Mobile phone patents and game theory

[Article http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2011/08/16/quest-for-patents-brings-new-focus-in-tech-deals/]

The article above gives a summary of the recent actions of Google, Apple, and Microsoft to buy thousands of mobile phone patents. It makes it clear that bankers and corporate executives are amazed that patents, which were “barely footnotes to deals a decade ago and rarely figured in the valuation of companies” are now suddenly selling for billions of dollars. For instance, the article cites the sale of Nortel’s 6,500 patent collection, which was originally valued at 700 million dollars, for an incredible 4.5 billion dollars. Similarly, the article points out that Google’s recent acquisition of Motorola Mobility for 12.5 billion dollars was done primarily for the patents and not for the actual cellphone business.

Was this shift in the tech world truly as surprising and unexpected as these bankers and executives seem to think? I will use a bit of game theory to find out.

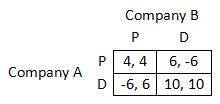

First we consider the game that mobile phone makers played a decade ago. At the beginning of each financial quarter, each company must decide if they want to invest all of their capital in phone development (strategy D) or if they want split their capital between patent purchases and phone development (strategy P). It is reasonable to assume that if both companies choose to play the same strategy that they won’t attempt to sue each other because their patent collections will be more or less equal. Furthermore, if they both choose strategy D they will make more money than if they both choose strategy simply because they have invested more in making and marketing products. If they choose different strategies, the company that picked P will take the other company to court and win. But, as the article states, in the past it was difficult to win a patent case so the payoff for the suing company will be less than if they had put all of their capital in phone development. Picking some reasonable numbers that fit these assumptions, we get the following game with values in millions of dollars profit:

This game has two pure Nash equilibria at (D, D) and (P, P). Furthermore, we would expect this game to reach the (D, D) equilibrium more often than the (P, P) equilibrium because (D, D) gives higher profits for both companies. This matches the past behavior of phone makers presented in the article.

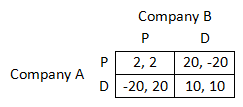

The article explains that beginning in the early 2000’s suing for patent violations gradually became easier and more profitable. At the same time selling price of patents began to rise as well. Taking this into consideration, we get a new game for mobile phone makers today:

Comparing this game to the old game, we see that the (P, P) Nash equilibrium still exists. However, there is no longer a Nash equilibrium at (D, D) because it is now more profitable to buy patents and take your competitor to court than it is to simply invest in phone development. We can now see that the “tipping point” was when it became equally profitable to sue as it was to put all capital in phone development; after this condition was met it was inevitable that both companies would end put playing strategy P. Perhaps if the bankers and executives had run this game as a “what if” scenario, they would have predicted this patent craze years ago.

[…] is the original post: Mobile phone patents and game theory | Networks Posted in Apple, Phones Tags: apple, article-above, buy-thousands, google, makes-it-clear, […]