The New York City Subway is a cultural icon and an institution. It is also the most extensive and well-utilized transit system in the world. In terms of size, 660 miles of track connect the subway’s 469 stations (Waterloo 2010). Additionally, the subway provides 5.9 million rides to residents in and around New York City on a daily basis (Waterloo 2010). This makes the New York City Subway the busiest transportation system in the western world.

Due to its magnitude and popularity, the subway has significantly influenced contemporary development in New York City. Subway driven growth is so profound that it has virtually dictated development patterns in Upper Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Queens (Zimmerman 2015). As the subway’s expansion extended to the city’s limits in the 1960s, New York’s suburbs were also impacted and development was forced to adjust accordingly. Thus, it is not baseless to claim that the subway system transformed New York from an overcrowded port to a globalized metropolis. Why? The evidence to support this argument is right here. All one needs to do is simply read this article and examine the subway maps provided. Then it will be clear how New York grew into the great city it is today.

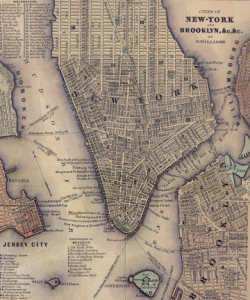

Before one can begin to understand how New York became its contemporary form a bit of background information is required. The 1800s was a century of western migration. During this period, waves of immigrants arrived in hoards to ports along the east coast. The most popular destination was New York City. In the ten years between 1850 and 1860 the cities population doubled to reach over one million residents (Waterloo 2010). The majority of these immigrants lived in vertical slums called tenements on the southern tip of Manhattan. Within tenements were sweatshops, communal kitchens, and inadequate sanitation facilities (Jacobs 2012). These features threatened the health and safety of its residents.

After the conclusion of the Civil War, housing reformers and businessmen started to confront the horrific tenement conditions. The invention of the camera helped in the push to exhibit the devastating state these slums. After a significant amount of outcry from these images, municipal officials were persuaded to pass legislation for building codes in 1867. Although the codes required adequate light and ventilation for each housing unit, tenement owners largely refused to change their ways (Waterloo 2010). Migrants had no choice but to continue living in abject poverty.

As conditions got intensively worse for the immigrant population, urban elites became restless. The wealthy worried that disease, crime, and alcoholism in the poor districts would spill over into the more “decent” neighborhoods of Manhattan (Waterloo 2010). Thus, those who were wealthy began moving north. Doing so shifted the fashionable neighborhoods away from industrial and market zones, creating a more polarized city.

The impact of elites fleeing north caused city officials to question what would happen if tenement dwellers did the same. During the late 1800s lower Manhattan was so crowded that delivery wagons could barely maneuver the streets. As subway historian Stanley Fischler wrote, “as early as 1962…it was evident that the city was hopelessly snarled in traffic and had to find some form of relief” (Waterloo 2010, pp. 8-9) That relief would come by giving tenement dwellers alternative housing opportunities on vast tracks of land north of Lower Manhattan and also in the Bronx. But before housing in these areas could be occupied, a rapid transit system like the London Underground was necessary (Haberman 2006).

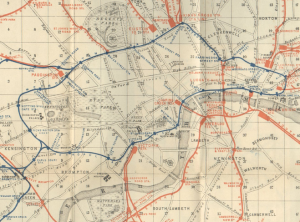

In 1850 London faced a similar housing crisis. To resolve rampant overcrowding and congestion within the city, London officials constructed the first underground transit system in the world. The premise was to push the urban poor to the periphery of the city while still allowing them to commute to the center (Haberman 2006). For the most part the system was a success. The Underground’s well ventilated tunnels and passages did not significantly impact London’s built environment. Reformers in New York appreciated this quality and wanted to implement a similar system (Zimmerman 2015). First, though, the project had to be designed, engineered, and won politically.

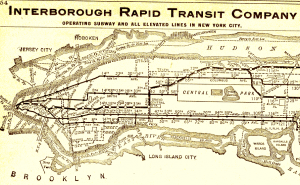

|

| Figure 3. The first official map of the Interborough Rapid Transit system, which would later become part of the New York City Subway (Gizmodo 2013) |

It took forty years for the City to pass legislation for authorizing the subway. This delay was due to multiple factors including opposition from Boss Tweed’s political machine in Tammany hall as well as issues engineering around Manhattan’s complicated geology (Zimmerman 2010). Everything changed on March 24,1900. It was on this date that William Barclay Parsons, a graduate of Columbia and co-founder of the engineering firm Parsons Brinkerhoff, and August Belmont, financer of the privately owned Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT), broke ground on the project. The IRT was a precursor to the New York City Subway system.

Because engineering the underground rail system was such a massive feat, the project had to be divided into phases. The first phase included 21 miles of track, the majority of which was underground (Waterloo 2010). The route started at City Hall and then proceeded north to Grand Central Terminal. Afterwards it hung a sharp left and continued under 42nd Street to Broadway. The meeting of these streets would eventually be known as Times Square. Following Broadway, the line then continued north up to 96th street. Despite its length and complexity, this line took only four and a half years to complete. On October 27th 1904 the IRT opened to the public. The fare was a nickel (Zimmerman 2010).

