“When it comes to student learning and achievement, the physical environment is a full partner.” – Dr. Lorraine Maxwell, Cornell University

Another annual NYSIPM Conference is in the books and it was certainly different from what we imagined when we started planning last year. Covid-19 caused us to move the in-person gathering from April to a virtual conference in August. (Silver lining: it turns out virtual conferences are easier to get online than those we record with a video camera. You can now view the conference presentations from our YouTube channel.) The virus also both supported and distracted from our main goal of discussing school pest issues that need community interventions to address.

As I discussed in my July post, Back to School – Humans Only!, Covid-19 is an excellent example of an issue that cannot be handled by school personnel alone. We have all been called to support the openings of schools through practicing social distancing, wearing masks, and handwashing whenever we leave our homes. As we looked at pest issues with similar community connections, examples included pests like bed bugs coming into schools on backpacks, but also wheelchairs and cockroaches coming in supplies and food packaging. Increasing communication and engaging collaborators that can help address these issues in the community preventing the introduction of pests into schools were brought up repeatedly. You can view that discussion here. Drs. Dina Fonseca and Paul Curtis also provided us with excellent examples of community members working together to manage mosquitoes and deer.

Besides influencing our conference, how else will Covid-19 impact schools from an IPM perspective? A few virus mitigation practices have direct impact on pests.

Reduced clutter

To decrease items that need to be regularly cleaned and sanitized, only required items are being kept in classrooms. The elimination of furniture and cushions, fewer books, less arts and crafts materials (or materials stored in easy to clean containers) will provide less space for pests to hide. We touched on this in the blog post, Bed Bugs in Schools – Prevention. And, as we learned in our keynote address, Healthy Environments for Learning by Dr. Lorraine Maxwell, too much clutter can also lead to cognitive fatigue. While there is much influencing learning outcomes this year, we can hope that simplifying classrooms will help reduce pests and support learning.

