Year in and out, outreach to schools has our community IPM staff going back to school. Literally. We work with maintenance staff, nurses, groundskeepers, teachers, and parents. We provide the insight and know-how it takes to keep kids safe from pests and pesticides both. But schools are tricky to manage because—well, think of them as a village. You’ve got your cafeterias, laboratories, auditoriums, theaters, classrooms, athletic fields, playgrounds. Add in vacation and after-hours use for public meetings, community sports teams, summer schools and camps. Plus, New York’s laws restrict when, where and how pesticides can be used at school.

Which means you’ve got work. Because chances are, you’ve got pests.

- Two years. Yup. Ticks know how to make good use of their time.

- Get yourself some super-pointy tweezers, the type that airport security would probably confiscate. Be firm: steady and straight up until that sucker lets go.

- Named for the white dot on the female’s back, this tick has a few tricks up its sleeve. More to come in another post.

Worried about ticks? By rights you should be. The hazards can hardly be overstated. We help teachers, school nurses, and entire communities learn how to stay tick-free regardless the season—and warn them that old-time remedies could increase the likelihood of disease.

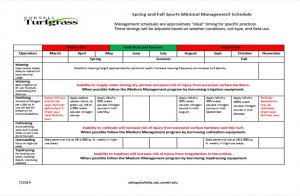

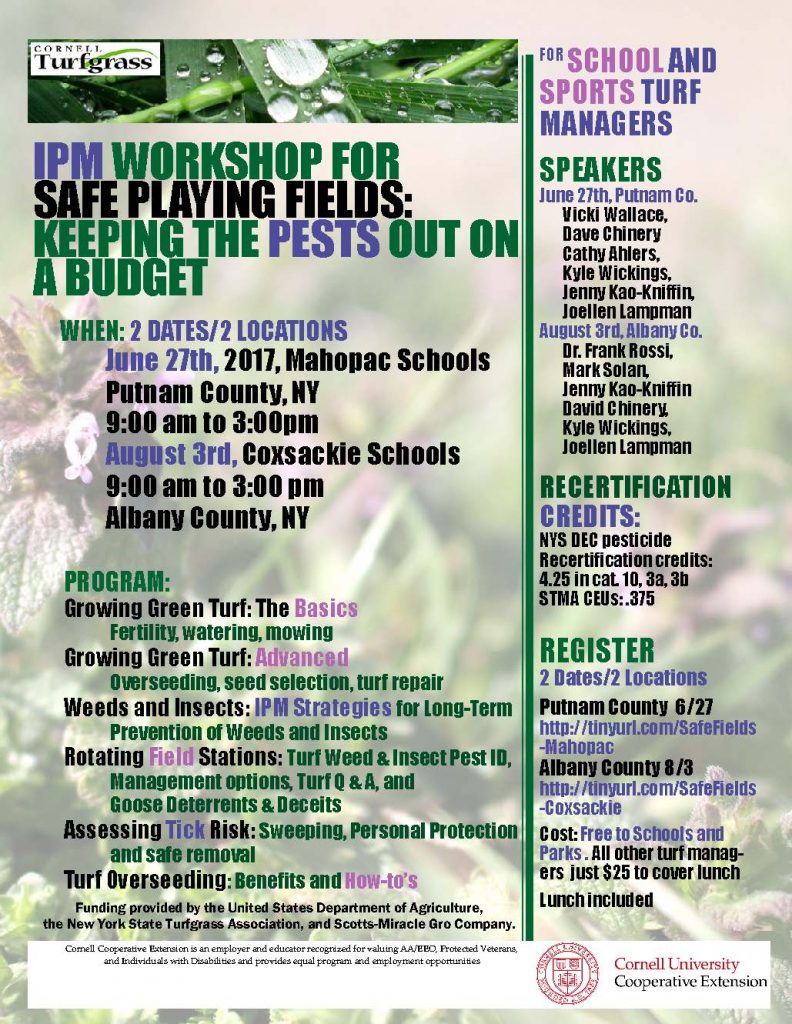

Next up—unsafe playing fields. Is there goose poo on athletic fields and playgrounds? It’s not just unsanitary—it makes for slick footing and falls. And take it from us: weedy, compacted soil is a “slick footing and falls” risk too. How to manage turf, pesticide-free? We teach repetitive overseeding as a thoughtful alternative to repetitive herbicides. We’ll get to that in another post.

And then you’ve got your ants, bed bugs, cockroaches, drain flies, drugstore beetles, fleas, grubs, lice, mice, mosquitoes, pigeons, rats, termites and wasps. Did we say we get calls? Each year we field several hundred. Then, of course, there’s the workshops we lead, the conferences we speak at, the media interviews we give. Work, yes, but also deeply rewarding.