By Peter Duba

Chicago recently shut down 50 of its schools in the largest single wave of public school closures in history (Irvine, 2012, p.1). What was especially damaging about these school closures was that more than 90 percent of the schools shuttered were found in predominantly poor minority neighborhoods (p.1). For a city that has been struggling in recent years to alleviate rampant inequality this action further exacerbated a problem that has been generations in the making. The question is though, how did the city get to this point, and why, with new positive developments in its urban prospects, are problems of education inequality and systematic segregation still prevalent?

The first question is easy to answer. Like many problems in contemporary cities, the roots of Chicago’s school problem can be traced back to the latter half of the 20th century. Suburbanization and white flight decimated city tax incomes and left a city that was built to accommodate 4 million residents serving a much reduced population of 3 million. The announcement came as board members of the Chicago Board of Education “charged that some city schools were being “underutilized” and should consolidate to save resources” (2012, p.1).

The second question however, poses more of a challenge. In the news recently, there has been much attention paid to the comeback of many post-industrial cities. This trend is made evident in the growing populations of rust-belt cities and in the increasing number of smart educated professionals moving back into cities. However, in light of such positive growth, why do many cities continue to struggle to keep schools in minority neighborhoods on par with the schools in the newly revitalized and gentrified neighborhoods? The answer can be found in several places. The first driver is the motivation that cities have to keep these new well off and well educated residents in the city. Many times once these individuals have children, they leave the city and move to the suburbs looking for schools that they presume to be of better quality for their children. The cities’ strategy for interrupting this pattern through creative taxation is the second driver of this inequality. Cities have tried addressing this suburban flight problem with a highly controversial tax financing tool called “tax capture districts”. In essence, special taxes are levied and held (or ‘captured’) in the immediate, often more wealthy neighborhoods around the new schools, ensuring that the tax dollars are not distributed equally throughout the city (PCAPS, 2013, P.7). Herein lay the final driver for the inequality. The ‘tax capture district’ strategy was originally meant to capture the taxes of downtown big business, (an area where many of the residents live) but instead, it often sequesters tax money from the underperforming minority districts, reinvesting it instead in the up and coming inner city neighborhoods. Philadelphia provides an example of the complexities of school and city finance. Philadelphia recently created a special school program to develop schools that cater to the young families who have recently moved into newly gentrified neighborhoods. These new schools, while successful in keeping families in the city, did little to address the problems of systematic racial inequality. Because, in order to keep the inner city schools running at the level that was required to maintain an education comparable to the suburbs, Philadelphia had to capture and hold the tax revenue from within the limits of the individual school districts, keeping the tax revenue in the neighborhood for funding the local neighborhood school, further widening the education gap (p. 3).

Effectively the city is just a growth machine for inequality (Molotch, 2001, p.312) . As cities keep siphoning funds from underperforming minority neighborhoods to improve wealthy neighborhoods the schisms keeps widening. Another continuing problem that plagues minority school districts is the continuation of reform efforts undertaken by white administrators in the 1960s. In the article “Race, Social Class, Educational Reform,” author Jean Ayon explains what happened when members of the Board of Education, a union representative, and a parent representative for the Newark school district had held a strategic reform session together in June of 2003 to decide which projects should be attempted. Although most representatives attending the meeting were African American attempting to develop creative and innovative strategies for bridging the gap between underperforming Newark schools and successful suburban schools, they “chose the exact same things” that had previously been previously done, staying with the conventional wisdom and approaches that had led to the current situation (2003, p.77). In the end, it came down to what would be politically do-able. Ayon explains that “education is as much about politics as it is about kids. You have to be aware of the larger bureaucratic system you’re working in. The old-boy network, they’re white men, and that’s where the money is! You have to go to them for money to do things. What you do has to be acceptable to them” (p. 80).

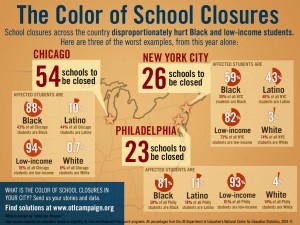

This info-graphic reveals the true nature of school closures in the inner-city. (www.blogs.edweek.org)

This systematic inequality further drives inner-city schools to underperform, hemorrhage children and funding, and eventually be shut down. Another problem that leads to further division is resignment. Many inner-city school leaders and personnel “appear resigned to the failure of current reform” and have little hope of finding support from outside sources (P.82). A major consequence from this loss of hope is that school officials find that it is “harder to garner support for projects that most people are convinced will fail” (p.82) Without the support of a community, the enthusiasm of reformers, and the expectation of change, many schools simply fall into a business as usual mindset furthering the decline of the inner city minority schools. For those who claim that it is not simply minority schools that are falling into decline but rather inner-city schools as a whole, I say look no further than the map below detailing the location of schools that Chicago is closing.

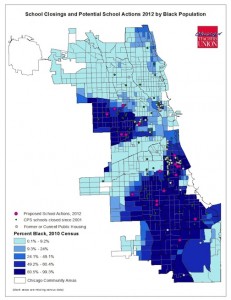

Chicago’s massive school closure program affects primarily minority neighborhoods. (http://www.ctunet.com/)

Much as discussed above, in an effort to keep the middle class, majority culture in the city, Chicago, when attempting to close a billion dollar shortfall, kept schools in white neighborhoods while schools in predominantly African American neighborhoods were closed. The city’s approach only furthers the achievement gap between white children and black children.

It is clear that education policy in urban areas only stands to promote systematic inequality that, as time has passed, has become cyclical. The wealthy consume more of the school budget as the poor receive a smaller share. The disinvestment only leads to discouragement which leads to more decline and more disinvestment.

Sources:

- Anyon, Jean. “Race, Social Class, and Educational Reform in an Inner-city School.” Teachers College Record 97.1 (n.d.): n. 1995. Print.

- Irvine, Martha. “Chicago School Closings.” Huffington Post. N.p., 9 Dec. 2012. Web.

- Molotch, Harvey. “The City as a Growth Machine.” Readings in Urban Theory. London: Routledge, 2001. N. pag. Print.

- PCAPS. Short-Changing Philadelphia Students: How The 10-Year Tax Abatement Underwrites Luxury Developments And Starves Schools. Philedelphia: n.p., 2013. Print.

- Porter, Michael E. The Competitive Advantage of the Inner City. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School, 1994. Print.

- Chicago Board of Education. “Press Release.” Chicago Public Schools : CPS Announces Five-Year Moratorium on Facility Closures Starting in Fall 2013. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Dec. 2013.