https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=79uqMKUoIjE&feature=youtu.be

Its creators call this a billboard. And while it has much in common with the classy, upscale billboards now peppering cities and towns around the world, this particular model is actually a sophisticated piece of equipment — built to attract mosquitoes from more than a mile away.

The goal: to intercept and kill mosquitoes — specifically Aedes aegypti and kin — that might otherwise be inclined to sup on us.

The other goal: to slow the spread of Zika.

Zika is a relatively new mosquito-vectored virus. It hopscotched through Africa and Asia starting in the late 1940s, seemingly to little effect. But circa 2013 something changed. Outbreaks in Southeast Asia and several Pacific islands — where in French Polynesia the virus was linked to the neurological disorder Guillain-Barré syndrome — had scientists sounding the alarm.

Then in 2015 came Brazil. Zika hit the big time and ballooned out of control. And along with the link to Guillain-Barré came a second: to microcephaly in the brains of newborns. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of newborns.

These links between mosquito-vectored Zika and severe neurological damage have yet to be proven, but few are in the mood to wait before taking action. Which is why two unlikely actors — NBS, a Brazilian ad agency, and billboard designers Posterscope (with offices in 34 countries) — collaborated on their Mosquito Killer Billboard.

The billboard’s job: to attract mosquitoes with lactic acid (mimics human sweat) and CO2 (mimics human breath). The collaborators are demoing two of these billboards (the only two in existence) in Rio de Janeiro. Which means the jury is out on will they work on the scale they need to.

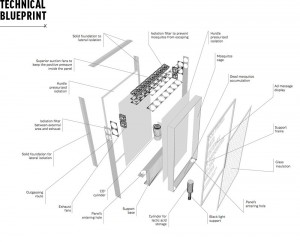

But the billboard’s Creative Commons license provides a blueprint that allows anyone, anywhere to replicate the work the designers put into their prototype.

“The idea might be a bust if simply attracts mosquitoes to places where people also congregate,” says Jody Gangloff-Kaufmann, an entomologist and Extension specialist with Cornell University’s Integrated Pest Management Program (NYS IPM). But strategically located on the periphery of public spaces, she suggests, “they could act as a sink that really does cut back on these unwanted visitors.”

Does this even matter to people in the Northeast? Rest assured. Aedes albopictus, aka Asian tiger mosquito, can also transmit Zika. This globe-trotting mosquito made landfall in the U.S. in 1985 and has spread widely through the Southeast, arriving in Long Island, the metro New York area New Jersey, Connecticut, and Rhode Island roughly ten years ago. Under laboratory conditions it vectors an impressive suite of diseases, though only a handful affect humans.

Still, that handful could prove worrisome if the tiger mosquito proves as competent a vector as its cousin A. aegypti. One factor in our favor is this: tiger mosquitoes like supping on birds even more than on us, which should lower their vector potential. But while both species are well adapted to urban lifestyles, A. aegypti prefers warmer zones in the southern U.S. For Zika, this makes A. albopictus the most likely vector of choice for people in more northerly areas.

Right now the best advice is to learn everything you can about Asian tiger mosquitoes and stay informed. Check the CDC’s website often and follow recommendations for keeping yourself, your loved ones, and your community safe.