… and now, more than ever, poison ivy’s gonna make you itch. (The Rolling Stones)

I remember the first time I had poison ivy. The particulars are long lost along memory lane. Even so, it was unforgettable. Most likely I was about five years old and, as a born and bred tomboy, I’d been scrambling around in the woods. From that point forward I knew exactly what poison ivy looked like. Sometimes it’s shrubby or low to the ground. Other times its hairy, ropelike vines, thicker than my wrists, twine their way up trees like ropes on the masts of tall sailing ships of yore—or so I imagine them. And yes, the vines are poisonous too.

Only once since have I gotten poison ivy—not a bad case, either. I was, after all, dressed for the occasion. I was hunting it down, one tangled root after the next, from the woods behind a friend’s daycare home. Toddlers, as we all can appreciate, are simply too young to learn the perils of poison ivy. I hauled it out of there by the bushelful. Funny that after all these years I’ve no clue what I did with it.

Burn it I did not, that’s for sure. I have the merest sketch of a memory—my mom telling me how she’d breathed the smoke from a burning heap of the stuff. Nasty. Can make you really (really) sick—a serious occupational hazard of forest-firefighters.

But these days poison ivy isn’t just a hassle for woodsy sorts who live well past the edges of nearby villages and towns. It’s getting worse for everyone, though some more than others. Why? Let’s fast-forward to the here and now. To a relative here-and-now; the research I’m citing was published in 2006 in PNAS (the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences). Research that, btw, has yet to lose its gloss. News stories as recent as 2015 (The New York Times) cite that study in noting the likely consequences of an inadvertent brush with the stuff—especially if you live in a big city. Sure, urban dwellers always had to cope with this wicked vine too. But now they have lots more to worry about than country folk do.

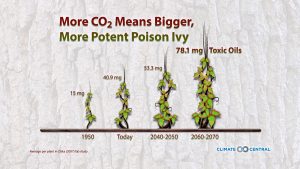

Why? Lewis Ziska, one of the lead scientists on the six-year study in a forest at Duke University, found that with increased atmospheric CO2 we get bigger, stronger, leafier poison ivy. Poison ivy that can be way more potent in large cities. Here’s how it works:

Mega-cities are proxies for the planet. They have as much carbon dioxide in their air as the rest of the planet will have in 50 years or so. And CO2 is plant food. Like so many other plants, especially weeds (more on that some other day), poison ivy responds by piling on the pounds, as it were—and producing more urushiol.

Haven’t heard of urushiol? It’s the toxic oil that causes that nasty rash. Ziska confirmed those findings in a follow-up study in growth chambers. His calculations, he told Climate Central, are based on the CO2 levels at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Research Administration (aka NOAA) Mauna Loa research station in Hawaii. What did the research tell him? CO2 concentrations on the ground, where poison ivy actually grows, are usually about 10 percent higher than they were in 1950—not long before my first encounter with poison ivy. And in urban areas they can be up to 30 percent higher.

Thirty percent. Take a moment to absorb that.

Not only that, but from parks to vacant lots, cities mimic the fragmented forests you see wherever a suburb has muscled its way into the landscape. And poison ivy likes fragmented landscapes. It also likes—well, what doesn’t it like? Poison ivy can grow in swampy forest edges and concrete rubble; along fences; in parks or on school grounds; or up and around homes and apartment buildings. So wherever you are, learn to ID poison ivy. “Leaves of three, let it be” is where you start. But some harmless plants also have clusters of three leaves. After all, the numero-uno IPM mantra for any environmental issue is prevention. And prevention is based on having a solid ID.

But surely you’re safe during winter? If only. Unlike many other weeds, which die back when the weather turns cold, the urushiol in poison ivy will get you regardless of the weather. Beware of leafless vines. This is not the time to try and yank them off your trees. If the toxin gets on your gloves or coveralls, it can get on you.

I could say so much more about no end of things related to poison ivy or rising CO2 (or both) … including (for instance) sleek vs. long-haired dogs and cats or the food choices of goats, muskrats and deer. But I have to stop somewhere. And that somewhere? It’s here.