA recently reported that 14.5% of American households were food insecure in 2012 (Coleman-Jensen, Nord, & Singh, 2013). Food deserts can be a major contributing factor to food insecurity, and according to a 2012 documentary, A Place at the Table, roughly 75% of food deserts are urban (Jacobson & Silverbush, 2013). The mounting problem of food insecurity in urban areas has caused planning professionals to recognize the importance of planning in addressing an inadequate food system, and fostering a return of agriculture to the urban landscape.

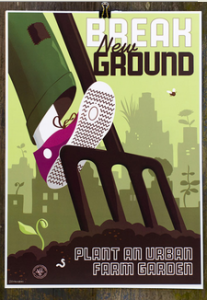

The incorporation of urban agriculture can take many forms – from backyard, raised-bed gardens, to community gardens and rooftop farms. In fact, the Portland, OR-based artist and activist Joe Wirtheim has recently been fighting for the “Victory Garden of Tomorrow” movement, which includes messages urging people to “eat real food,” “cultivate imagination,” and “break new ground” (Wirtheim, 2013). The New York Times recently featured Karen Washington, a resident of the South Bronx who started growing food for her family in 1985 and has recently begun growing food to feed the community, in a slideshow titled, “City Sprouting.” Washington’s farm is located across the street from her home and named “The Garden of Happiness.” The full slideshow can be viewed here.

II. Criticisms of urban agriculture

The notion that city dwellers could in fact feed themselves through backyard gardening is not without its critics. Harvard professor Edward Glaeser’s 2011 article titled, “The Locavore’s Dilemma: Urban farms do more harm than good to the environment” created quite a stir among proponents of urban agriculture. Skeptics of urban agriculture make the following arguments:

A community gardener at Hart to Hart garden in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, shows off some scallions (personal photo)

Urban farms can’t feed the city. Harvard Professor of Economics Edward Glaeser wrote, “while neighborhoods benefit from the occasional communal garden, it is a mistake to think that metropolitan areas could or should try to significantly satisfy their own food needs” (Glaeser, 2011). According to Karen Washington, owner of “The Garden of Happiness,” the community garden movement was never about urban agriculture, but about reclaiming abused land (Crouch, 2012). The goal of urban farms is not necessarily that of feeding entire city populations – some are used for teaching and empowerment purposes, others, such as the Eagle Street Rooftop Farm in Brooklyn, serve restaurants in the area.

Economic development should take precedence. In a recent blog post about Detroit featured on Time Magazine’s website, Jesse Jackson is quoted stating, “Detroit needs industry, housing and construction – not bean patches… if people want to farm, they’ll farm in zones” (Dawsey, 2010). Yet urban agriculture can be a source of job training, provide access to healthy food and reduce crime rates (Crouch, 2012).

Community gardens contribute to gentrification. Patrick Crouch managed a 2.5 acre urban farm in Detroit. He has discussed the possibility of community gardens leading to gentrification with residents of Detroit. According to Crouch and the people of color with which he has worked in the city, urban agriculture tends to attract young white people, which can be an indication of future gentrification (Crouch, 2012). Karen Washington, owner of The Garden of Happiness in the South Bronx, explained:

“the community garden movement was a means to take pride I and feel a sense of ownership in low-income neighborhoods. While growing food was important, it was secondary to the desire to push drug dealers out, stop illegal dumping, and create a little beauty in areas that were battling blight and absentee landlords… you have this new yuppie group coming in [to gentrified areas of Brookyln such as Park Slope and Bushwick] that is gung ho about urban agriculture…but the movement wasn’t about urban agriculture, it was about survival, taking back our communities” (Crouch, 2012).

The urban farm I worked on in Boston was just this – sure, it produced a great deal of food for the community, but it was initially created to take back a park that had become a site for drug-trafficking and crime. While the farm did bring in groups of white people that otherwise might not have visited Roxbury, residents of the neighborhood were happy to see this transition of the land.