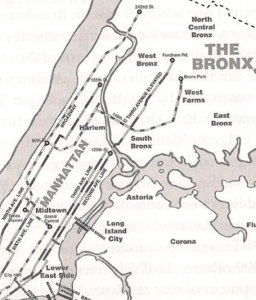

|

| Figure 4. Map of rail lines in New York in 1910. Note the route of the first subway system, which is described in the paragraph above (Waterloo 2010). |

The completion of the IRT afforded the opportunity to move out of Lower Manhattan. The reasoning for migrating north was quite simple. The IRT was convenient. A combination of express and local trains enabled riders to travel the full length of the line in under an hour. They could live in uncongested neighborhoods while still being able to travel to their jobs in lower Manhattan. The ability to commute was revolutionary (Campbell-Dollaghan 2015).

With a rapid transit system, New York became a much more desirable city to live in. Consequently the city’s population grew from three to five and a half million between 1900 and 1920 (Zimmerman 2015). But quickly areas in the north of the City were occupied. This forced municipal officials to develop more unoccupied tracts of land (Waterloo 2010). To deal with rapid growth in these new areas, large, speculative apartment buildings were put up. The construction of these buildings, which were primarily above IRT lines, is one of the first historical examples of Transit Oriented Development (TOD) (Campbell-Dollaghan 2015).

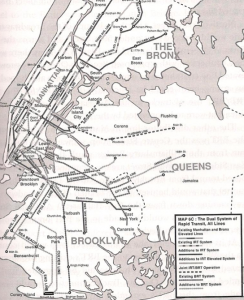

Still, even with the implementation of TOD, there were too many people who lived to the north. Commuting soon became an undesirable experience because the IRT subway cars were overcrowded. Fortunately, the Public Service Commission of New York City came up with a solution. The solution was to connect Brooklyn and Queens to Manhattan and the rest of the city.

In theory, connecting the Boroughs should have been a simple task. Since 1896, the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT) had acquired all elevated and underground lines in Brooklyn and Queens. But the IRT did not want to give up its monopoly and refused to let the BRT expand into Manhattan (Zimmerman 2015). After several years of negotiations, a compromise was met in 1913. The compromise allowed for both the IRT and the BRT systems to expand into all Boroughs.

Known as the Dual System of 1913, the deal between the IRT and BRT consisted of two subway line contracts. The first contract was awarded to the IRT. It gave them full rights to construct a line from Midtown Manhattan to Flushing, Queens. This was a massive project and took close to fifteen years to complete. The second contract was awarded to the BRT. Due to bankruptcy the BRT reorganized as the Brooklyn Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT) (Macdonald 2005). Although the BMT ultimately expanded into Manhattan and the Bronx in mid 1920s their Dual System contract was never completed.

As the 1920s came to a close, The IRT and BMT began to experience serious economic trouble. They, however, were not alone. Due to the onset of the Great Depression, the entire city was falling into financial ruin. To cover expenses, the companies sought to raise transit fairs from the nickel price it had been since 1904. As with most decisions regarding the subway, the political fight raged intensely during the late 1920s (Mindelin 2006). Ultimately they mayor denied companies the opportunity to raise the fare. This forced the IRT into receivership in 1932.

With the IRT on the verge of a financial ruin, the municipal officials sought to consolidate the City’s two rapid transit companies. Mayor LaGuardia led this push and finally won when convinced the city to purchase all the subways in 1940, led this push (Waterloo 2010). Once all the Subway cars and lines were under LaGuardia’s control, the Mayor focused his attention on establishing a single rapid transportation system. Eventually the lines controlled by the IRT and BMT were connected. Having one integrated system under a single authoritative body was beneficial to the city’s residents because it transformed the New York Subway into a civic good. In 1953, the Metropolitan Commuter Transportation Authority (MCTA) was chartered by the state of New York to operate this civic good (Waterloo 2010). The MCTA later changed its name to the Metropolitan Transit Authority or MTA. The MTA still operates the New York City Subway system to this day.

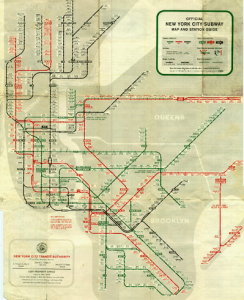

|

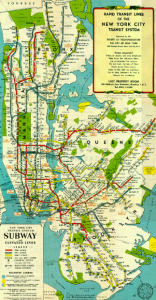

| Figure 7. A subway map from 1959, which is one of the first of its kind after Mayor LaGuardia consolidated rapid transit in New York City (Gizmodo 2013). |

After the chartering of the MTA in 1968, the Authority officially became one of the largest transportation organizations in the world. With this chartering the MTA assumed control of the New York City Transit Authority, the Manhattan and Bronx Surface Transportation Operating Authority, the Long Island Rail Road, and all properties of the Bridge & Tunnel Authority (Mindeln 2006). Having all of the city’s transportation links connected to the Subway spurred development throughout New York’s suburbs. Accordingly, the population of people living in the New York Metropolitan Area increased by 2 million between 1960 and 1970 (Waterloo 2010). This growth established New York not just as a regional city, but a globalized and expanding metropolis.