Food in the classroom

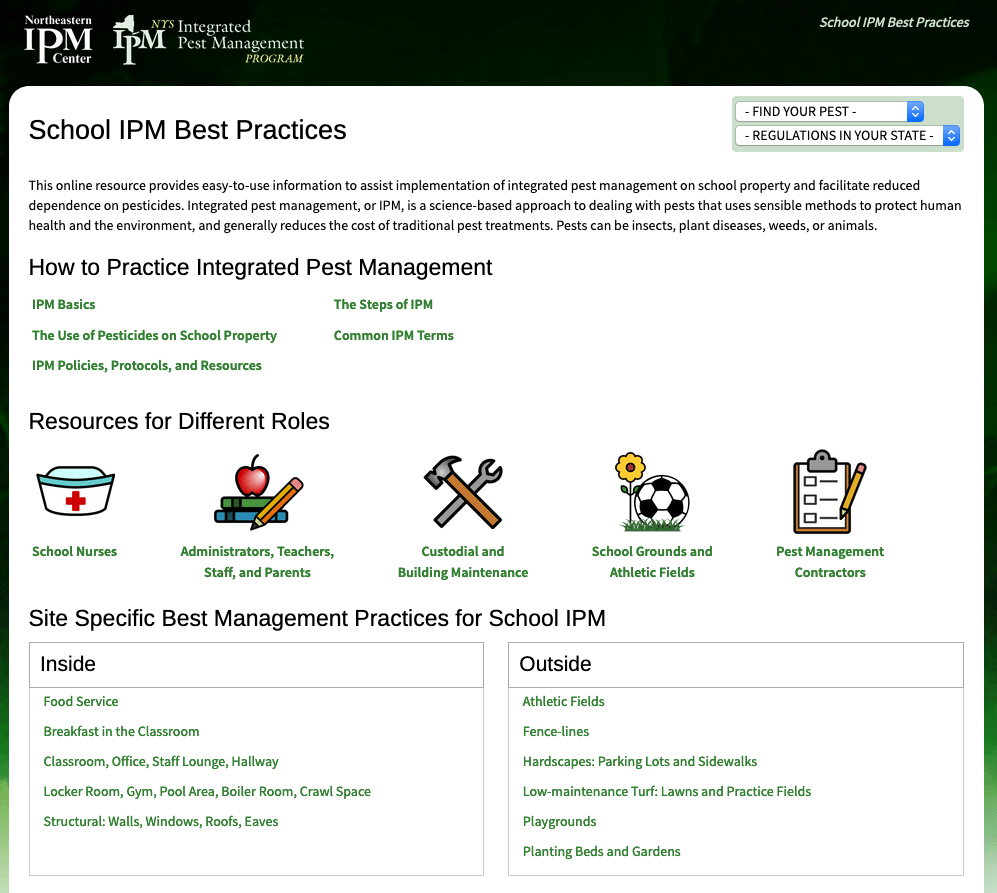

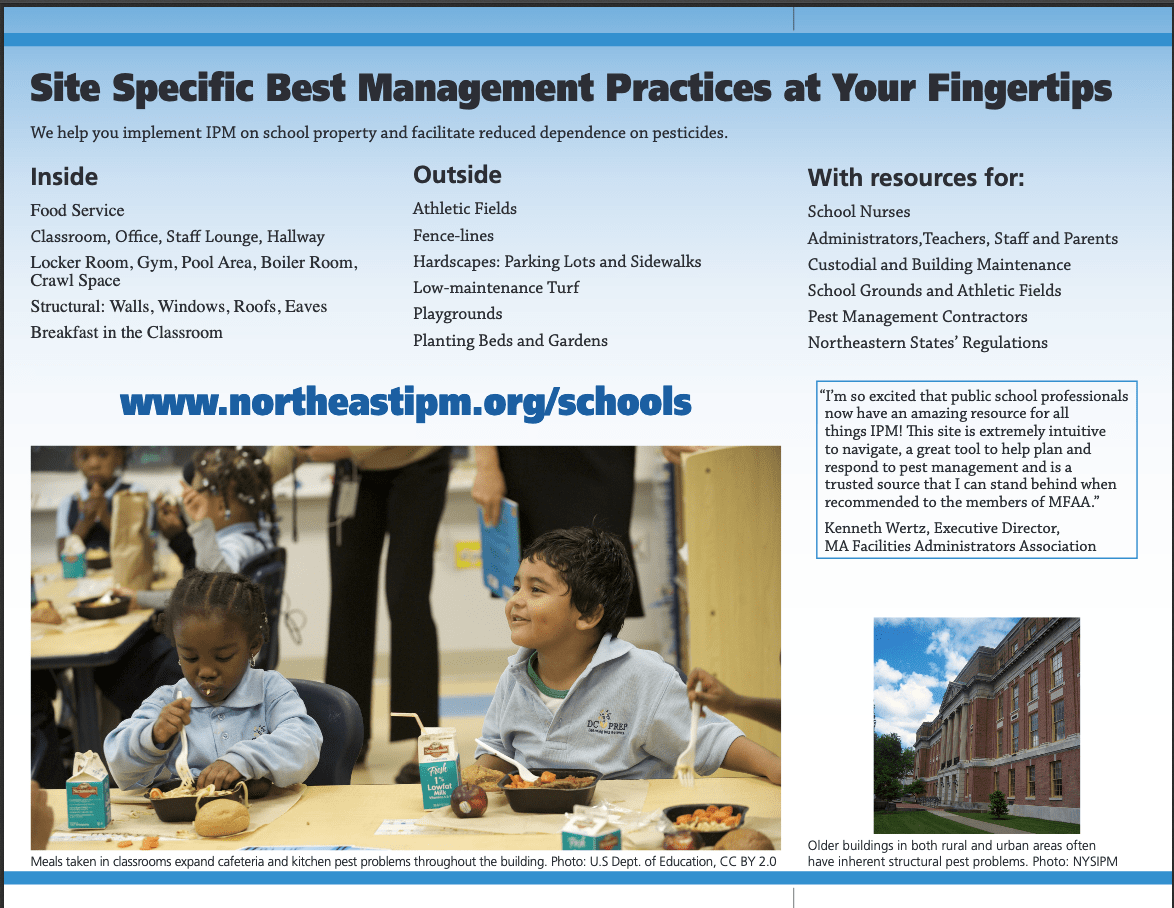

There will be expanded food in classrooms as student travel within building is curtailed. Breakfast in the classroom has already proven to be challenging. This year lunch in the classroom, as well as teacher breaks, will increase the volume of food and food waste, the number of spills, and the amount of cleaning occurring throughout the school. On the School IPM Best Practices website, you can find information and resources on breakfast in the classroom.

Ventilation

To increase ventilation, windows and doors are being encouraged to be left open. Open doors leave opportunities for rodents and flying insects to enter buildings. Windows should have screens in place to exclude pests, but have screens been checked for holes or bent frames? Bobby Corrigan discussed rodent exclusion in his presentation, Identifying and Understanding the Rodent Vulnerable Areas (RVAs) of Schools: Essential for Sustainable IPM.

Sanitation

With IPM, we usually discuss cleaning more than sanitation, but Covid-19 has created a shift. (Note: this is unfortunate as this particular virus succumbs to soap and water.) We are not the experts on this issue, but have included a couple of blog posts to help provide some guidance:

- AIR QUALITY: Pest Management, when pests are too small to see

- Pesticide Use Guidance During COVID-19

The most important outcome of the conference is the message that school building matters and, indeed, as Dr. Maxwell concludes, “When it comes to student learning and achievement, the physical environment is a full partner.” And we all have a part to play.

Be sure to visit our School IPM 2020: Where We’ve Been and What’s Next webpage for information on our speakers and links to the recordings of all the presentations.

For more information on school IPM, visit our Schools and Daycare Centers webpage.