Urban agriculture is toxic, because of lead contamination of the soil. Lead is prevalent in urban environments, as a result of years of use of leaded gasoline and lead paint. A study of urban gardens in 2008 researched the possibility for raised bed gardens (basically boxes filled with clean soil and compost) to decrease exposure to lead. The study gathered data from backyard gardens and urban farms in Roxbury, Massachusetts and concluded that these beds require maintenance and soil replacement every year because the rate of deposition of heavy metals in the air will effectively contaminate the top 3-5 cm of clean soil (Clark, Hausladen, & Brabander, 2008).

Two summers ago, I worked on the Cornell Cooperative Extension research project, “Healthy Soils, Healthy Communities,” gathering soil and vegetable samples to determine if produce grown in contaminated soil contained these toxic compounds. While the conclusions are not yet final, the data suggests that ingestion of lead compounds is more the result of direct soil ingestion as a result of improper washing of the produce. If produce is thoroughly washed before consumption, the chance of ingesting lead is greatly reduced. Furthermore, soil lead content at a concentration below 400 parts per million is considered safe by the EPA (Clark, Hausladen, & Brabander, 2008).

III. Conclusion: Urban Agriculture Can Help Increase Food Access to Nutritious Foods

Despite the various criticisms against urban agriculture, the positive implications of urban agriculture deem it a worthwhile practice that not only can provide communities with fresh produce at a reduced cost, but foster collective action within the community and offer ecosystem services such as reducing surface runoff of rainwater and reducing waste through the creation of compost from organic waste. In my own experience, I have found community gardens to be invaluable sources of escape from concrete sidewalks on hot summer days and offering city dwellers the opportunity to take a hands-on approach to learning about agriculture. There was one day when I was collecting samples in a Brooklyn community garden when I was approached by a seven-year-old who offered me a strawberry she had very proudly grown in her family’s plot of the garden. The young girl and her father were demure but clearly appreciative of the raised bed they’d been allocated.

Bibliography

Clark, H. F., Hausladen, D. M., & Brabander, D. J. (2008). Urban gardens: lead exposure, recontamination mechanisms, and implications for remediation design. Environmental Research , 107 (2008), 312-319.

Coleman-Jensen, A., Nord, M., & Singh, A. (2013, October 31). Household Food Security in the United States. Retrieved November 21, 2013, from Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service: http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/err-economic-research-report/err155.aspx#.Uo4pDmTF2kk

Crouch, P. (2012, October 3). Evolution or gentrification: Do urban farms lead to higher rents? Retrieved November 2013, 2013, from grist.org: http://grist.org/food/evolution-or-gentrification-do-urban-farms-lead-to-higher-rents/

Dawsey, D. (2010, September 9). So What’s Wrong with Urban Farming? Retrieved November 21, 2013, from Time Magazine: Blogs: http://detroit.blogs.time.com/2010/09/09/so-whats-wrong-with-urban-farming-anyway/

Glaeser, E. L. (2011, June 16). The Locavore’s Dilemma. Retrieved November 21, 2013, from Boston.com Op-Ed : http://www.boston.com/bostonglobe/editorial_opinion/oped/articles/2011/06/16/the_locavores_dilemma/

Jacobson, K., & Silverbush, L. (Directors). (2013). A Place at the Table [Motion Picture]. United States of America.

National World War II Museum. (n.d.). Victory Gardens at a Glance. Retrieved November 21, 2013, from The National World War II Mueseum: http://www.nationalww2museum.org/learn/education/for-students/ww2-history/at-a-glance/victory-gardens.html

Oswald, J. (2009, Summer). Planning for Urban Agriculture. Plan , pp. 35-38.

Wirtheim, J. (2013). Victory Garden of Tomorrow. Retrieved November 18, 2013, from Victory Garden of Tomorrow: victorygardenoftomorrow.com