By Eileen Cuevas

Chandigarh’s history as a city had always set it apart from other cities in the country thanks to its status as the country’s first planned city. Because it was planned, it was susceptible to the differing influential ideas of various planners at the time. In the end, it was urbanism that won out and developed Chandigarh into the city it is today. However, what were the effects of having a city modeled after urbanist ideas? In order to get a clear answer, one must look at the history of the city in question.

Around the year 1947, India had finally gained their independence from the British Empire. Shortly after gaining their independence, however, one of their wealthiest provinces, named Punjab, was split into two (Kemme 1992, 11). This separation resulted in India’s loss of Lahore—its rich, historic capital. In order to honor their efforts, the government of India decided to create a new city that would effectively be a “symbol of the potential of an independent India,” as well as provide its citizens with the “sense of unity and demonstrate its independence to the world” (Kemme 1992, 11). Additionally, none of the existing towns at the moment could house the new capital, for “none of them seemed capable of supporting the expansion necessary to provide for government functions,” especially as the population of the state began to increase with the migration of displaced people from Pakistan (Fitting 71-72). While the prime minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, was ecstatic with this plan, the project itself did not have much local political support due to its need of displacing 9000 inhabitants of the proposed site.

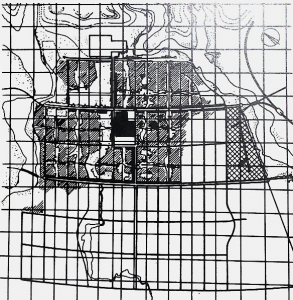

In order to plan out the new city, Nehru decided that it would be in the country’s best interest to hire architects who hail from countries abroad with some familiarity with the Indian way of life. This, in turn, led Nehru to contract American architect Albert Mayer as the planner for the new city. While Mayer wished to have his team help in creating the new city, there was little interest among them. Joining Mayer to aid in the project was Matthew Nowicki, a Siberian architect who was highly recommended by members of Mayer’s team. Together, they proposed a master plan that is “a culmination of the ideas which originated with Radburn and the Greenbelt Towns of the 1930s, as well as with the super block development of Baldwin Hills, an expression of the ideas of the English Garden City movement,” (Kemme 1992, 12). Unfortunately, due to an unforeseen plane crash that resulted in the death of Nowicki, the relationship between Mayer and the Indian government slowly disintegrated and the master plan was eventually abandoned. With no one to help plan the city, the Prime Minister turns to other architects, particularly those with less experience in the Indian way of life. This paves the way for Le Corbusier to take over the project, and, with nearly complete freedom, allows Le Corbusier to create a city in his vision from the ground up.

Le Corbusier’s main job involved planning the city itself, as well as the High Court, Secretariat, Assembly, Raj Bhawan and other major buildings, (Prakash 1983, 1). Within these plans was the motion to set aside an area to be designated as the Industrial Area. This Industrial Area, while not as traditional as most industrial areas, allows the city to have some sort of “Service Industry” which keeps “the city going,” (Prakash 1983, 8). At the same time, both planners and government did not want the city to become plagued with pollution issues, which led them to ban industries that produced smoke or “any other obnoxious effluents,” (Prakash 1983, 8). At the same time, many of the ideas included in the new master plan by Le Corbusier involved the ideas of Mayer and Nowicki, even though evidence suggests that Le Corbusier’s plan was not a “slightly modified version” of Mayer’s plan (Moulis 2012, 881). Yet, many things that were in Mayer and Nowicki’s original master plan for the city were excluded, such as a bazaar that contained room for “artisans and small businesses,” which would later on affect the economic base of Chandigarh (Kemme 1992, 12). Construction of the city lasted several years, but by the end of 1952, most government departments had moved from its temporary housing—the city of Simla—to Chandigarh (Fitting 2002, 72). By September 1953, the move was complete (Fitting 2002, 72). Thanks to Le Corbusier’s efforts, Chandigarh became to be considered to be one of the boldest experiments in planning as Chandigarh breaks the mold of traditional cities.

Today, Chandigarh is home to over 7 million people—6 million people above its intended occupancy. Many come to Chandigarh in order to appreciate its history, as well as get the experience of walking through an entirely planned city. Additionally, many satellite cities have grown around the city of Chandigarh in order to accommodate its population of over 7 million.

Part II: Urbanist Ideals: How Modernism has Impacted Chandigarh

References

Takhar, Jaspreet, and Vandana Babbar. Celebrating Chandigarh. Chandigarh: Chandigarh Perspectives in association with Mapin Pub, 2002.

Cooper, Frederick. Colonialism in Question: Theory, Knowledge, History. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

Fitting, Peter. 2002. “Urban Planning/Utopian dreaming: Le Corbusier’s chandigarh today.” Utopian Studies 13, no. 1: 69-93.

Kalia, Ravi. Chandigarh: In Search of an Identity. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1987.

Kemme, Guus. Chandigarh: Forty Years After Le Corbusier. Amsterdam: Architectura & Natura, 1992.

Moulis, Antony. 2012. “An Exemplar for Modernism: Le Corbusier’s Adelaide Drawing, Urbanism and the Chandigarh Plan”. The Journal of Architecture. 17, no. 6: 871-887.

Prakash, Aditya. Reflections on Chandigarh. New Delhi: B.N. Prakash, 1983.

Sarin, Madhu. Urban Planning in the Third World: The Chandigarh Experience. London: Mansell Pub, 1982.