By Linda Gayton, Highland Mills Master Gardener Volunteer

This article appeared in the August 2021 Issue of Gardening in Orange County.

When it comes to invasive species, patience and persistence are key. This is a marathon not a sprint. Eradicating invasive species takes the determination of the tortoise, not the hare. We need to exercise a consistently forward, strategic plan to manage our alien invaders. A fast sprint to the win is not usually possible.

invasive species – a non-native species to the ecosystem that they occupy, AND who’s existence causes harm to the economy, the environment, or human health.

Invasive plants grow quickly, and spread to the point of disrupting communities and ecosystems. For the most part, these invaders are not affected by native pests and diseases. The only predator they will encounter in our landscape is you.

Why should we care about invasive plant species?

Invasive plants degrade native habitat. They are poor food producers for our native wildlife. They clog waterways, destroys native habitats, ruins views, and causes wildfires. Millions of dollars a year are spent on control methods.

What are the benefits of managing invasive species?

Managing invasive species benefits wildlife, the environment, and ourselves. Our goal is to create resilience in our ecosystem. By restoring areas dominated by invasive species and helping native plant communities to thrive we can help allow biodiversity to persist and help keep natural areas intact.help allow biodiversity to persist and help keep natural areas intact.

Integrated Pest Management

To begin to eradicate invasive species, we must first develop an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) plan. IPM is a process we use to solve pest problems while minimizing risk to people, wildlife, and the environment.

There are 6 steps to an IPM strategy:

-

- Sample for Pests (Inspect and Monitor): Is there a real problem?

- Properly identify pests: Is it really the pest you think it is?

- Learn the pest biology: Will it be a long-tern problem, or will it be gone next week?

- Determine an action threshold: Do you need to act?

- Choose Tactics: What’s the best treatment?

- Evaluate: How did it work?

