By Meredith Swett Walker. Originally published on Entomology Today, by the Entomological Society of America, November 2017. Republished with permission.

Tick specimens embedded in Lucite can help school nurses distinguish disease carrying ticks like Ixodes scapularis from other species. Nurses are also provided with a tick removal tool with a web address directing them to online IPM resources for schools. (Photo credit: Kathy Murray, Ph.D.)

School nurses do more than just apply bandages to scraped knees and administer asthma inhalers. They are also health educators, they help control communicable diseases, and they even do some pest management.

Meredith Swett Walker

In the past, the dreaded head louse (Pediculus humanus capitis) was likely the only pest a school nurse needed to worry about. But, with the rise of arthropod-borne diseases like Lyme disease, West Nile, and Zika, nurses increasingly find themselves thinking about tick and mosquito control as well. Bed bugs, meanwhile, are also cause for concern, and as head lice evolve resistance to traditional insecticidal treatments, even these pests require more sophisticated control methods. But school nurses typically haven’t received training in pest ecology or integrated pest management (IPM.)

At Entomology 2017 in Denver, Kathy Murray, Ph.D., of the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry presented her work with the Northeast School Integrated Pest Management Working Group to engage school nurses in IPM for public health pests in schools. This project aims to give school nurses the tools, resources, and training that they need to promote and support IPM policies in schools. The work was endorsed by the National School Nurse Association and supported by the Northeastern IPM Center.

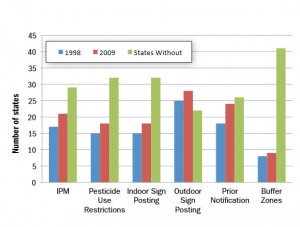

In the last 15 years, many states have started requiring schools to practice IPM. This may seem odd, but a school campus is essentially a large public property, and any property, be it a building or open space, has pests. Usually, IPM efforts in schools focus on facility managers or custodians. But school nurses deal directly with the effects of these pests on students and can be an important addition to the IPM team.

In many public schools, resources are spread thin. Facility managers may not always have the budget for the labor or materials necessary for effective IPM. But when facility managers and nurses come together to ask administrators or school boards for more resources for IPM, their requests have more heft, says Murray.

The Northeast School Integrated Pest Management Working Group has presented its project to engage nurses in IPM at nursing conferences. (Photo credit: Kathy Murray, Ph.D.)

In the Northeast, ticks are a major concern, particularly Ixodes scapularis (also known as the blacklegged tick or the deer tick), which transmits Lyme disease. Students may come in with ticks they picked up at home or can even pick up ticks on the school grounds. The project supplies school nurses with a tick removal tool, as well as actual ticks embedded in Lucite to aid in distinguishing disease-carrying species from non-vectors. When nurses learn more about tick ecology, they can help identify potential tick habitat on campus and work with facility managers to get it removed.

Mosquito bites themselves are not a major concern for school nurses, but arboviruses like Zika or West Nile are. When nurses know more about the behavior and ecology of mosquitoes, they can help identify mosquito breeding sites on campus, such as small pockets of standing water, and work with facility managers to address them. Where arboviruses are a serious concern, nurses may advocate for outdoor sporting events to be scheduled to avoid peak mosquito activity periods like dusk.

Murray found one health-pest relationship that many nurses were unaware of: the connection between cockroaches, mice, and asthma. The fecal material and urine of these pests are potent asthma triggers. Unfortunately, schools are a prime habitat for mice and roaches. There is food present in the cafeteria and often the classroom. In addition, school buildings are typically unoccupied at night, when mice and roaches are most active. Some research has even shown higher levels of pest-related allergens in school buildings than in the average student’s home. If nurses are concerned about asthma attacks at school, managing pests may help.

In her presentation at the Entomological Society of America’s 2017 annual meeting, Murray made the case that school nurses are often at the front lines of pest-related public health challenges. They can also be essential bridges to the wider community. When confronted with a pest problem, “nurses would like to have some solid, research-based, concise information—in multiple languages” that they can share with students’ families. The IPM project is working to provide that. While some school nurses may have never envisioned IPM as part of their job description, Murray says she has found the school nurses she works with to be interested in IPM and “very passionate about protecting student’s health.”

Read More

- NYS IPM Program: Schools and Daycare Centers IPM

- Northeastern IPM Center: Integrated Pest Management Resources for Schools

Meredith Swett Walker is a former avian endocrinologist who now studies the development and behavior of two juvenile humans in the high desert of western Colorado. When she is not handling her research subjects, she writes about science and nature. You can read her work on her blogs Pica Hudsonia and The Citizen Biologist or follow her on Twitter at @mswettwalker.