Guest post #3 by Lynn Braband, retired from our NYSIPM Program but still part of the ‘family’. Lynn’s career experience with wildlife management AND IPM led him to prepare blog posts that addressed the issues faced by wildlife managers in protecting properties while promoting wildlife. Can managing damage also benefit wildlife conservation?

In four posts, Lynn addresses: relevance to a changing society, motivation to preserve habitats and species, conflict with highly valued and economically important wildlife species, endangered species protection, and ecosystem integrity. See Post One and Post Two

“You don’t send it to heaven, do you? It’s not its time to go to heaven.”

“I don’t want you to try anything unless you can kill them all.”

These two perspectives, from actual conversations that I have had with individuals about conflicts with wildlife, illustrate that people are concerned, often with varied motivations, about the techniques used in seeking to resolve wildlife-human conflicts. In my previous blogs, I surveyed how resolving human-wildlife conflict is important to wildlife conservation and the questions that wildlife damage professionals (and the general public) need to address when confronted with situations when wild animals come in conflict with human interests.

Today, I wish to briefly discuss the approaches and techniques that wildlife damage professionals utilize. While it would take a whole course to do justice for all of the techniques available, I will define major categories giving an example or two for each. The following “taxonomy” is adapted from Michael Conover’s Resolving Human-Wildlife Conflicts; The Science of Wildlife Damage Management.

Modifying human behavior

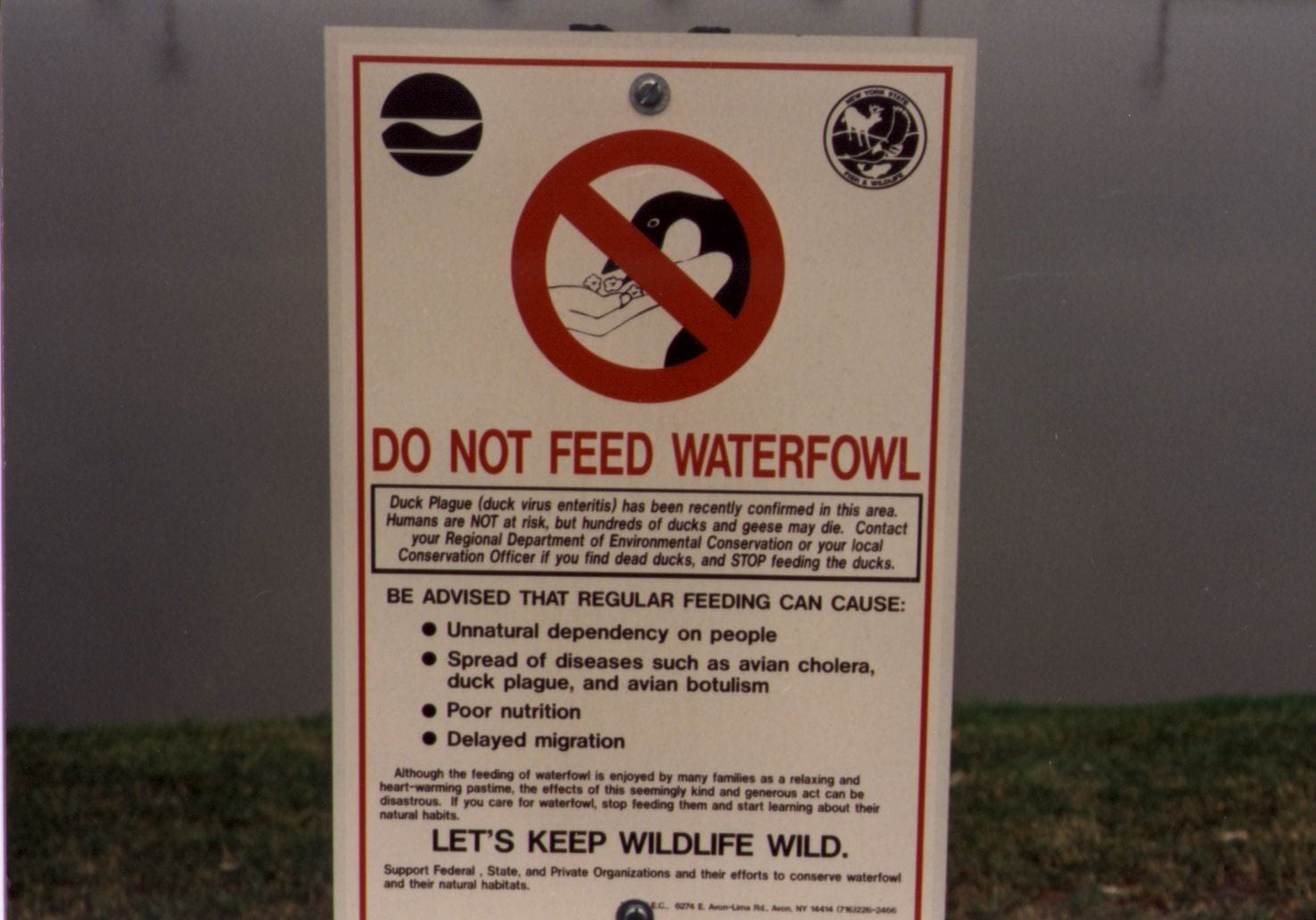

This is often attempted with a combination of education and regulations. For example, signs prohibiting the feeding of geese and other birds are commonly posted by ponds in parks and malls, and almost as commonly ignored. Chances for success can be improved with planning follow-up beyond simply posting signs. For example, one municipality recruited volunteers and interns to patrol the parks and explain to people the reasons behind the regulation.

Educational outreach that is limited to encouraging simple toleration of wildlife probably has limited effect. People vary on what they are willing to tolerate. An apple farmer may be less tolerant of deer than a hay farmer whose crop may be less regularly damaged. A homeowner may enjoy seeing raccoons in her yard, but not when they take up residence in the attic.

Lethal control

Most commonly this is by mechanical means as trapping or shooting. With the exception of rats and mice, there are few pesticides (besides repellents) legally available for use on wild animals. Numbers of the endangered Kirkland’s Warbler kept dropping despite intensive habitat management until invasive cowbirds, which parasitize the warbler nests, were mass trapped and euthanized. Introduced nutria, a large aquatic rodent native to South America, were destroying vast areas of marsh in the Cheaspeake Bay. Federal biologists systematically captured and destroyed the animals resulting in the wetlands beginning to be restored.

Fertility control

A complicated and on-going area of research, “fertility control is not a panacea for all human-wildlife conflicts, but it can be used to reduce some wildlife populations” (Conover). However, the long-term effects, including behavioral, need to be understood. Much work, largely still experimental, is being done with immunocontraception in species as deer. OvoControlâ is a fertility control product registered for pigeons. Attempts at fertility control may also be physical/mechanical such as addling or oiling goose eggs.

Wildlife translocation

Translocation, or relocation, refers to the capture, removal, and release of animals in a different location. This method often appeals to the public but has many problems including the potential for disease transmission, stress on the relocated animal, moving the damage to a new locality, and return of the animal to where it was captured. Conover states that translocation may be appropriate when the animals have a high value as an endangered species, the population is below carrying capacity at the release site, or public relations concerns outweigh other considerations.

Next time: fear-provoking stimuli, chemical repellents, diversion, exclusion, and habitat manipulation.