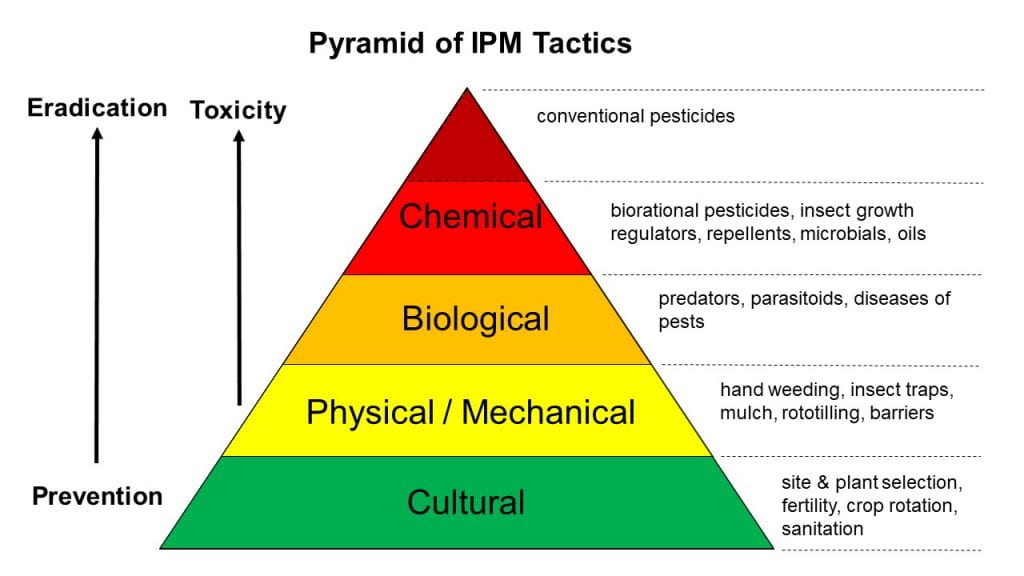

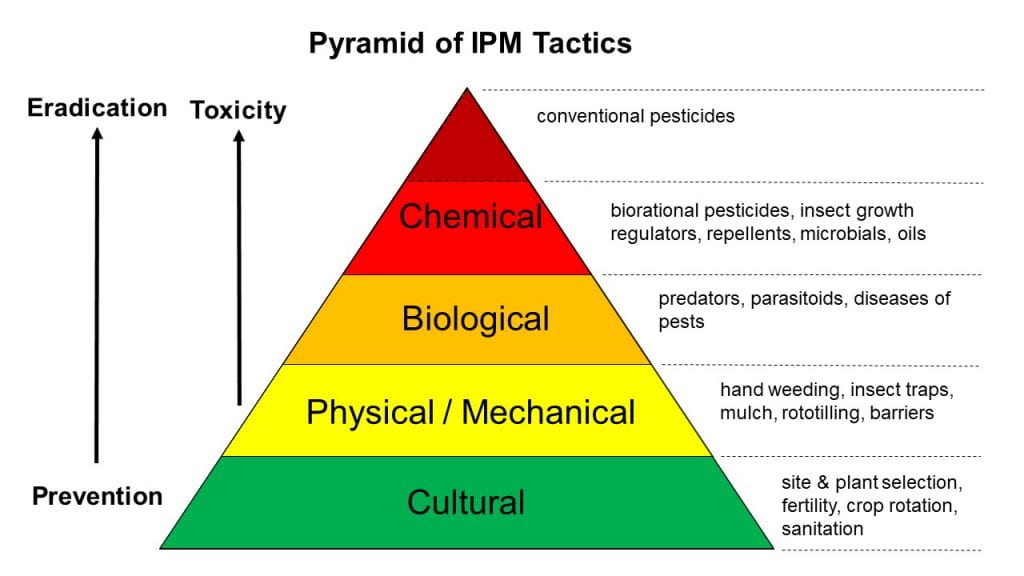

When it comes to control tactics in IPM, we start with the least toxic when available and move up the pyramid to the most toxic (conventional pesticides) as needed.

Here are some IPM Strategies to implement when dealing with what I consider three of our top plant invaders:

-

- Common Reed / Phragmites (Phragmites australis)

- Japanese Knotweed (Fallopia japonica)

- Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora)

For each of these formidable opponent, we head right to the mechanical/physical control methods followed by strategic application of chemical herbicides.

Some of the following strategies include herbicide recommendations. Every effort has been made to provide correct, complete, and up-to-date herbicide recommendations. Nevertheless, changes in herbicide regulations occur constantly and human errors are still possible. These recommendations are not a substitute for herbicide labeling. Please read the label before applying any herbicide. The label is the law!

Some of the following strategies include herbicide recommendations. Every effort has been made to provide correct, complete, and up-to-date herbicide recommendations. Nevertheless, changes in herbicide regulations occur constantly and human errors are still possible. These recommendations are not a substitute for herbicide labeling. Please read the label before applying any herbicide. The label is the law!

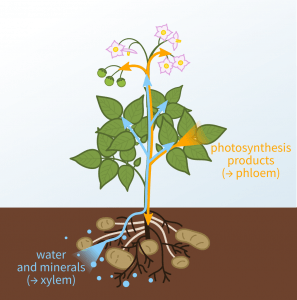

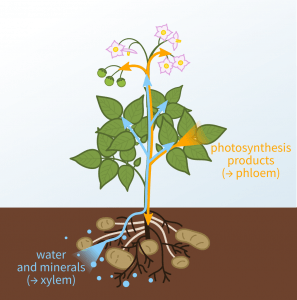

If you decide to use an herbicide to combat these invaders, timing is key. When applied to a plant, the herbicide glyphosate, one of the most widely used weed killers, will be translocated in the plant’s phloem, which the plant uses to transport sugars and other metabolic products. But the herbicide will only be transported in the direction the plant is moving sugars. For the majority of the season plants are using sugars that they had stored in the rhizomes to grow, meaning that sugars are moving upwards in the plant’s phloem. Only once a plant starts to flower does it begin to store sugars back down in the rhizomes, meaning that sugars are moving downward in the plant and when applied glyphosate will reach the rhizomes. Both Phragmites and Japanese knotweed have extensive rhizomes

