In college, I fell in love with wildlife medicine and conservation. It’s a tough field to get into though, and at the time I didn’t know if I was really cut out for it. That all changed when I landed the internship of a lifetime with the Jane Goodall Institute at Tchimpounga Chimpanzee Sanctuary in the Republic of Congo. This internship was part of Dr. Robin Radcliffe’s One Health course in partnership with Engaged Cornell and it was the first time it was ever offered. I was the first undergraduate student from Cornell to intern with the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI) in Congo, so I really did not know what to expect. The internship was set up to pair a veterinary student with an undergraduate student to collaborate on a project for the summer. Unfortunately, my partner had a last minute complication and was unable to travel with me. I found this out the same day we were set to travel, just as I was about to catch my flight.

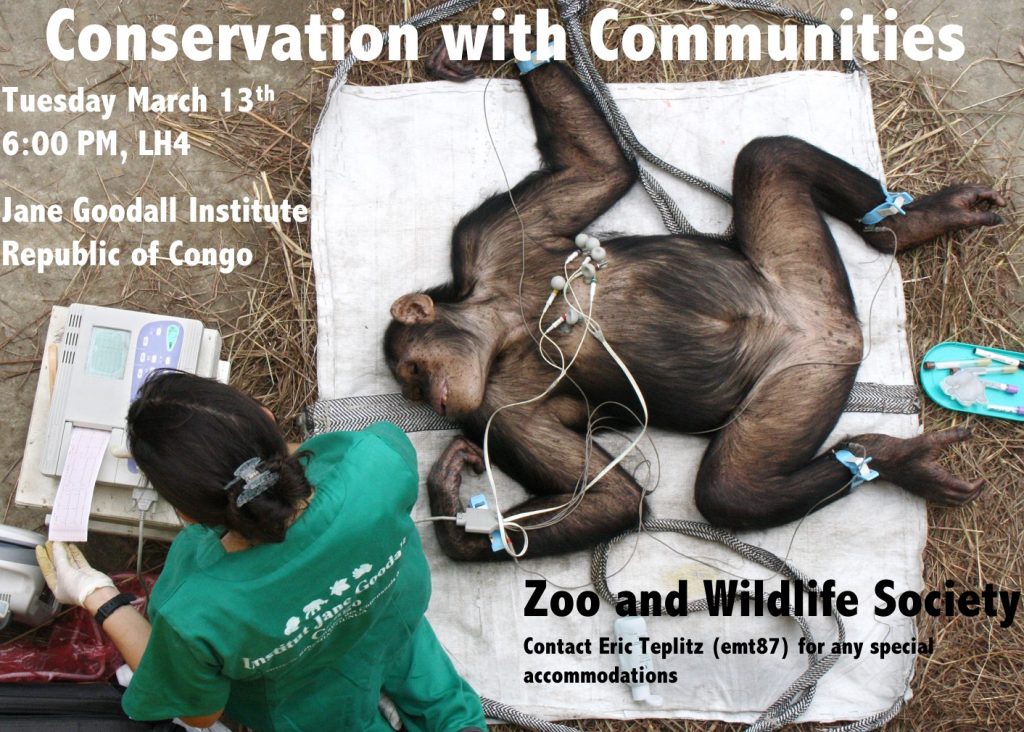

Needless to say, this was not the ideal way to start off my experience in Congo and I would be lying if I said my anxiety wasn’t at an all time high at the thought of having the entire project relying on me. I learned right off the bat that no amount of planning will ever prepare you for a field experience like this. Things can change on the fly so you have to be flexible and roll with the punches. The original project consisted of looking at the cortisol levels of chimpanzees to evaluate at which point in their rehabilitation process they were most stressed. This data would then be used to improve husbandry and rehabilitation practices. This wasn’t exactly what I ended up doing during my time at the sanctuary but I still go a lot out of the experience. In the end, I ended up assisting in several mini projects such as taking measurements of chimpanzees to create a morphometric index to establish malnutrition parameters, taking water cultures of all the sanctuary’s faucets to ensure the water given to the chimps was properly sanitized, shadowing Dr. Rebeca Atencia while she treated several chimpanzee patients and more. I even got to observe a collaring procedure on a Mandrill in the middle of Conkouati Douli National Park–quite literally in the middle of the jungle!

Despite the incredible experience I ended up having, the first two weeks in Congo were quite difficult for me; I was alone, inexperienced, and thousands of miles away from home. I considered going home several times. Being the first student they had ever hosted only further complicated the situation as there was not a fully established program yet. However, I wasn’t about to let the opportunity of a lifetime go to waste, so I tried to make the best of the situation. I had to push myself out of my comfort zone like never before. I taught myself many things, such as how to work a portable autoclave, how to make my own cell culture medium, and even some basic microbiology from old books the vet kept in the lab. Another big challenge I faced was communicating with the sanctuary staff. This was difficult because not many of them spoke English, so I had to overcome a cultural and language barrier. Thankfully, I was somewhat proficient in French, and this helped me to communicate with my Congolese colleagues.

Despite all the personal challenges, the good definitely outweighed the bad. The friendships I made, both human and non-human, were what got me through those initial tough times. Every morning I would start my day by walking around the sanctuary to say good morning to the chimps. In time, I came to know every single one by name and learn about their unique personalities. Some of the chimps I connected to most were Alex, Mbebo, Betou, Lemba, Lounama, Falero (the baby of the bunch), and my favorite gal, Youbi.

These animals taught me so much about human instinct, and the more time I spent with them, the more I realized just how much they have in common with us. I learned how incredibly intelligent they really are, how cruel they can be, but also how kind and nurturing, not to mention hilarious. The more time I spent with these animals the more it confirmed that wildlife/conservation medicine was the field for me. Though I still questioned if I had what it took, I got my answer one night when Youbi came into my life.

One evening, the sanctuary was on high alert as we were to receive a new chimp from another sanctuary. This was Youbi. I remember the first time I saw her, she looked so tiny and fragile, could barely move and was basically a bag of bones. She was severely malnourished and anemic, as we soon found out. Youbi required an emergency blood transfusion. Dr. Rebeca Atencia, the head veterinarian selected Tchamaka as the donor, a strong, beautiful male chimp that lived at the sanctuary. We gave Youbi the transfusion, but were unable to anesthetize her fearing she wouldn’t wake up from anesthesia. Instead, some of the staff and I had to hold her down using our own strength. Chimpanzees are about four times stronger than the average person, so despite the extreme level of malnutrition/weakness she was in, it still took all the strength I had, plus that of another staff member to subdue Youbi while she received the transfusion. That transfusion worked wonders! It was as if with every drop of blood, Youbi regained a little bit of life back. For the next couple of days, I was tasked with feeding her, giving her her medicine, and providing enrichment. We would inject protein powder and iron supplements into all her food and after a few days she had the strength to move about the room.

Youbi and I formed a bond like no other I have ever experienced. Being with her and taking part in her rehabilitation made me realize that I definitely have what it takes to thrive in this field. It gave me a renowned sense of purpose and I knew then that I had found my calling. This was an experience I will never forget. I will always treasure the memories of my time in Congo. I am so thankful for having had this opportunity.

You must be logged in to post a comment.