It’s spring fever. That is what the name of it is. And when you’ve got it, you want — oh, you don’t quite know what it is you do want, but it just fairly makes your heart ache, you want it so! ~Mark Twain

Part of what we want is to be outside! And, with COVID-19, more people than ever are heading to the great outdoors. Which, unfortunately, is where the ticks are. And ticks want a blood meal. In the early spring we still have some adult blacklegged tick adults hanging around. But the time has also come again for blacklegged tick nymphs to look for a meal. As well as American dog ticks. And lone star ticks. And the recently discovered Asian longhorned tick.

And people want answers to questions such as this one, “I just removed a tick from my child. What should I do now?”

We’ll start by stressing there are steps you can take to reduce the likelihood of a tick bite. This has been covered in multiple places including our Don’t Get Ticked NY website and various blogs including keeping dogs tick free, using repellents effectively, and the proper use of permethrin treated clothing. If you do find one attached, we covered tick removal in the blog post It’s tick season. Put away the matches and YouTube video How to remove a tick.

Identifying ticks

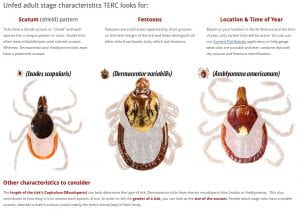

With four major tick species in New York, it’s important to identify which one bit you. Each species, life stage, and, for adults, whether it is a male versus female have different color patterns. The length of the mouthparts vary between ticks. They have festively named festoons which can also help with ID. As ticks are freakishly small, and we are looking at even smaller parts of their body, it is handy to have a magnifying lens, a good smartphone camera and a steady hand, or, better yet, a microscope. Don’t have one? There are options for having someone identify the tick for you. They include:

- Most County Cornell Cooperative Extension offices (most are closed due to COVID-19, but contact them to see if they are still conducting pest identification)

- Cornell University Insect Diagnostic Laboratory (currently on hold due to COVID-19)

- Tick Identification at TickEncounter Resource Center

- The Tick App – a citizen science project with a free smartphone app collecting information on how and where people are becoming exposed to ticks

If you want to give identification a go, the TickEncounter Resource Center has an excellent guide highlighting the scutum, festoons, and life history. Life history? Yes! Life history should only be used as a clue, however. Ticks don’t read the books and every life stage of the blacklegged tick has been found throughout the year.

Tick-borne pathogens

Identification matters because different tick species can transmit different tick-borne pathogens. Which is information you want to give your health care provider to help them make an informed decision..

First, let’s be clear that we provide mostly information about ticks. Any information about tick-borne pathogens that cause disease is restricted to what pathogens are carried by what tick species and how they are transmitted. It is beyond the scope of our roles as IPM Educators to discuss diagnosis, symptoms, and treatment. (For this information, we refer you to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Tickborne Diseases of the United States page.)

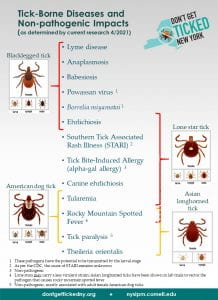

The poster to the right shows what disease pathogens can be transmitted by the three ticks of greatest human concern in NY, the blacklegged tick, dog tick, and lone star tick. To date, no Asian longhorned ticks in the U.S. have tested positive for any tick-borne pathogens.

What’s the risk?

A question you will likely be asked when reporting a tick is, “How long was the tick attached?”. In my honest opinion, this is a rather silly question. Ticks are very, very good at not being noticed. They want to stick around for up to a week feeding. To help deter detection, they release antihistamines and painkillers in their saliva. And, perhaps more importantly, none of us want to admit to ourselves that a tick was feeding on our blood for days. It’s a hard psychological pill to swallow. There is also some question in the medical literature about the time required for transmission of the bacteria that causes Lyme disease. Especially if the tick was removed improperly. And we know Powassan virus can be transmitted in a matter of minutes. But the question will still likely be asked.

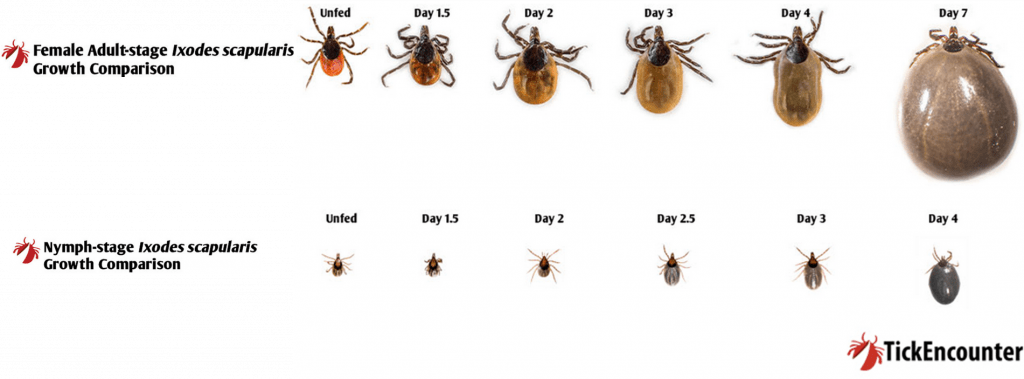

The answer? Take another look at that tick and refer to TickEncounter who has helpfully created charts showing the growth of ticks as they feed.

I have found this chart particularly useful when people swear the tick was on them for only a few hours. Having an estimate of the attached time is helpful information for your physician.

And now back to the original request: “I just removed a tick from my child. What should I do now?” In this case, we were able to put the tick under a microscope to help with identification. Before reading on, what would you say it is?

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

This looks like a blacklegged tick nymph which was attached for 1 to 2 days, so any pathogens carried by the tick might have been transmitted. I recommended printing the Tick-Borne Diseases and Non-Pathogenic Impacts sheet, circling the identified species and life stage, writing down the estimated time of attachment, and calling their health care professional.

One last question often asked – “Should I get the tick tested?”

We follow the CDC recommendation of not having the tick tested for diagnostic purposes. The reasons include:

- Positive results showing that the tick contains a disease-causing organism do not necessarily mean that you have been infected.

- Negative results can lead to false assurance. You may have been unknowingly bitten by a different tick that was infected.

- If you have been infected, you will probably develop symptoms before results of the tick test are available. If you do become ill, you should not wait for tick testing results before beginning appropriate treatment.

Having said that, you can contribute to a community-engaged tick surveillance project investigating the impact of climate change on the emergence of ticks and tick-borne diseases in New York.

Promoting IPM, including monitoring and personal protection, as best management practices for avoiding ticks and tick-borne disease.And finally…

If you don’t get bitten by a tick, you don’t need to go through this process. Our Don’t Get Ticked NY campaign provides you with the information you need to protect yourself from the risk of tick-borne diseases. Check it out before your next trip outdoors.

Let’s stay safe out there as we enjoy the beautiful spring.