If you decide to use an herbicide to combat these invaders, timing is key. When applied to a plant, the herbicide glyphosate, one of the most widely used weed killers, will be translocated in the plant’s phloem, which the plant uses to transport sugars and other metabolic products. But the herbicide will only be transported in the direction the plant is moving sugars. For the majority of the season plants are using sugars that they had stored in the rhizomes to grow, meaning that sugars are moving upwards in the plant’s phloem. Only once a plant starts to flower does it begin to store sugars back down in the rhizomes, meaning that sugars are moving downward in the plant and when applied glyphosate will reach the rhizomes. Both Phragmites and Japanese knotweed have extensive rhizomes

Carefully disposing of plant material from invasive plants is extremely important as many invasive species can grow from small fragments. Two common practices are burning plant material (according to state and local laws) and putting it in black garbage bags and sending it to the landfill. To reduce the volume before shipping it off to the landfill, you can leave it on an extremely hot surface such as an asphalt driveway prior to being discarded. You should not try and compost this material as it will most likely resprout and cause more problems.

Common Reed / Phragmites

Phragmites, also known as common reed, is a perennial grass that can grow over 15 feet tall. It is commonly found in marsh and wetland areas where it forms dense stands that crowd out native vegetation. These monoculture that do not support the diversity needed for a thriving ecosystem

Phragmites, also known as common reed, is a perennial grass that can grow over 15 feet tall. It is commonly found in marsh and wetland areas where it forms dense stands that crowd out native vegetation. These monoculture that do not support the diversity needed for a thriving ecosystem

Phragmites spreads by both rhizome and wind pollinated seed. It has very deep roots and thrives in moist areas and aquatic environments. It also conducts chemical warfare against other plants by secreting allelochemicals to suppress their growth.

For this formidable opponent, we head right to the mechanical / physical control methods followed by strategic application of chemical herbicides.

Method A: Clip and Drip

After the plant has flowered, clip and remove stem, then immediately apply the herbicide glyphosate, to the hollow stems with a drip bottle. Stems can be bundled before they are clipped to make it easier to drip herbicide on hundreds of stems simultaneously. This method is extraordinarily labor intensive but can work wonderfully without the loss of native plants. Remember to dispose of any cut material properly.

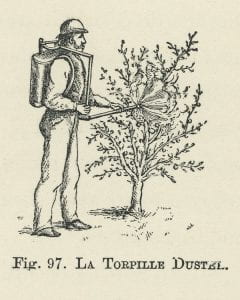

Method B: Cut and Spray

After the plant has flowered, cut and remove stem followed by targeted spraying of an appropriate herbicide via backpack mounted sprayers or mist blowers. Remember to dispose of any cut material properly.

Method C: Burn It

Conduct a controlled burn following state and local laws as well as safety guidelines. This will kill stems and seeds. If regrowth occurs use chemical methods.

Method D: Drown It

Drown it. Cut stems under 6” of water. Dispose of cut material properly. Phragmites will drown in 1 year by early fall if water level is maintained.

For each of these methods, it is important to reevaluate yearly and determine what if any further eradication is necessary. Once removing a stand of phragmites make sure you remove the layer of dead shoots, stems, and roots on top of the soil surface before a restoration planting of native plants.

Japanese Knotweed

Japanese knotweed is an herbaceous perennial that creates dense thickets that crowd and shade out native vegetation. In the United States rhizomes can reach 30-75 feet in length and are the chief cause of spread. Fragment of stem and rhizome can regenerate new plants. In big storm events pieces of the plant are broken off and transported to new areas, where they can establish new colonies. Finding small plant fragments digging them out and disposing of them properly can go a long way in saving resources, time, and the damage of future infestations.

Japanese knotweed is an herbaceous perennial that creates dense thickets that crowd and shade out native vegetation. In the United States rhizomes can reach 30-75 feet in length and are the chief cause of spread. Fragment of stem and rhizome can regenerate new plants. In big storm events pieces of the plant are broken off and transported to new areas, where they can establish new colonies. Finding small plant fragments digging them out and disposing of them properly can go a long way in saving resources, time, and the damage of future infestations.

