Recently members of the NYS IPM Program met in Albany as part of a joint meeting of the Clean, Green, and Healthy Schools Steering Committee and the Statewide School IPM Committee.

NYS IPM Educator Joellen Lampman demonstrates ‘dragging for ticks’ as a method to determine tick presence on school grounds.

Clean, Green, and Health Schools is coordinated by the NYS Department of Health and helmed by Dr. Michele Herdt. Their purpose is to promote a healthy learning and working environment in our state’s schools, both public and private.

From their page at health.ny.gov:

What is a School Environmental Health Program?

School environmental health is the way the physical environment of school buildings and school grounds influence the overall health and safety of occupants. School environments can impact occupant health, absenteeism, employee/student retention and satisfaction, academic performance, and operation costs for the school. Children are more vulnerable to environmental exposures because they eat and drink more, relative to their body weight, than adults, their body systems are still developing, and their behaviors put them at greater risk, such as hand-to-mouth action and playing on the ground.

Unfortunately, gaps in outside doors are a common problem in public buildings and offers easy access to rodents.

The New York State Clean, Green, and Healthy Schools Program is designed to help all school employees, volunteers, students, parents, and guardians contribute to improving their school’s environmental health. The program has been developed by a multi-disciplinary Steering Committee to help schools improve their environmental health through voluntary guidelines. Schools that participate in this program gain the opportunity and knowledge to create schools with better environmental health. The program provides information for all school occupants on policies, best practices, tools, knowledge, and resources in nine main areas:

- Indoor Air Quality;

- Energy and Resource Conservation;

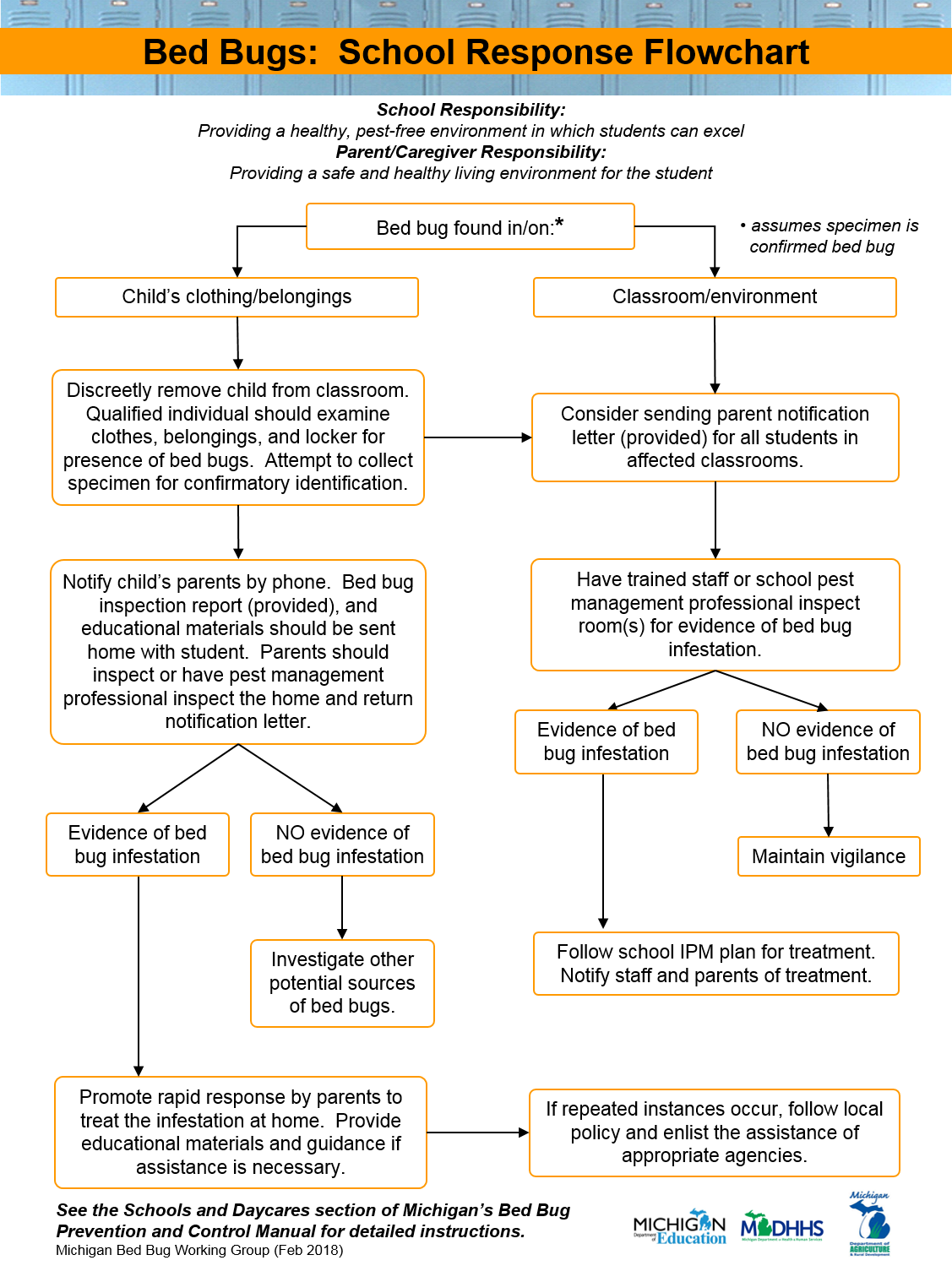

- Integrated Pest Management;

- Mold and Moisture;

- Chemical and Environmental Hazards;

- Cleaning and Maintenance;

- Transportation;

- Construction/Renovation;

- Water Quality.

Last year, they began a free pilot program to create safer and healthier learning and working environments for all students and staff across New York State. We are looking for schools that would like to be a part of this pilot program and improve the environmental health of their school through low or no cost actions.

As of October, 2018 they have ten school buildings involved, and hope to have at least 10% of NY schools enrolled in the program by 2024.

The NYS IPM Program is glad to be part of the efforts.

Later in the morning Vickie A. Smith and David Frank from the NYS Dept. Of Education shared their work with charter schools, engaging the participants in the joint meeting with ideas on how to better reach this growing segment of education in NYS.

While we have sought to find a way to work with non-public schools in NY, charter schools are also another subset with their own particular concerns. Like many non-publics, some charter schools operate in rented buildings (some are indeed buildings owned by a public school), and therefore it is not always clear who is responsible for environmental issues school staff face. Charter schools have multiple authorities to report to depending on their location: The NYS Board of Regents, SUNY trustees, NY City Department of Education and the Buffalo City School District. Many students in charter schools are ‘at-risk’. 80% are considered economically challenged, or have disabilities or language barriers.

Charter schools are considered public schools and must comply with many of the same rules. Our day of discussion proved there are plenty of opportunities to increase the use of IPM in all schools in NY State.

Best Management Practices website hosted by the Northeast IPM Center

Staff of the NYS IPM Program finished out the day’s meeting with a look at Don’t Get Ticked NY efforts. This included sharing the Ticks on School Grounds posters.

More information on our work with schools

For more on ticks visit our page Don’t Get Ticked New York.

Download this poster and others on reducing the risk of ticks