We can’t leave out diseases. Let’s go back to the cover crop. One potential downside to growing organic rye is ergot infection. Claviceps purpurea is a parasitic fungus that can infect rye and other cereal crops. The sclerotia of the ergot fungus contains alkaloids which can be fatal to livestock and humans if ingested. Scout for a honeydew being produced from the flowers, and the sclerotia (pictured) after anthesis is complete—like this in early-to-mid July.

A large range of grasses can host C. purpurea, so mowing wild grasses and crimping rye before they begin seed production will decrease the rate of infection in your fields.

Powdery Mildew, a fungal pathogen that lives on the surface of leaves, sends little feeding structures into the leaf to absorb carbohydrates and other nutrients. It’s the predominant disease in squash production, occurring every season in both summer and winter squash, as well as pumpkins (many varieties of cucumber and melon are resistant). Unlike many fungal plant pathogens, it’s inhibited by leaf wetness. Instead, high humidity is what favors powdery mildew.

Powdery mildew reduces crop yield and quality by causing leaves to die prematurely, which results in smaller and less-sweet winter squash. Resistant varieties and fungicides are the main methods for controlling powdery mildew. Bush Delicata, the variety we’re growing in our trial, has some tolerance. Half of each of our plots is being treated for insect and disease pests with insecticide or fungicide that is allowed for certified organic production. Because the pathogen produces a lot of spores and increases quickly once infection starts, the recommended threshold for starting fungicide applications is one infected leaf per 50 leaves scouted.

We used a potassium bicarbonate product in this trial, but there are other allowed products that have been shown to be effective, including botanical oils and soap-based products. We’ll be comparing yield and quality (soluble solids in the fruit) between our treatments and between our treated and untreated subplots. Our scouting so far has shown lower levels of disease in our treated plots.

So how did the season go?

On Monday 9/20/21, coincidentally, the same day as the 2021 Harvest Moon, we collected the last round of our squash harvest data. Here are our yield results:

The total mass of squash fruit includes everything marketable and unmarketable. Black plastic mulch with drip irrigation appears to have yielded the most, with cultivated bare soil close behind. Straw mulch yielded less, and our rolled rye treatments resulted in 100% crop failure.

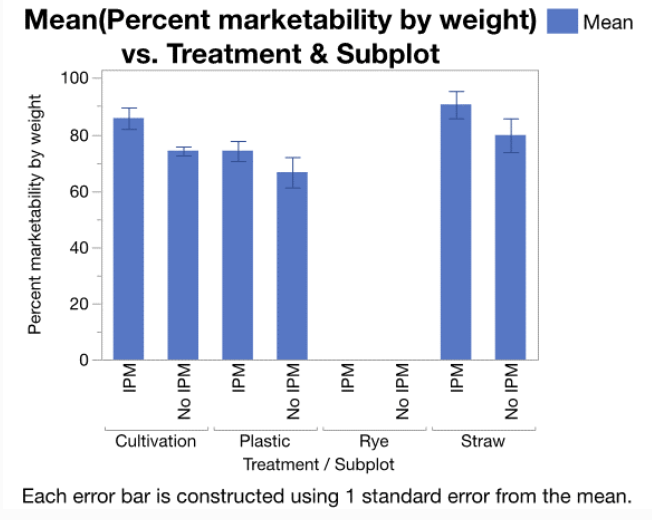

Marketable yield includes only those squash without rot, wounds, or other defects. The subplots which received organic pest management sprays based on IPM thresholds generally produced more marketable yield than untreated subplots.

The percentage marketability was perhaps boosted in the straw mulched treatment by the cleanliness of the fruit, but this was also the first treatment to mature, so it was harvested a few days ahead of the others and had less time to subjected to probing insects and pathogens.

This series of posts looks at a 2021 field trial by NYSIPM’s Bryan Brown, Marcus Lopez, and Abby Seaman. For full details, read their complete posts throughout the season.: