The conservation of forests and wildlife is becoming increasingly important around the world due to human interference and the rising number of endangered species.

Currently, many practices involved in the monitoring, tracking and protection of wild animals involve time-consuming, resource heavy processes. New, sustainable solutions for conservation are needed to safeguard wildlife effectively in the current climate.

Projects utilising space technologies such as satellite navigation and imagery and the wireless transmission of data are finding new ways to help protect the health of wild animal populations around the world.

Here, we feature some of the initiatives driving positive change in the sector.

WAMCAM: Monitoring Endangered Species Through AI

WAMCAM: Monitoring Endangered Species Through AI

The WAMCAM project was originally created to aid researchers studying the native leopard population in Borneo. The process of setting up and checking live animal traps and camera traps in the dense jungle was a long-winded process that didn’t allow for wide scale study.

The solution was the WAMCAM, a battery-powered camera with added AI capabilities to identify the species of animals captured by traps. When an animal triggers a trap, the camera, which is connected to remote devices via satellite, will send a signal to researchers. This allows researchers to only travel through the rainforest when needed and makes tagging and health monitoring more efficient.

Satellite navigation technology can also be used in areas with decreased visibility to locate traps across a wider area for more extensive studies on animal population.

All the information gathered is stored digitally, resulting in clearer, more reliable research data to be shared globally.

Space Applications for Wildlife

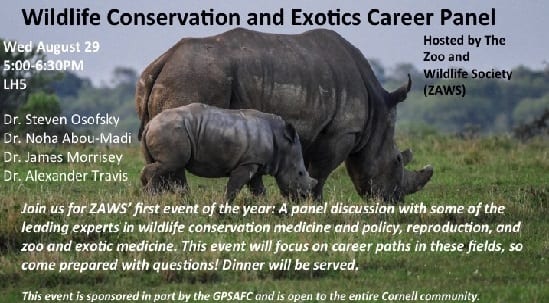

This project provides a global service for the monitoring of wildlife habitats and nature around the world. Designed for governments, NGOs, businesses and universities, the project delivers regular wildlife trend reports, wildlife management advice and crisis prevention plans.

The project uses existing data collected by satellites monitoring the earth to provide reports on habitat quality around the world. By comparing historical data from the satellites to current satellite imagery, trends and changes can be detected and plans put in place for the protection of natural habitats.

Light pollution, land ecosystems, marine ecosystems and the quality of animal habitats can all be tracked by this innovative technology. One of the main benefits of this, is that it can be used in any location.

SISMA: Monitoring Domestic and Wild Herds

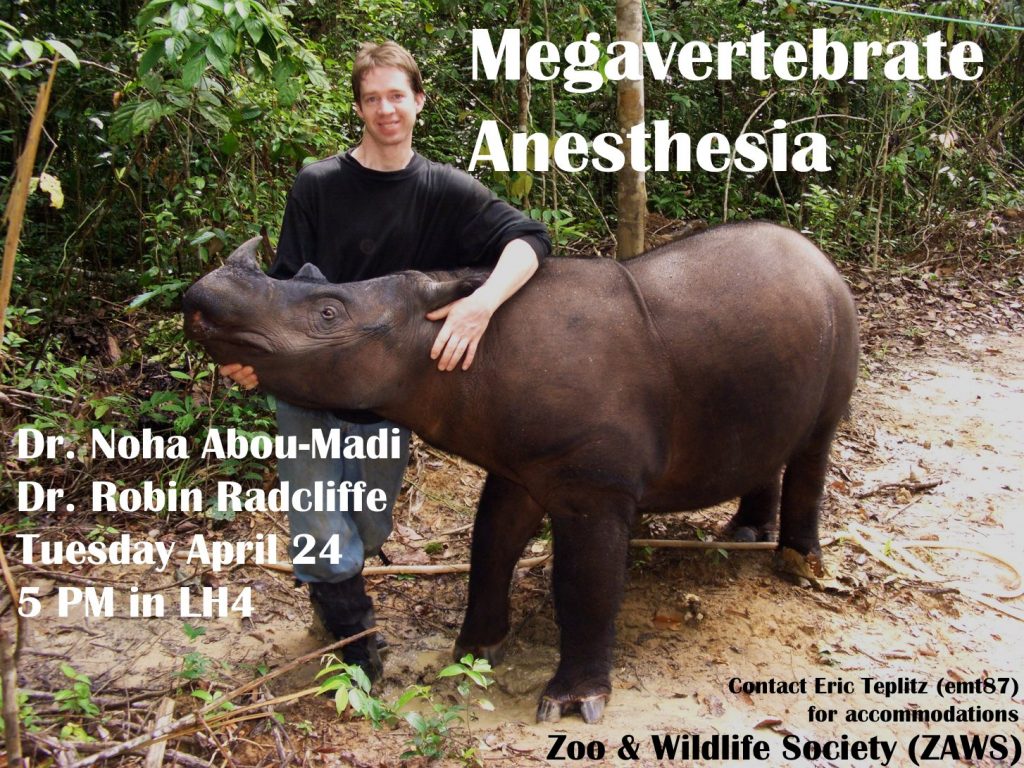

The SISMA project has been created with herders and agricultural state agencies in mind. One element of this project works to protect the reindeer population in Russia. Due to weak terrestrial communications in Northern Russia, the scheme utilises satellite navigations systems, Earth Observation and satellite imagery to track herds. This technology has the aim of reducing animal loss, preventing disease and managing habitats through remote, accurate monitoring.

The project includes a collar system connected to a mobile app to inform herders of their animals’ location and check for disease via temperature monitoring and alerts.

There is also a ‘disease channel’ for veterinarians to share early warning signs for diseases. The final element is the ‘data centre’ which collects current and historical statistics for further analysis, accessible via cloud services.

Funding Conservation Projects

Finding new, sustainable ways to protect endangered species and monitor the health of wild animals around the world is crucial.

For projects such as these to become more wildly accessible, they need support and funding from governments, local authorities and commercial stakeholders.

These projects have all received essential funding from ESA Business Apps.

ABOUT THE ORGANIZATION:

The European Space Agency (ESA) is an international organisation which organizes European space programs to find out more about the Earth, our solar system and the Universe. ESA is dedicated to encouraging investment in space research and satellite-based technologies and services for the benefit of Europe and the rest of the world.

The European Space Agency: Business Applications (ESA-BA) offers zero-equity funding, access to their network and project management advice to any business looking to use space technologies for new services.

To discover more projects they’ve helped grow, head over to the ESA-BA funding page.