by Carole Liantonio, Warwick Senior Master Gardener Volunteer

The princess or empress tree (Paulownia tomentosa) is a fast growing shade tree that was as introduced to North America from Asia via Europe in the 1800s. As it is a beautiful tree with many desirable characteristics, the princess tree is widely available commercially and frequently planted.

Let’s take a look at why people are planting it and why that is problematic.

The Good News:

The princess tree is one of the fastest-growing trees in the Northeastern United States. It can grow 10 to 20 feet in a single year, reaching 80 to 100 feet in a decade. This explosive growth is accomplished by pulling carbon dioxide out of the air more efficiently than any other woody plant in the world. Photosynthesizing beyond the call of duty could be a huge help in sequestering carbon and assisting in our struggles with climate change.

In addition to extra-efficient carbon sequestration, the wood from the princess tree has many uses. It is lightweight, like balsa, but has a very high strength-to-weight ratio. It can be carved, holds nails and screws without splitting, and doesn’t warp or change shape when dried. It has been used for surfboards and kayaks, chests, boxes, clogs, musical instruments, and touring skis, and it’s burned to make charcoal for sketching. The wood is highly prized and worth more per linear foot than black walnut, oak, or maple. It is not surprising that in Japan, where the tree is native, a princess tree was traditionally planted at the birth of a daughter to ultimately be used for her wedding dowry!

The princess tree is also ascetically pleasing. In late spring, it is covered with large clusters of purple to white trumpet-shaped blooms. These foxglove-like blossoms emit a honeysuckle-like fragrance. Then a few weeks after bloom the tree is covered with large heart-shaped leaves.

Does this sound too good to be true?

The Bad News:

Despite all of its favorable qualities, the princess tree also causes significant problems. Each of the lovely flowers it produces contain thousands of tiny winged wind dispersed seeds. When they land in disturbed areas with plenty of sun and good drainage, such as roadsides, old fields, forest edges, or disturbed riverbanks, they will germinate and thrive. This propensity to establish in disturbed areas displaces native species and alters the ecological community. Once established, the princess tree competes with native plants for nutrients and water. It also produces a dense shade making it difficult for native plants to grow underneath it. And because the roots of the princess tree also grow at an incredible rate, they can burst apart foundations and walls.

Fifteen states, including Pennsylvania and Connecticut, have listed the princess tree as invasive and/or have laws regulating its sale. Although not regulated as an invasive species in New York State, the princess tree has a NY Invasive rank of “moderate” meaning that care needs to be taken to remove it from natural areas, and that it should not be used in parks and preserves with significant environmental value. In our area, the Lower Hudson Partnership for Regional Invasive Species Management (LHPRISM) considers the princess tree as “established”.

Once a princess tree establishes itself, it is very hard to control. It is a resilient tree that reproduces asexually through root suckers that are capable of growing up to 15 feet in a single year. When trying to remove a princess tree, if any root fragment is left in the ground, the tree will re-establish itself very quickly. For this reason, mowing small seedlings is not a viable method for removal. Unless the stump is chemically treated, re-sprouting can also occur when large trees are cut down.

A Compromise?

Tree farmers and specialty nurseries are currently exploring princess tree hybrids, which have many of the attributes of Paulownia tomentosa but have not yet been found to be as invasive. They include Paulownia shantong (P. tomentosa × P. fortunei) and Paulownia elongata. With any luck, these hybrid species will beautify the spring landscape without breaking the pavement or becoming a royal pain in the neck!

Identifying the Princess Tree in the Field

Learn More

Paulownia tomentosa – Lower Hudson PRISM

Paulownia tomentosa – North Carolina State Extension

Princess Tree – National Invasive Species Information Center, USDA

The Fastest Growing Trees in the Northeast – Shelterwood Forest Farm

Note: The article ‘The Fastest Growing Trees in the Northeast’ incorrectly states that Paulownia trees such as the princess tree use C4 carbon fixation. Learn more about this common misconception.