Along waterways Japanese knotweed replaces riparian vegetation reducing diversity and altering the aquatic ecosystems. The loss of tree and shrub canopy can cause an increase in water temperature which in turn affects water chemistry and fish habitat. The loss of leaf litter and woody debris results in a loss of shelter for fish and invertebrates. The inability of ground covers and mosses to grow beneath the dense canopy of knotweed results in bare soils leaving banks susceptible to erosion resulting in siltation in stream beds, which again alters fish habitat.

We will once again skip up the pyramid and head to our mechanical/physical management tools in order to begin controlling Japanese knotweed.

Method A: Dig, Dig, Dig

Cut the knotweed stalks, digging out the root crowns and as much of the rhizome network as possible. This is very labor intensive and may take several years to gain control of a stand of Japanese knotweed.

Method B: Cut, Dig, Cover

Cut the knotweed stalks, digging out the root crowns and as much of the rhizome network as possible. Then cover the ground with thick black landscape plastic to block sunlight and thereby destroy any remaining rhizomes. Leave covered for at least one year. Experimental plots which were left covered for three years, showed less regrowth of knotweed.

Method C: Cut, Cut, Cut

Cut down knotweed plants 2 or 3 times each growing season. Dispose of properly. Several years of successive cutting will weaken the knotweed’s rhizomes, so they can be pulled out with relative ease.

Method D: Cut and Spray

Cut down knotweed plants 2 or 3 times each growing season. Dispose of properly. Several years of successive cutting will weaken the knotweed’s rhizomes, so they can be pulled out with relative ease.

Biological Control

The Knotweed Psyllid (Aphalara itadori) was released on June 10th, 2020, in New York’s Tioga and Broome counties. Research and monitoring are ongoing.

For each of these methods, it is important to reevaluate yearly and determine what if any further eradication is necessary. Once control has begun make sure to implement a restoration planting of native plants.

Multiflora Rose

Multifloral Rose is an herbaceous shrub in the rose family (Rosaceae). It has canes or stems) have numerous thorns and can grow up to 15 feet in length and usually arc toward the ground and takes root, a process called layering. This creates dense thickets 6-10 feet tall. After establishment, individuals can increase their size by 1-2 feet a week during midsummer. Multifloral rose has clusters of showy, fragrant white flowers in late May or June. It spreads through seed, root sprouting, and layering. The fruit, known as rose hips, are eaten and dispersed by our feathered friends, and can persist and remain viable in the soil for up to 20 years.

Multifloral Rose is an herbaceous shrub in the rose family (Rosaceae). It has canes or stems) have numerous thorns and can grow up to 15 feet in length and usually arc toward the ground and takes root, a process called layering. This creates dense thickets 6-10 feet tall. After establishment, individuals can increase their size by 1-2 feet a week during midsummer. Multifloral rose has clusters of showy, fragrant white flowers in late May or June. It spreads through seed, root sprouting, and layering. The fruit, known as rose hips, are eaten and dispersed by our feathered friends, and can persist and remain viable in the soil for up to 20 years.

Method A: Dig, Dig, Dig

Remove isolated individuals before they multiply. Small populations of young plants are not difficult to pull taking care to use protection against thorns. Be sure to pull the entire root system to prevent re-sprouting.

Method B: Mow, Mow, Mow

Repeated cutting or mowing at the rate of three to six times per growing season, for two to four years, has been shown to be effective in achieving high mortality.

Method C: Cut and Spray

Mow or cut large infestations to prep for herbicide application After mowing, wait for knee level regrowth before treating with herbicide. While foliar sprays can be done anytime during the growing season, all these chemicals will also harm non-target herbaceous plants and trees if applied to their leaves. Care needs be taken to prevent damage to non-target plants.

