The county’s Master Gardener Volunteers and several others with an interest in foraging wild plants recently met at a local trail to learn from Tusha Yakovleva. Tusha brings a lifetime of learning about local plants to her educational events, from her childhood in Russia and Scotland to her time spent exploring ethnobotany with native youth in the Adirondacks.

She started by guiding the group to use all of our senses when learning about a new plant. Though we used a plant known to most of us for this exercise, rather than skipping right to how it looks and what it’s called, we started with feeling the presence of the plant, noticing the sounds in the plant’s environment, the hairiness of the stem, the smell of the crushed leaves. We even considered what name we might give the plant based on our observations. Lastly, we landed on the common name, goldenrod, and its use as an immunity boosting tea. This guided exercise primed us for what Tusha called “slow and present observation” throughout our 2+ hour walk on St. Lawrence University’s Kipp trail.

Of the many plants we encountered, some I most enjoyed learning about (and tasting) included black locust flowers – which taste like alfalfa sprouts – and wood nettle, our native nettle with tasty leaves that can be dried for tea, eaten raw or cooked, or even dried and rehydrated.

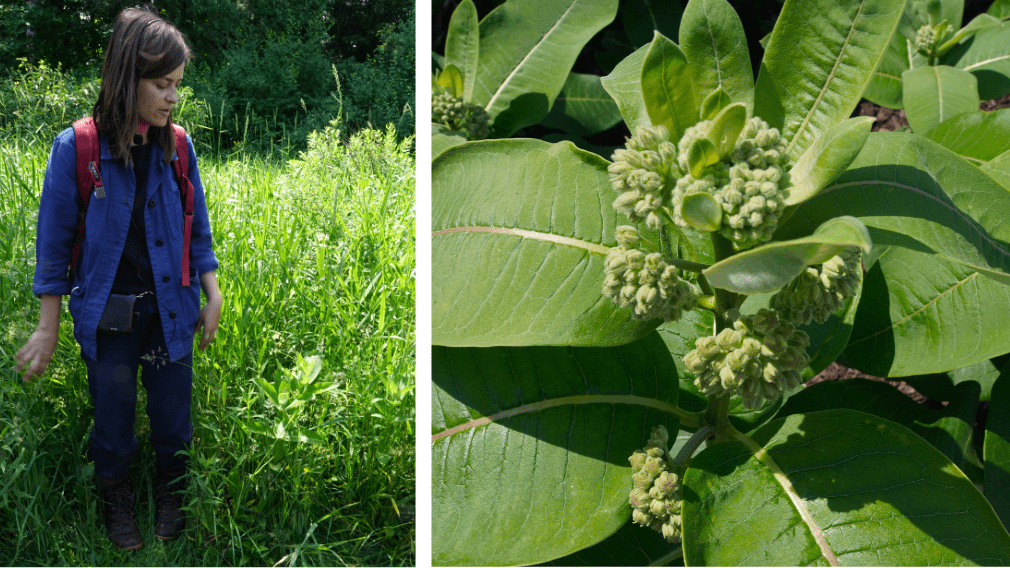

I also tried the broccoli-like unopened flower buds of common milkweed – the only nontoxic species of milkweed. In addition to the flower buds, the young shoots are edible before the leaves unfurl in spring, and the aromatic flowers can be used to flavor drinks and baked goods.

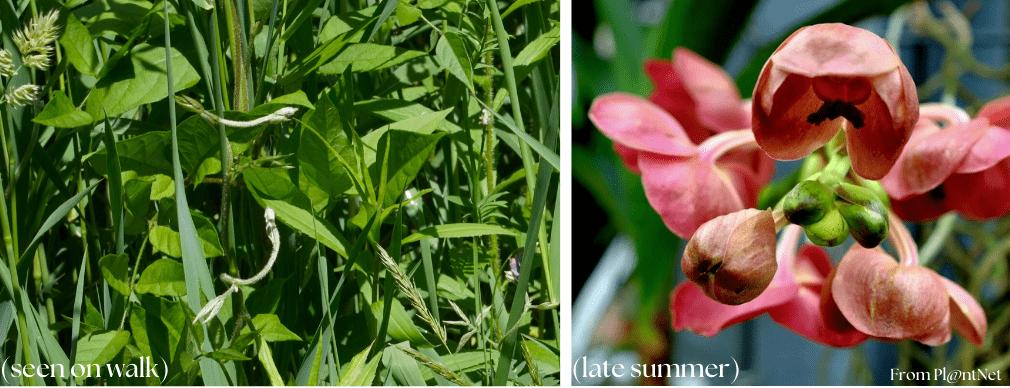

The prickly ash (Zanthoxylum americanum) Tusha led us to was a treat. Our only native citrus, prickly ash’s fragrant leaves can be used for seasoning in place of lemongrass in cooking or drinks. Local forager, Sara Lynch, added that the small late summer fruit of the prickly ash, known as “Szechuan peppercorns,” are prized for their intense flavor and slight numbing quality. They’ve been described as “mind blowing and mouth numbing.”

Tusha’s passion for the cultural significance of plants was clear when she described the role of birch trees in her native Russia and other “circumboreal” places that are linked by birch species. She grew up learning the four primary ways birch is used – “for lighting, healing, cleansing, and quieting.” The birch provides dry tinder and clean fuel, medicine for a myriad of ailments, brooms and twigs used in banya ritual, and as a natural lubricant.

Nearby, we found some American groundnut, a native perennial vine in the legume family. It has complex, magenta flowers and, later, edible fruits and large edible tubers dubbed “potatoes on a string.”

Tusha also informed us about those plants we should not consume. The toxic plants we came across on our walk included water hemlock, false hellebore, and doll’s eyes (baneberry).

Toward the end of our walk, Tusha spoke about careful and sustainable harvesting practices. She described the nuances of this issue, since there are “wild edibles,” like invasive garlic mustard, that we should harvest as much as possible to slow their spread. At the other extreme, there are rare native plants that can take many years to reach maturity, plants we should be content to visit without consuming. Tusha cautioned us against “stepping too quickly into extractive relationships with plants,” describing the 5-7 years needed for wild leeks (ramps) to produce seed, and the myrmecochory they depend upon for dispersing them.

We have time and awareness to consider whether the way we are engaging with plants is positive, neutral, or negative when we are able to move slowly with full presence, and not only think of our own well-being, but also the land’s. Tusha went on to describe varying levels of positive impacts we can all participate in: picking up trash, encouraging native plants, and supporting native land sovereignty.

This was a memorable in-service for our Master Gardener Volunteers whose ongoing curiosity and generosity keeps them learning and sharing with the public. As one of them said, “I was bowled over and amazed by Tusha’s expansive knowledge and personal experiences with so many wild edible plants.”

Tusha serves as Community Outreach Coordinator for the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment at SUNY ESF, and is the founder of Found With.

Erica LaFountain is Community Horticulture Educator for St. Lawrence County. She has a background in organic vegetable farming, gardening, and orcharding and has a homestead in Potsdam, NY.