When one thinks of Indonesia, picturesque scenes of Bali’s beaches or bold batik patterns might come to mind. Indonesia has an entirely different meaning to me, as this archipelago constitutes one of the most biodiverse regions on the planet. Amidst the dense rainforest foliage are fascinating endemic species, but given threats from habitat loss and poaching, the future of some Indonesian species remains uncertain. In particular, Javan and Sumatran rhinoceroses exist in a precarious state, being some of the most endangered mammals in the world. Last summer, I had the privilege of traveling to Indonesia with Carmen Smith (DVM 2021) and Montana Stone (BS 2019), under the guidance of Dr. Robin Radcliffe and support from Expanding Horizons and Engaged Cornell, to partake in a multi-faceted program centered around international conservation efforts.

Building upon Dr. Radcliffe’s well-established relationships with partners in Indonesia, we were warmly welcomed by personnel from WWF-Indonesia, who had created a summer schedule with the goal of exposing us to different components of conservation work. First, we headed to the buffer zone of Ujung Kulon National Park, the last habitat of the Javan rhino. We assisted a group known as Sekala Petualang as they led conservation education programs for local school children where mainly Indonesian was spoken. It became quickly apparent that the weekly Indonesian classes we took during the spring semester before leaving were my only saving grace in that remote part of Indonesia (where cellular signals are nonexistent). Environmental stewardship was the underlying theme to the program, as educating children is an effective way to create a conservation-embracing culture. Despite living alongside a national park with Javan rhinos, a number of children were unaware that such an animal even existed in their “backyard”. It was heart-warming to see that the kids had open and receptive minds. One of Carmen’s presentations introduced veterinary medicine, yet another unfamiliarity that intrigued them. This segment of the summer underscored the importance of engaging with communities, walking in their shoes, and creating a space conducive for exchanging ideas bidirectionally.

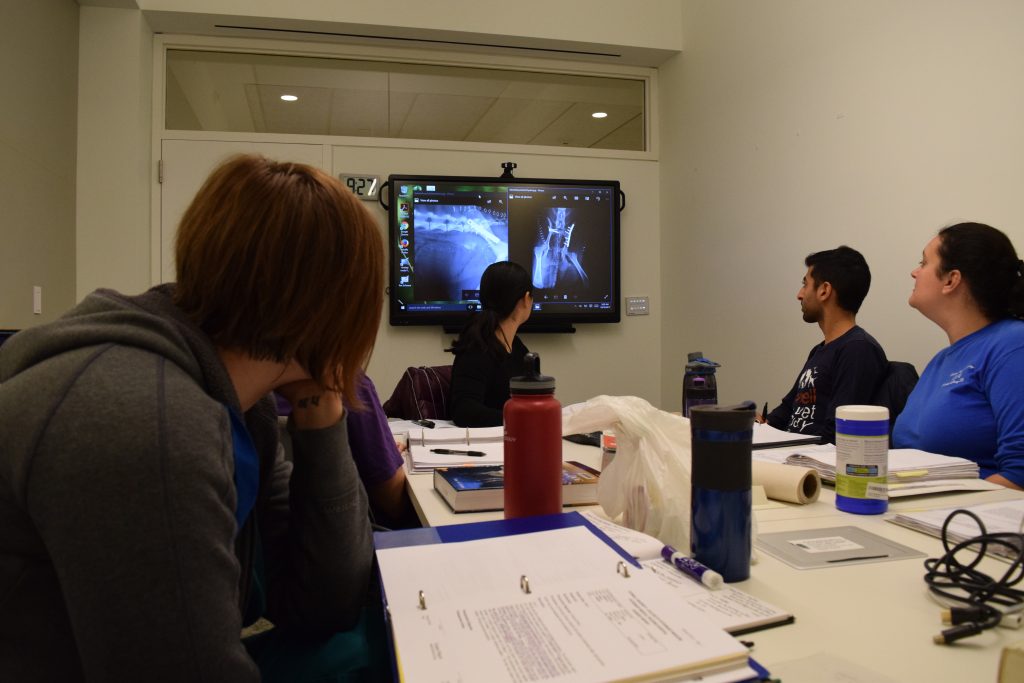

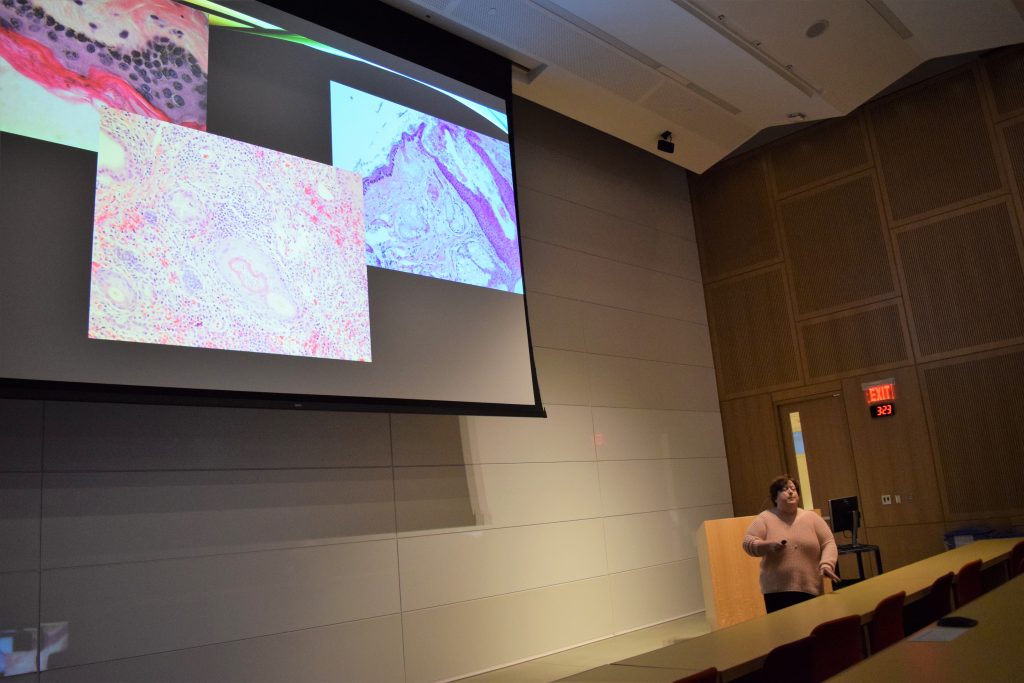

The next portion of the summer was spent at Institut Pertanian Bogor, a prominent university, which brought us back to the hustle and bustle of Indonesia’s urban scene. The crux of Carmen’s Expanding Horizon’s project was investigating rhino pathology as a means to better inform rhino conservation initiatives. The pathology faculty were very generous with their samples, taking us through both Javan and Sumatran rhino mortality cases. Despite my ineptitude with pathology, I was able to gain an appreciation for the challenges pathologists face working with wildlife species. I soon learned what the word “autolysis” meant as we scanned each image from the necropsy; imagine the difficulty of mobilizing a team of pathologists that must trek with their supplies to remote sites within the rainforest, finally laying their hands on the deceased rhino more than a day post-mortem, precious tissues vulnerable in the incessant Indonesian heat.

Ultimately, Carmen and I were able to translate pathology reports into English to increase their accessibility, perform literature reviews, and identify topics worthy of discussion for a scientific publication. We realized that while individuals may have a species’ best interest in mind, other parties are bound to have conflicting interests or political underpinnings that ultimately jeopardize cohesive collaborations between various conservation organizations. We learned that any work of such nature, especially in a foreign country, must be done with exacting precision and respect. This chapter of the summer would be incomplete without mentioning my bout with dengue fever, which actually made me miss a portion of the pathology work. What started as a simple cough turned into body aches, fever, inappetence, and more. I figured an illness was inevitable in a novel tropical country, so I thought this was normal (despite running out of all of my pain medication trying to ease the symptoms). Soon thereafter, Montana also fell ill with dengue, at which point I was tested. Although no one heads off to international experiences with the intention of contracting a mosquito-borne disease, the experience was a lesson in resilience and preparedness. After all, despite being ill, I was unable to turn down a day trip to Taman Mini, a phenomenal bird park!