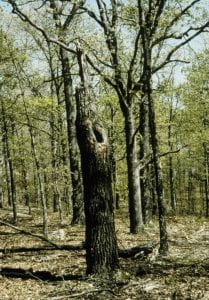

Did you know a dead or dying tree is called a snag and that snags serve a vital purpose in the ecosystem? I never seriously considered that until attending a webinar presented by Gillian Martin on

Did you know a dead or dying tree is called a snag and that snags serve a vital purpose in the ecosystem? I never seriously considered that until attending a webinar presented by Gillian Martin on

Holly (Ilex spp.) provides deep green and rich red color for the winter season. There are many species of holly including our native

Holly (Ilex spp.) provides deep green and rich red color for the winter season. There are many species of holly including our native

Poinsettias are an attractive green plant most of the year and come late spring they can be brought outside and either kept in containers or transplanted into a part-sun garden that gets four to five hours of sun a day. Getting your green poinsettia to change color for the holiday season is an onerous task and requires excluding light from the plant for period of time while still keeping the plant healthy.

Poinsettias are an attractive green plant most of the year and come late spring they can be brought outside and either kept in containers or transplanted into a part-sun garden that gets four to five hours of sun a day. Getting your green poinsettia to change color for the holiday season is an onerous task and requires excluding light from the plant for period of time while still keeping the plant healthy.

The

The

Corn is one of the

Corn is one of the  The eastern white pine is a very large tree, fifty to eighty feet tall and twenty to forty feet wide. It can often be identified by its lone silhouette as it towers over other trees in the forest or by its wide base and gradual layering of upswept branches up to the top.

The eastern white pine is a very large tree, fifty to eighty feet tall and twenty to forty feet wide. It can often be identified by its lone silhouette as it towers over other trees in the forest or by its wide base and gradual layering of upswept branches up to the top.  Somewhere between 25-35 million live Christmas trees are sold in the United States each year. When grown as a Christmas tree, the eastern white pine is cut at six feet and is usually sheared. It takes 6-8 years to produce an eastern white pine Christmas tree whereas it takes other an average 15 years for other Christmas tree species making it very profitable for Christmas tree growers.

Somewhere between 25-35 million live Christmas trees are sold in the United States each year. When grown as a Christmas tree, the eastern white pine is cut at six feet and is usually sheared. It takes 6-8 years to produce an eastern white pine Christmas tree whereas it takes other an average 15 years for other Christmas tree species making it very profitable for Christmas tree growers.

One of the most recognizable symbols of fall is a branch of oak leaves and a couple of acorns. Oak trees (Quercus spp.) have been around for approximately 55 million years old, with the oldest North American specimen being 44 million years old. Long before pumpkins and corn stalks came to symbolize harvest and bounty, people depended on the humble acorn and majestic oak tree for sustenance and shelter. Today we think of oak trees in terms of shade, firewood, and sturdy furniture, but as acorns can be stored for long periods of time and the flour made from them is quite nutritious for thousands of years acorns were the main food staple for people in

One of the most recognizable symbols of fall is a branch of oak leaves and a couple of acorns. Oak trees (Quercus spp.) have been around for approximately 55 million years old, with the oldest North American specimen being 44 million years old. Long before pumpkins and corn stalks came to symbolize harvest and bounty, people depended on the humble acorn and majestic oak tree for sustenance and shelter. Today we think of oak trees in terms of shade, firewood, and sturdy furniture, but as acorns can be stored for long periods of time and the flour made from them is quite nutritious for thousands of years acorns were the main food staple for people in

When all environmental factors work together, oak trees can produce an overabundance of acorns in what scientists call a “

When all environmental factors work together, oak trees can produce an overabundance of acorns in what scientists call a “

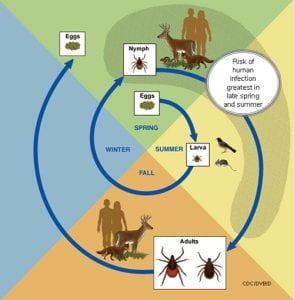

Do a daily

Do a daily Dump out any standing water from containers in your yard to prevent mosquito breeding.

Dump out any standing water from containers in your yard to prevent mosquito breeding.

Most vegetable plants need about

Most vegetable plants need about