By Dorothea Anna Ganetsos

History of Educational Equity

Equality in terms of access to a quality education is a topic that has been on the forefront of political debates ever since the famous 1954 Civil Rights trial Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka. In this Supreme Court hearing, our federal government attempted to establish a nationwide model that promoted the educational inclusion of all children, regardless of their race or socio-economic standing (Baum 2008). While this early governmental intervention was a promising start towards creating an equitable school system, a lack of monetary funds and governmental guidelines have permitted socio-economic discrimination in education to continue. The effects of this faulty system are most strongly felt by children in urban or rural areas, of low income families, and of minority descent.

Despite the good intentions behind this ruling, the federal government failed to impose a mechanism through which schools should easily be desegregated, resulting in the continuance of unequal educational treatment for numerous minority citizens- especially in Southern states- for about fifteen years after the Brown vs. Board trial. The explicit segregation of our nation’s educational system was finally put to a halt in 1968 with court hearings such as Green vs. New Kent County, Virginia and Keyes v. Denver School District, which forced the federal government to step in once more with court mandates and the direct monitoring of these school districts in order to ensure that every child had the opportunity to enroll in the same institutions as their Caucasian counterparts(Baum 2008).

Inequality Due to Monetary Constraints

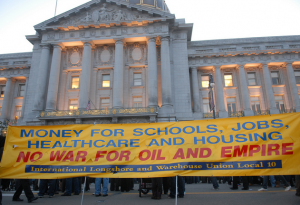

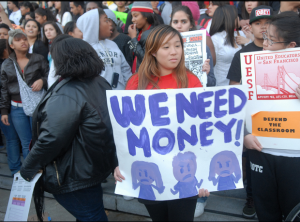

Minority Students Lamenting the Lack of Educational Funds

San Francisco Bay Area Students “Source: Ko Ko Lay on Flickr”

In a 1973 landmark case, San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, the United States Supreme Court ruled that education was not a constitutional right (Walker 2013). This trial was brought about low income parents who were unhappy with the unequal educational treatment their children were receiving compared to those of more prosperous families. This trial makes it evident that not every minor has the same educational options and resources available to him or her. According to Senator Edward M. Kennedy, despite numerous citizen pleas for social progress in the educational system, our schools are “still being financed by a system rooted in the 19th century”(Congress 2002). Essentially, this means that less than 2% of our federal budget is dedicated to funding the education of children from grades K to 12, which accounts approximately 9% of the necessary funds for each state’s school systems(Congress 2002). It is up to each individual state to come up with the remainder of the money needed to run these educational institutions.

Congressional Session Similar to the ones in which the Future of America’s Educational System is Discussed

Source: Teaparty.org

This lack of monetary funds has serious implications for the states, school districts, and American students. Although there is a federal law in place that states resources must be distributed evenly for each school within a school district, there is no such law mandating the even allocation of funds to districts from the state governments. This financial structure results in states relying on local district financing for the bulk of their educational revenues, a process which clearly favors the wealthier areas that generate more money from taxes on larger houses, increased spending, etc; leaving poorer families in less affluent areas with worse resources and educational facilities.

Positive Feedback Loop Created by Monetary Constraints

Clearly, the first major implication of our nation’s framework for financing schools is a lack of money for schools in low income areas; specifically schools educating minority children and those living in inner cities or rural areas. These schools are unable to attract experienced teachers and can only afford to pay new ones despite the fact that disadvantaged schools have the greatest need for quality educators. This trend is exemplified by the fact that low income students in the city of Chicago are 23 times more likely to have a teacher who has failed all five of the basic skills tests of the Illinois teacher’s exam. In New York City, 20% (13,000) of all teachers are not certified or fully qualified under New York state law, all of which are assigned to the worst performing schools. In Philadelphia, this number is increased to 50%(Congress 2002).

Unfortunately for these students, the federal government bases educational progress on the AP courses offered and taken at a school, SAT and ACT scores of students, drop out and school-completion rates, and job placement and retention rates(Perry 2010). If a district, whose budget is determined by the state based on its wealth, performs poorly with regards to these standards, the federal government can choose to withhold funds from them- forcing them to either miraculously better their academic performance or shut down. On top of all of this, after our government enacted the No Child Left Behind Act in 2001, which set extremely high standards for elementary achievement, they proceeded to take away $4 billion from low income public schools and put this money towards private school vouchers(Congress). Without a qualified teacher, whiteboards, textbooks and much more, it is extremely difficult to incentivize disadvantaged minors to academically excel when they can clearly see that their government does not value their education or provide them with the basic amenities that their wealthy counterparts take for granted.

Policy Recommendations to Alter this Problem

According to the Alliance for Excellence in Education, if African Americans and Hispanic Americans received the same educational opportunities and went to college at the same rate as whites our GDP would increase by $231 billion and generate $80 billion more in tax revenues- demonstrating the tremendous amount of economic potential that our nation is neglecting due to inefficient planning and shortsighted agendas(Perry 2010). The global Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development maintains that there are two key dimensions of equity in education: fairness and inclusion(OECD 2008). In order to achieve these, the government needs to direct limited education resources to poorer students and regions to ensure minimum educational standards are being met everywhere instead of punishing schools that lack money for failing to perform. Similarly, contrary to our country’s current approach, test results should not determine the amount of funding an area receives. Rather, we should support schools with weaker results, and use these standardized tests to bring schools up as opposed to allowing them to polarize school quality.

If our society puts more time and consideration into the issue of inequality in the educational system, we will find ourselves more prosperous, informed, efficient, and understanding. Our country currently ranks at the very bottom of industrialized nations in terms of educational opportunity for affluent versus poor family, an unacceptable trend for a nation that boasts its superiority and progress. We must strive to reduce this inequality gap by creating a more adequate funding system through which the disadvantaged are not further punished for their lack of wealth, the location of their residence, or the ethnic background. Once every child has an equal access to educational opportunity and the same likelihood for success will we be able to call ourselves a truly equitable nation.

Works Cited

Baum- Snow, Nathaniel. School desegregation, school choice and changes in residential location patterns by race. Washington, DC: Division of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs, Federal Reserve Board, 2008.

Congress. Senate. America’s schools: providing equal opportunity or still separate and unequal? hearing before the Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, United States Senate, One

Hundred Seventh Congress, second session, on examining educational equity and resource adequacy among public school systems within and among states, May 23, 2002. Washington:Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, 2002.

Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. “Ten Steps for Equity in Education.” Policy Brief (2008).

Perry, Emma. “The Social Class Gap for Educational Achievement: A Review of the Literature.” RSA Projects (2010).

Walker, T “More School Districts Suing States For

Education Funding” NeaToday. http://neatoday.org/2013/02/04/more-school-districtssuing-states-for-education-funding/(accessed November 13, 2013).