By Ivy Wong

Urban slums, especially those in developing nations, haven always been a problem that planners have struggled to address and remediate. The slums of Nairobi are no different. Nairobi is a relatively new city, only established around a century ago. However, the number of slums grew at an exponential rate, while the living conditions became worse just as quickly. One could say that the actual living conditions of slum-dwellers in Nairobi are not much different from the dramatized depictions in movies. In Nairobi, the 2.5 million slum dwellers represent 60% of Nairobi’s entire population. Yet, over half of Nairobi’s population lives in only 6% of land (Syrjanen 2008).

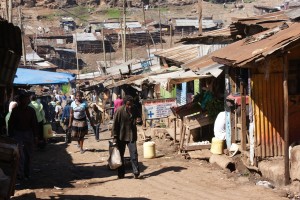

This is a typical residence of a slum dweller in Kibera, Nairobi. These single story homes are made of scraps and sticks. (Image from Nextcity.org)

The question becomes—why do so many people live in slums and how can planners help? In order to answer these questions, we must look at Nairobi’s history and government. Nairobi was under British colonial rule until the 1960s and was largely segregated into areas based on race (inventory). Once they gained their independence, the Africans took over the Nairobi City Council. However, they did not have much experience or education to properly govern the city; many officials often gave jobs to friends, relatives or important constituents (Werlin 2006). The government became very corrupt—large sums of money disappeared and in fact, Kenya lost about a fifth of its GDP due to corruption in 2002 (Werlin 2006). A corrupt government also ends up taking away resources from the public and those who suffer are the urban poor. The government failed to provide public services such as waste collection, causing waste to be dumped in open drainage channels, leading to disease and flooding. In addition to a very corrupt and inadequate government, independence in 1963 encouraged rural to urban migration, which also led to an increase in the demand for housing and the growth of slums in Nairobi.

Others argue that the slums are perpetuated African urban poverty. Often, when one is born into poverty, it is very hard for him to escape the ‘cycle of poverty’. The poor lack the resources and money to buy their own land or house and resort to illegal squatting. A large poor population means that there is a large, and growing, group of illegal squatters. Others will Kenya’s heavy international debt, structural adjustment programs imposed by the World Bank and IMF, and inadequate foreign aid (Werlin 2006).

It is important to try to target the causes of these slums and even more important to look at past examples of attempts at slum-upgrading. The Vagrancy Act of 1949, was a form of slum-clearance that allowed the government to remove or relocate any ‘vagrants’ to a different area if they had not found any employment after three months. From then on, government housing policy has been very harsh towards Africans and had the goal of keeping them out of Nairobi. The Kenyan leaders continued their policy of slum demolition, using the Public Health Act to justify their actions (Macharia 1992). Slum clearance would only produce temporary effects; the large mass of population that became displaced would eventually have to find new housing. Since most of them were poor, the obvious reason would be that they squat in another area. In the 1960s, the World Bank and USAID officials advocated low-income housing in Nairobi that would provide water, sanitation, public transportation, and schools. This would be done through the encouragement of ‘self-help’ housing or sites-and-services schemes (Muwonge 1980). However, the government opposed because they felt it would spoil the beauty of the city and would bring too many people into the city. The Nairobi City Council was largely ineffective in promoting home ownership, and thus were unable to prevent further growth of slums (Werlin 2006).

Housing and settlement policies in Nairobi are also very constraining and limiting. The demolition policies leave low-income areas very inaccessible to new migrants. There have been efforts made to encourage residents to migrate to suburban or peripheral areas, especially using self-help housing policies (Muwonge 1980). However, housing developments on the periphery still were too expensive for the extremely poor. The qualifications of loans for those who could live in those housing developments were also very high; for example, for one to qualify for a loan, the house needed to be built to a sufficiently high standard. As a result, the opportunities of slum-dwellers and the urban poor are limited and shaped by the housing policies of Nairobi (Muwonge 1980).

Hundreds of residents in informal settlements near Mitumba in Nairobi were left homeless after slum demolition. (Image from Daily Nation).

The continual growth of slums is a problem that cannot be solved overnight. The root of the problem lies in Nairobi’s history, ever since it’s Independence from Britain and has continue to manifest itself in different factors, such as urban poverty, corrupt government and ineffective policies. Slums can be one of the ‘wicked’ problems that there can be no one step solution for. It requires both time and resources in order to truly impact all the underlying causes and problems. Ethical questions also present themselves in trying to intervene. Yet, we should not give up hope in aiming for a better future for these slum dwellers and their future generations.

Part II: Current Slum Upgrading Initiatives in Nairobi: Successes and Challenges

Bibliography

Macharia, Kinuthia. “Slum Clearance and the Informal Economy in Nairobi.” The Journal of Modern African Studies. no. 2 (1992): 221-236.

Muwonge, Joe Wamala. “Urban Policy and Patterns of Low-Income Settlement in Nairobi, Kenya.”Population and Development Review. no. 4 (1980): 595-613.

Werlin, Herbert. “The Slums of Nairobi: Explaining Urban Misery.” World Affairs. no. 1 (2006): 39-48.

Syrjanen, Raakel. UN-Habitat and the Kenya slum upgrading programme : strategy document(Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlement Program, 2008).