Prior to the next portion of the program, we briefly visited an illegal pet market, which unnerves me still to this day. I had a mental image of what such a market would entail, though nothing could have prepared me for the true horror I saw. Densely packed cages teeming with stressed birds (not to mention the dead birds littering the cage bottoms) were interrupted by cages of civets, flying foxes, macaques, and more. My heart ached for the bird that would not live to see another sunrise, for the listless civet lying motionless in its cage, and for the chained baby macaque tucked away in the shadows. I felt defeated, but I realized that such scenes are the very essence of what drives me and many other veterinary students to pursue careers that contribute to the conservation of wildlife. This experience solidified why educating the next generation on the importance of conservation and environmental stewardship is essential.

With the atrocities from the market still fresh on our minds, Carmen and I went to International Animal Rescue – Bogor, a site that primarily focuses on rescue, rehabilitation, and release of Javan and Sumatran slow lorises. Lorises are common in the wildlife trade, and in the markets, their canines are clipped, setting the stage for dental and subsequent metabolic disease. A number of the lorises we worked with were non-releasable, so the rescue exceeded twice its anticipated capacity. We engaged in loris husbandry, spent nights observing lorises (an experience unlike any other!), and helped with their veterinary care. Multiple patients illustrated the harsh reality of a fragmented habitat. The mere existence of a road bordered by uncoated electrical wires poses a great threat to unsuspecting lorises attempting to cross the road. The prognosis is often bleak for the few lorises that manage to survive electrocution. This experience solidified my understanding of the human/wildlife dynamic, which tragically tends to swing in favor of the former.

Habitat loss and fragmentation set the stage for the next experience that brought us to Kelian Sanctuary in Borneo. The previous year, a Sumatran rhino named Pahu was rescued from the wild and brought to the sanctuary. Pahu is possibly only one of three rhinos remaining of her subspecies, so it is of utmost importance to rescue these isolated animals and investigate breeding options. There are Sumatran rhinos (Sumatran subspecies) that reside at the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary in Sumatra, so collaboration is anticipated in an attempt to save this species overall. As we landed in Borneo in a precarious propellor plane, the three of us were riddled with excitement. In the few days we had at Kelian, the team composed of individuals from WWF-Indonesia and ALeRT completely immersed us in the operations at the sanctuary. Before I knew it, I was hand feeding Pahu various plants, watching her veterinary examinations and procedures, and observing her in her paddock. It was at that moment that it was clear to me that megafauna like the Sumatran rhino simply cannot be lost from this planet—it is our duty to fight with all of our passion and intensity to save such species before they slip away. Even when I was out with the team collecting food for Pahu or planting trees in the rainforest, I embraced the physical and acoustic beauty of the surrounding rainforest. During patrols of Pahu’s paddock, I witnessed gibbons, macaques, hornbills, and even a clouded leopard. During this time, Montana was able to train personnel at the sanctuary to utilize a Cornell Lab of Ornithology Swift recorder to document Pahu’s vocalizations, as no bioacoustical analysis had previously been done on Sumatran rhinos. To this day, I treasure hearing a content Pahu wallowing in the mud, “humming” and producing kazoo-like sounds, and I hope that one day everyone will know of this rhino’s plight and hear their delightful vocalizations.

As I write, I wonder whether that was my first and last time working with a Sumatran rhino. Let me re-phrase that—will the next generation even learn of critically endangered species like the Indonesian rhinos or will the species’ names be relics of a bygone era? Questions like these serve as an impetus for my passion in conservation medicine. My time in Indonesia helped me grasp what international conservation work entails, exposed me to the associated difficulties, all while leaving me inspired. I met some of the most passionate individuals in Indonesia, so I have faith that my previous questions will have favorable responses decades from now.

Greetings from Otjiwarongo, Namibia! My name is Elvina Yau and I am a rising 3

Greetings from Otjiwarongo, Namibia! My name is Elvina Yau and I am a rising 3

Maison Scheuer is the 2022-2023 WildLIFE Blog Editor and a proud member of Cornell ZAWS. Her

Maison Scheuer is the 2022-2023 WildLIFE Blog Editor and a proud member of Cornell ZAWS. Her