As previously stated, patience and persistence are necessary when attempting to eradicate an invasive species. In order to sustain myself through what seems like a never-ending task, I maintain the attitude that I am working with nature on a productive journey. I find also that monitoring progress and achieving even minimal success is very encouraging. When we keep in mind all the positive effects that our efforts are having on the wildlife, our ecosystem, and ourselves, the reward is great.

It is my hope that I have shared some of the tools to help you take on one or more of our invaders.

Stop the Silent Invasion!

Please spread the word, not the weeds !

Resources

General

Managing Invasive Plants: Methods of Control – University of New Hampshire Extension

Mistaken Identity? Invasive Plants and their Native Look-alikes – Delaware Department of Agriculture

New York State Invasive Species – New York Invasive Species Information – Cornell University

Common Reed / Phragmites

Common Reed – New York Invasive Species Information – Cornell Cooperative Extension

Successfully Managing Phragmites – Ecological Landscape Alliance

Japanese Knotweed

Homeowner’s Guide to Japanese Knotweed Control – Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources

Japanese Knotweed – New York Invasive Species Information – Cornell Cooperative Extension

Japanese Knotweed – University of Wisconsin Extension

Managing Japanese Knotweed: Two Small-Scale Strategies – Ecological Landscape Alliance

Multifloral Rose

Multifloral Rose – New York Invasive Species Information- Cornell Cooperative Extension

Multifloral Rose – Penn State Extension

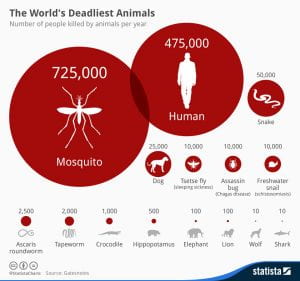

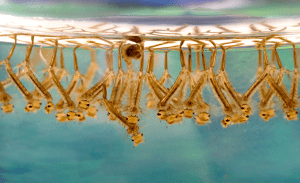

Did you know one of the smallest insects in the world also happens to be the deadliest to humans? Yup, those pesky mosquitoes renowned for ruining many an outdoor evening event kill more humans every year than sharks, snakes, lions, crocodiles, and hippos combined. Of course they don’t do it alone; mosquitoes do not actually cause diseases themselves but act as vectors (carriers) for deadly diseases such as malaria, encephalitis, dengue fever, yellow fever, West Nile virus and Zika, to name a few. To transmit these diseases, mosquitoes first need to feed on the blood of a human or other animal that is already infected by the disease. Afterwards when they bite a healthy human, they pass on the disease.

Did you know one of the smallest insects in the world also happens to be the deadliest to humans? Yup, those pesky mosquitoes renowned for ruining many an outdoor evening event kill more humans every year than sharks, snakes, lions, crocodiles, and hippos combined. Of course they don’t do it alone; mosquitoes do not actually cause diseases themselves but act as vectors (carriers) for deadly diseases such as malaria, encephalitis, dengue fever, yellow fever, West Nile virus and Zika, to name a few. To transmit these diseases, mosquitoes first need to feed on the blood of a human or other animal that is already infected by the disease. Afterwards when they bite a healthy human, they pass on the disease.

Mosquitoes are beneficial to plants as well. Many adult mosquitoes depend on plant nectar for their energy, and while retrieving the nectar, they also pollinate plants. And as we know that pollination is key to plant reproduction, mosquitoes play an important role in helping plants survive so they can provide food and shelter for other organisms.

Mosquitoes are beneficial to plants as well. Many adult mosquitoes depend on plant nectar for their energy, and while retrieving the nectar, they also pollinate plants. And as we know that pollination is key to plant reproduction, mosquitoes play an important role in helping plants survive so they can provide food and shelter for other organisms.

Some of the following strategies include herbicide recommendations. Every effort has been made to provide correct, complete, and up-to-date herbicide recommendations. Nevertheless, changes in herbicide regulations occur constantly and human errors are still possible. These recommendations are not a substitute for herbicide labeling. Please read the label before applying any herbicide. The label is the law!