Although the metropolitan area expanded, the population within New York’s five Boroughs remained relatively stagnant. This population plateau was the result of two factors. The first reason is that there was limited space in New York City for new development to occur. The second reason had to do with the MTA not having the funds to reach these remaining undeveloped areas. Accordingly, plans for new subways lines were drawn up and rejected in the 1970s and 1980s (Badger 2015). It wasn’t until 2008 when approval to expand the New York City Subway was granted.

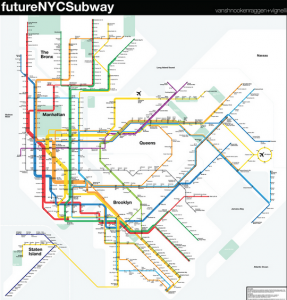

|

| Figure 8. A more contemporary New York Subway Map from 2010. Note the inclusion of the city’s neighborhoods into the design of the map (The Washington Post 2015). |

The intention of this new phase of construction is to spur development on the most eastern and western sides of Manhattan Island. To the East, the Second Avenue T line will consist of a nine-mile tunnel running from 125th Street, Harlem to the Financial District in Lower Manhattan (Plotch 2015). This line will take pressure off the Lexington Avenue 4,5, and 6 trains, which currently are the only subways that service the East Side. The T line will also create a transportation corridor along Second Avenue. The idea is to encourage mixed-use development along it. Eastern Manhattan consists primarily of residential neighborhoods and the City desperately wants to change that trend (Plotch 2015).

On the other side of Manhattan, the extension of the 7 Line has resulted in the redevelopment of the Hudson Yards. This $2 billion project will be constructed over roughly 28 acres of rail yard for New York’s Pennsylvania Station (Shatiel 2015). The new Hudson Yards will consist of 16 skyscrapers. These buildings will include retail centers, cafes, markets, bars, hotels, and cultural spaces between them. The project along with the tunneling for the Second Avenue T line is the largest construction project in the city’s history with one exception. That exception is original IRT subway lines that were constructed under the five Boroughs over 100 years ago (Zimmerman 2015).

Although the future of New York City is unclear, the Subway will continue to grow. This is inevitable because the Subway drives development around the Tri-State Area. Thus, Regardless of the time, effort, engineering, and politics that will go into expanding the massive rapid transit system, the Subway will still persist— continuing to meet the demand of New York City as it has done for the past one hundred years.

Bibliography

Badger, E. (2015, November 9). Why designers can’t stop reinventing the subway map. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/11/09/why-designers-cant-stop-reinventing-the-subway-map/

Campbell-Dollaghan, K. (2013, September 13). 15 Subway Maps That Trace NYC’s Transit History. Retrieved November 12, 2015, from http://gizmodo.com/18-subway-maps-that-trace-nycs-transit-history-1242514280

Elliot, D. (2008). A Brief History of Zoning. In Better Way to Zone: Ten Principles to Create More Livable Cities. Island Press.

Haberman, C. (2009, December 14). No W or Z? Mapmakers, Grab Your Pens. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/15/nyregion/15nyc.html

Jacobs, J. (2012). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. In Readings in Planning Theory (3rd ed.). Blackwell Publishing.

Lynch, A. (2013, May 13). Future NYC Subway. Retrieved November 10, 2015, from http://www.vanshnookenraggen.com/_index/category/maps/futurenycsubway/

Macdonald, E. (2005). Suburban Vision to Urban Reality: The Evolution of Olmsted and Vaux’s Brooklyn Parkway Neighborhoods. Journal of Planning History, 295-321.

Mindeln, A. (2006, September 3). Win, Lose, Draw: The Great Subway Map Wars. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/03/nyregion/thecity/03maps.html?_r=0

Minner, J., & Michev, B. (2013, December 7). Land Use, Transit, and Urban Redevelopment Illustrated (1933-1972): A walk through twentieth century maps from Cornell’s Map Collection. Retrieved December 1, 2015, from https://olinuris.library.cornell.edu/content/land-use

Plotch, P. (2015). Waiting More Than 100 Years for the Second Avenue Subway to Arrive. Journal of Planning History, 309-328.

Shatiel, J. (2015, October 9). Hudson Yards transforming Manhattan’s west side. Retrieved November 13, 2015, from http://www.amny.com/news/business/hudson-yards-development-transforming-manhattan-s-west-side-1.10984273

Waterooo, E. (2010). Under the big apple: A retrospective of preservation practice and the New York City subway system. Cornell Thesis & Dissertations.

Zimmerman, A. (2015, October 22). Why It Was Faster To Build Subways in 1900. Retrieved November 14, 2015, from http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/why-it-was-faster-to-build-subways-in-1900 //www.amny.com/transit/the-mta-s-capital-plan-explained-1.10983914