by Karen McCarthy, Newburgh Master Gardener Volunteer

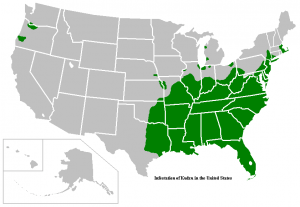

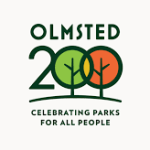

Last year, 2022, marked the 200th anniversary of the birth of the father of American landscape architecture, social reformer, and author Fredrick Law Olmsted. For Olmsted 200 events were planned by the National Association of Olmsted Parks, The Garden Clubs of America and many local garden groups. This year, the celebration continues.

Last year, 2022, marked the 200th anniversary of the birth of the father of American landscape architecture, social reformer, and author Fredrick Law Olmsted. For Olmsted 200 events were planned by the National Association of Olmsted Parks, The Garden Clubs of America and many local garden groups. This year, the celebration continues.

Olmsted was born to a family of wealthy merchants in Connecticut over 200 years ago on April 26, 1822. He had a varied work career, eventually becoming passionate about gardens after a walking tour of the British Isles in 1850. Exchanging ideas with Andrew Jackson Downing of Newburgh, New York, and his business partner, the English-born architect, Calvert Vaux was a turning point for Olmsted. At the time Downing was the foremost writer on gardening and a promoter of public parks in America. These men rejected the geometric gardens with formal, compartmentalized flower beds that conveyed the idea of man over nature. They proposed instead the English garden style that had a more natural, informal flow of plants. Rather than “conquer” they wished to “enhance” the beauty of a site. They believed that free, open public parks could be a healing space, could combat the stress of the growing industrial cities and “civilize” individuals in a new nation. Such parks would allow for healthy recreation and the quiet contemplation of nature.

Following the tragic death of Downing in 1852 in a steamship fire, Olmsted and Vaux teamed up to put these then innovative ideas into the many parks they designed, starting with Central Park in Manhattan. Ponds were dug, swamps were drained, areas were flattened for open meadows, hills were built up and boulders were exposed or moved to make everything look “natural”, as if it had always been there. Meandering pathways and carriage roads led up to views of informal gardens or groupings of trees, tying the park together. The design of plantings created an illusion of space and removed the visitor from the sights and sounds of the bustling city. When possible, trees formed a natural periphery instead of fences.

A major part of the American park concept was “communitiveness”, a term Olmsted coined, meaning that the park was to serve the needs of the community. Parks were not intended only for the rich with carriages, as so often they had been in Europe. Parks were planned as a democratic space where all society could meet and feel welcome. This “social democracy” of American parks is reflected in ”Parks for All People”, the theme of Olmsted 200.

In his lifetime Olmsted worked on some 500 commissions, including 100 parks, 200 estates and 40 academic and other institutions. Besides Central Park, Olmsted is associated with Prospect Park in Brooklyn, as well as parks in Boston, Albany, Philadelphia, Buffalo, Montreal, Louisville and so many other cities. He was also a prolific writer although he claimed not to enjoy that part of his legacy.

During the Civil War Olmsted served as the Director of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, overseeing the health and medical supplies for the Union Army. Much later in his career Olmsted worked as the site planner in the Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. His work emphasized the importance of collaboration between engineers, architects, and landscape architects.

Central Park in Manhattan, designed in 1857, was Olmsted’s first park. His last design was Downing Park in Newburgh, in 1895, also done with Calvert Vaux, Vaux’s son, Downing Vaux and Olmsted’s stepson, John Charles Olmsted. This small (35 acres) park, set on a former farm acquired by the City of Newburgh, is the only park designed for free as a memorial to Olmsted and Vaux’s acknowledged mentor, Andrew Jackson Downing. It includes all the features of Central Park in miniature: a water feature, meandering pathways and roads that lead to views of the Hudson River, hills, boulders, informal gardens and a “great lawn” for informal recreation and community events. In recent years Downing Park has been a “stand in” for Central Park in several films.

Once maintained by 30 gardeners, Downing Park now is a completely volunteer effort. The Garden Club of Orange and Dutchess Counties has been working with the Downing Park Planning Committee through a grant to restore the area of the amphitheater by trimming healthy trees and removing dying trees. A thousand daffodils were planted by adults and school children in the fall of 2021. These daffodils bloomed in time for the Olmsted 200 Celebration in Downing Park on Saturday, April 23, 2022.

The celebration continues, learn more about Olmsted and upcoming events that celebrate his legacy.

Learn More

- What’s Out There Olmsted: A Digital Guide – The Cultural Landscape Foundation

Upcoming Events

Webinars

Thursday, February 9, 2023 @ 6:00 pm

Tuesday, April 25, 2023 @ 2:00 pm

Sunday, June 4, 2023

Guided Tours and Exhibition

- Exhibition – The Thousand Faces of Mount Royal – Olmsted, the Visionary – Les amis de la montagne

- Montreal, Canada

- Open until December 31, 2023

- Guided Tour – Activism in Central Park

-

- Thursday, February 16th

- Sunday, February 19th

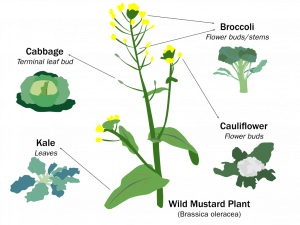

Is broccoli man-made? This was a question recently posed to me by a newcomer to the Community Garden that I frequent. I had no idea as to the correct answer, so I told the gentleman that I would have to research the topic and would share the results with him as soon as possible. What follows in this article are the results of my research.

Is broccoli man-made? This was a question recently posed to me by a newcomer to the Community Garden that I frequent. I had no idea as to the correct answer, so I told the gentleman that I would have to research the topic and would share the results with him as soon as possible. What follows in this article are the results of my research.

Many of the vegetables included in the

Many of the vegetables included in the