Some of the following strategies include herbicide recommendations. Every effort has been made to provide correct, complete, and up-to-date herbicide recommendations. Nevertheless, changes in herbicide regulations occur constantly and human errors are still possible. These recommendations are not a substitute for herbicide labeling. Please read the label before applying any herbicide. The label is the law! If you decide to use an herbicide to combat these invaders, timing is key. When applied to a plant, the herbicide glyphosate, one of the most widely used weed killers, will be translocated in the plant’s phloem, which the plant uses to transport sugars and other metabolic products. But the herbicide will only be transported in the direction the plant is moving sugars. For the majority of the season plants are using sugars that they had stored in the rhizomes to grow, meaning that sugars are moving upwards in the plant’s phloem. Only once a plant starts to flower does it begin to store sugars back down in the rhizomes, meaning that sugars are moving downward in the plant and when applied glyphosate will reach the rhizomes. Both Phragmites and Japanese knotweed have extensive rhizomes

If you decide to use an herbicide to combat these invaders, timing is key. When applied to a plant, the herbicide glyphosate, one of the most widely used weed killers, will be translocated in the plant’s phloem, which the plant uses to transport sugars and other metabolic products. But the herbicide will only be transported in the direction the plant is moving sugars. For the majority of the season plants are using sugars that they had stored in the rhizomes to grow, meaning that sugars are moving upwards in the plant’s phloem. Only once a plant starts to flower does it begin to store sugars back down in the rhizomes, meaning that sugars are moving downward in the plant and when applied glyphosate will reach the rhizomes. Both Phragmites and Japanese knotweed have extensive rhizomes Phragmites, also known as common reed, is a perennial grass that can grow over 15 feet tall. It is commonly found in marsh and wetland areas where it forms dense stands that crowd out native vegetation. These monoculture that do not support the diversity needed for a thriving ecosystem

Phragmites, also known as common reed, is a perennial grass that can grow over 15 feet tall. It is commonly found in marsh and wetland areas where it forms dense stands that crowd out native vegetation. These monoculture that do not support the diversity needed for a thriving ecosystem Japanese knotweed is an herbaceous perennial that creates dense thickets that crowd and shade out native vegetation. In the United States rhizomes can reach 30-75 feet in length and are the chief cause of spread. Fragment of stem and rhizome can regenerate new plants. In big storm events pieces of the plant are broken off and transported to new areas, where they can establish new colonies. Finding small plant fragments digging them out and disposing of them properly can go a long way in saving resources, time, and the damage of future infestations.

Japanese knotweed is an herbaceous perennial that creates dense thickets that crowd and shade out native vegetation. In the United States rhizomes can reach 30-75 feet in length and are the chief cause of spread. Fragment of stem and rhizome can regenerate new plants. In big storm events pieces of the plant are broken off and transported to new areas, where they can establish new colonies. Finding small plant fragments digging them out and disposing of them properly can go a long way in saving resources, time, and the damage of future infestations. Multifloral Rose is an herbaceous shrub in the rose family (Rosaceae). It has canes or stems) have numerous thorns and can grow up to 15 feet in length and usually arc toward the ground and takes root, a process called layering. This creates dense thickets 6-10 feet tall. After establishment, individuals can increase their size by 1-2 feet a week during midsummer. Multifloral rose has clusters of showy, fragrant white flowers in late May or June. It spreads through seed, root sprouting, and layering. The fruit, known as rose hips, are eaten and dispersed by our feathered friends, and can persist and remain viable in the soil for up to 20 years.

Multifloral Rose is an herbaceous shrub in the rose family (Rosaceae). It has canes or stems) have numerous thorns and can grow up to 15 feet in length and usually arc toward the ground and takes root, a process called layering. This creates dense thickets 6-10 feet tall. After establishment, individuals can increase their size by 1-2 feet a week during midsummer. Multifloral rose has clusters of showy, fragrant white flowers in late May or June. It spreads through seed, root sprouting, and layering. The fruit, known as rose hips, are eaten and dispersed by our feathered friends, and can persist and remain viable in the soil for up to 20 years.